LET ME MEND YOUR BROKEN BONES

2024

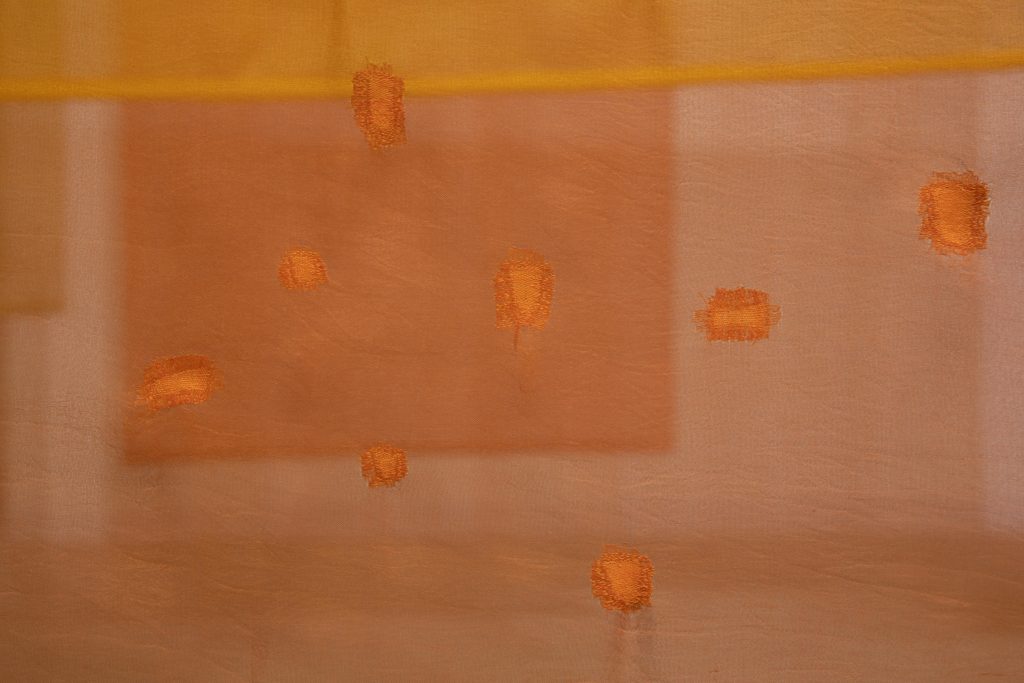

The artwork portrays a delicate memorial to the loss of historical heritage sites in Palestine, continuing Awartani’s ongoing body of work documenting cultural destruction in the Arab world caused by war and colonialism. This iteration brings to light the devastating effects on UNESCO heritage sites as one of the consequences of the Gaza Genocide, which include the Great Omari Mosque, the Church of St. Porphyrius, Anthedon Harbour, and Hamam Al Samra. These ancient sites—some dating back to the Middle Ages, with Anthedon Harbour tracing its origins to the Iron Age—witnessed several empires such as the Byzantine, Mamluk, Ayyubid, and Ottoman empire. They have now been completely destroyed by Israeli Occupation Forces.

To create these pieces, Awartani studied documentation of the ruins, translating the devastation into silk panels with carefully darned tears that evoke the holes and rubble of these historic structures. The mending process reflects a yearning for a future where repair and restoration are possible. Awartani continues her collaboration with master artisans in Kerala, who dye the silk with medicinal herbs—materials that themselves bear witness to a regional history of colonialism. This work serves as a poetic, spiritual, and emotional attempt to address long-standing wounds, offering a meditative act of remembrance and repair.

Installation shot of Let Me Mend Your Broken Bones, 2024, Medicinally-dyed and hand-embroidered silk, installation, 261 cm x 290 cm (8 pieces, 129.65 cm x 70.2 cm each), Courtesy of the artist. Commissioned by Manifesta 15 Barcelona Metropolitana

STANDING BY THE RUINS II

2024

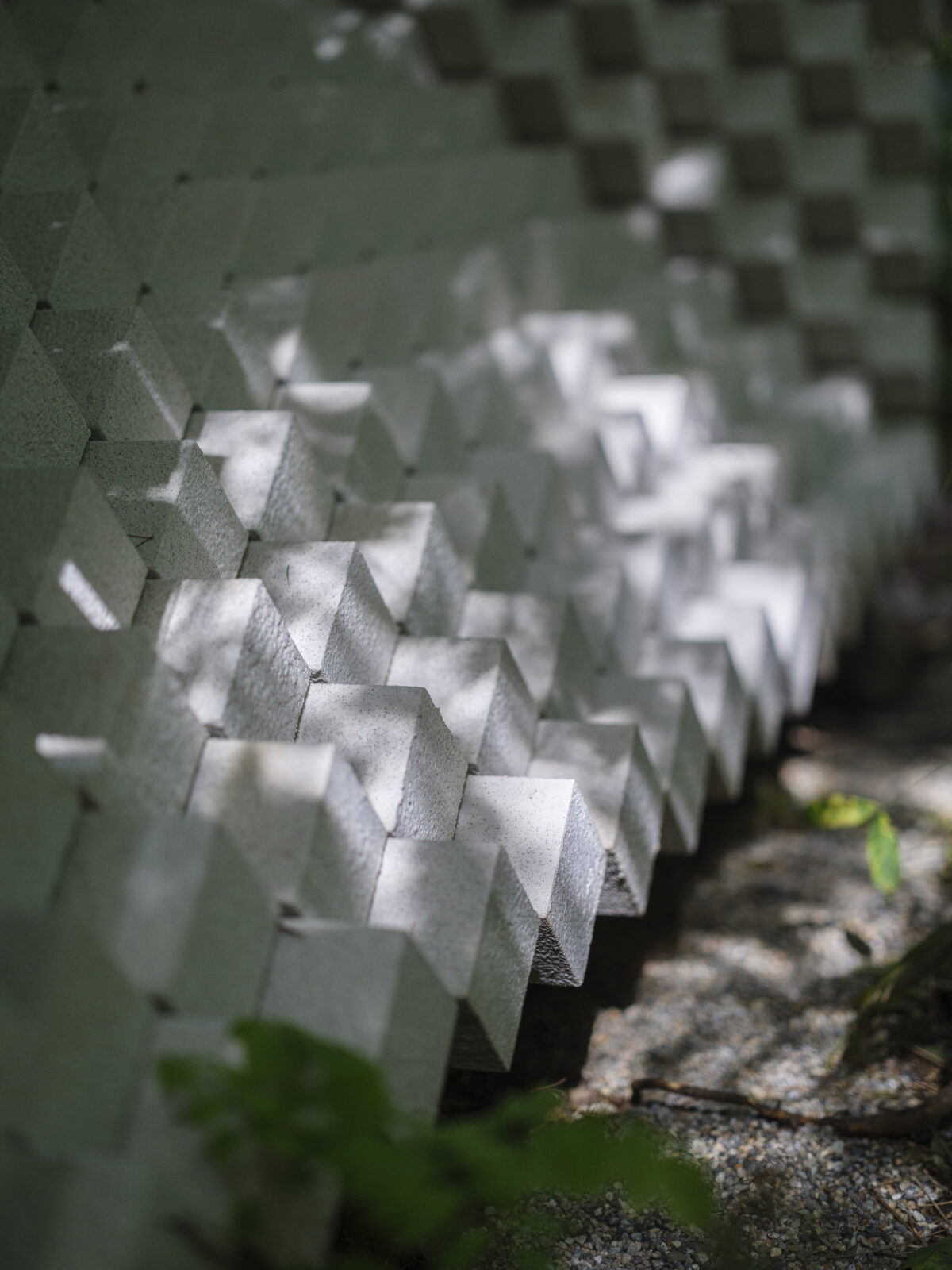

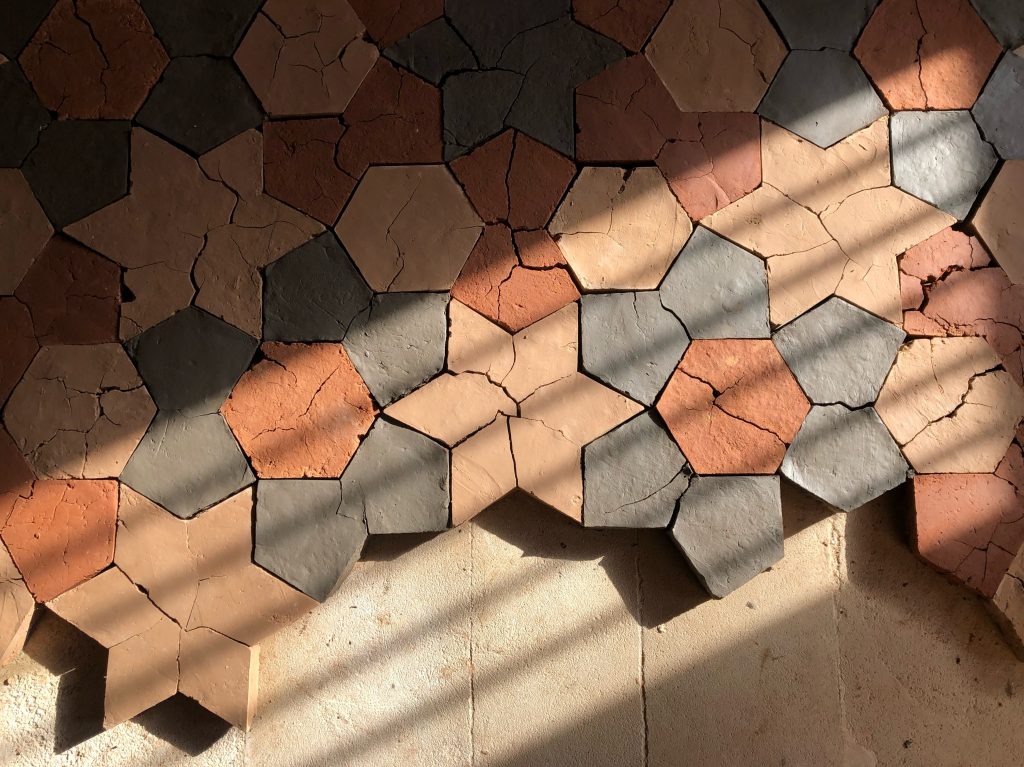

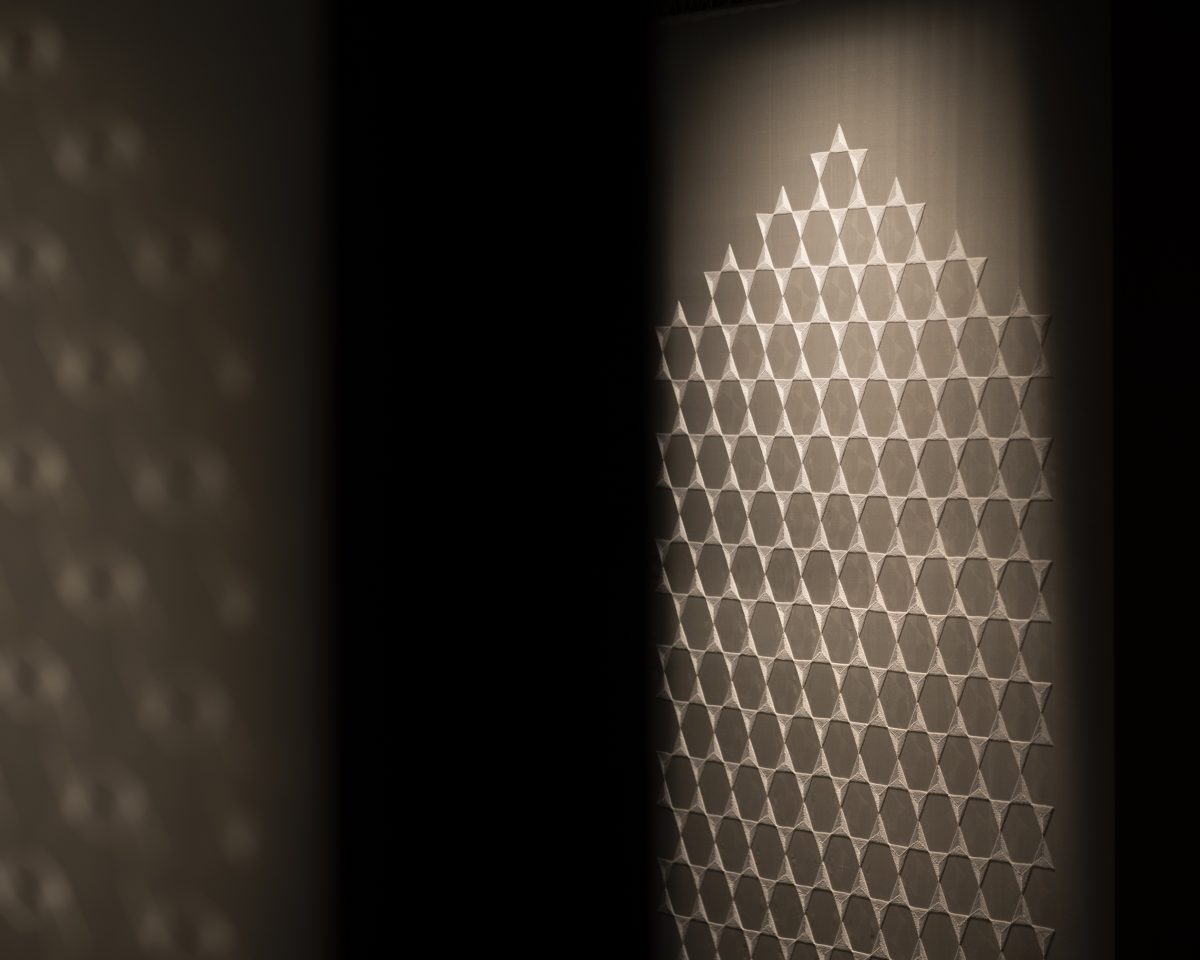

Standing by the Ruins is a title borrowed from an early pre-Islamic poetic form: wuquf ‘ala al-atlal, known as “ruin poetry”. This motif is believed to have originated in the 6th century, with Imru’ al-Qais, the last king of the Kindite kingdom in the Arabian Peninsula, who lived in exile. Considered one of the greatest figures of Arabic literature, his most famous poem describes a character longing for his beloved while looking at a devastated campsite. With this, he became the precursor of a style that is still relevant today, a genre that reflects on love and loss, on destruction and the passage of time, through the lens of abandoned, destroyed or vanishing places. Awartani’s central installation in the exhibition gives ruin poetry a physical body: a melancholic visual requiem, the work comprises around 730 clay bricks assembled to look like traditional patterned flooring at first glance. In reality, they replicate the geometric designs adorning the outside walls of Qasr Al Basha palace, one of Gaza’s most significant landmarks. Dating back to the mid-13th century, the building carries typical elements from Mamluk and Ottoman architecture and sustained heavy damage in the past year due to the Israeli bombardment on Gaza. Collaborating with artisans in Saudi Arabia, Awartani creates these bricks using ancient earthen construction techniques, but intentionally omits a crucial binding agent, allowing the patterned blocks to crack and deteriorate as they dry. In her attempt to retain traces of both disappearing architecture and intangible heritage, the artist mirrors the vulnerability of the original structure and brings to light a slowly fading craftsmanship.

Installation shot of Standing by the Ruins II at Sfeir-Semler Gallery in Hamburg 2024. Compressed earth, 450 cm x 1130 cm x 4 cm. Images courtesy of the Artist and Sfeir-Semler Gallery Beirut/Hamburg

WHEN OUR PATHS COLLIDE

2024

This sculpture draws inspiration from the salt trade history of Omachi City. With no rock salt as a natural resource in Japan, salt could only be harvested from the shores of the Sea of Japan, which was then transported inland from the coastal areas. These transport routes were commonly known as “Salt Roads” and one of these historic routes ran through Omachi City, which was ancient enough to be mythologized in the “Kojiki” – an early chronicle of Japanese myths. Drawing from this history, Awartani’s artwork takes the form of a geometric sculpture that is nestled within the landscape of Omachi’s forests. Made from locally sourced materials, the cubic shape of the artwork takes inspiration from the geometry of salt crystals which are crystalline structures that form, when salt does not have any impurities, through ionic bonding of sodium and chloride. This natural phenomenon is commonly found on the shores of the Dead Sea in Jordan and Palestine where the artist is from. The artwork pays homage to the shared history of salt as well as the important role it played in the development of Omachi City. As a commodity it had an immeasurable impact on the development of the human civilization, it was a valuable commodity throughout history and has played a role in society and economics, wars, and trade routes, and even language and literature. Cities, states, kingdoms, and empires have risen and fallen, because of it.

Installation shot of When Our Paths Collide at the Northern Alps Festival 2024. Pine wood, paint, 275 cm x 275 cm x 275 cm. Images courtesy of the Artist and Northern Alps Festival

COME, LET ME HEAL YOUR WOUNDS. LET ME MEND YOUR BROKEN BONES

2024

Awartani’s installation Come, let me heal your wounds. Let me mend your broken bones, is a requiem for the historical and cultural sites that have been destroyed in the Arab world during wars and by acts of terror. Chillingly, the installation expands with each iteration to make room for newer documentation. This edition adds testimony to the devastation in Gaza and the sites that have been flattened indiscriminately through bombings and bulldozers, along side seven other Arab nations – Saudi Arabia, Syria, Tunisia, Libya, Iraq, Egypt and Yemen.

Awartani tears nearly 400 holes across yards of silk, each rip marking a heritage site that has faced acts off terror and destruction. Then she darns—a fading practice far more intimate than patchwork but no longer valued—each gash tenderly as a gesture for healing; the scars a representation of the physical and emotional ones left behind in the real world. The fabric is dipped in around 50 herb- and spice-based natural dyes that carry medicinal value, utilising the sacred healing properties embedded in traditional textile dyeing practices of Kerala, which Awartani spent time learning.

There is no geographic correspondence to each panel; rather, together they are borderless representation of annihilated cultural heritage. In the face of ongoing destruction as well as polluting effects of big industries, the work is both a plea to safeguard ancient civilisation in the Arab world as well as a bid to recall and rejoice in the collective history of artisanship, the knowledge of healing plants, and the venerable tradition of repairing and revering objects.

The artist’s participation was supported by the Diriyah Biennial Foundation.

Come, let me heal your wounds. Let me mend your broken bones, 2024, Darning on medicinally dyed silk, H 520 x W 1250 x D 297, ) © Dana Awartani, Photography by Venice Documentation Project.

LET ME MEND YOUR BROKEN BONES

2023 – Present

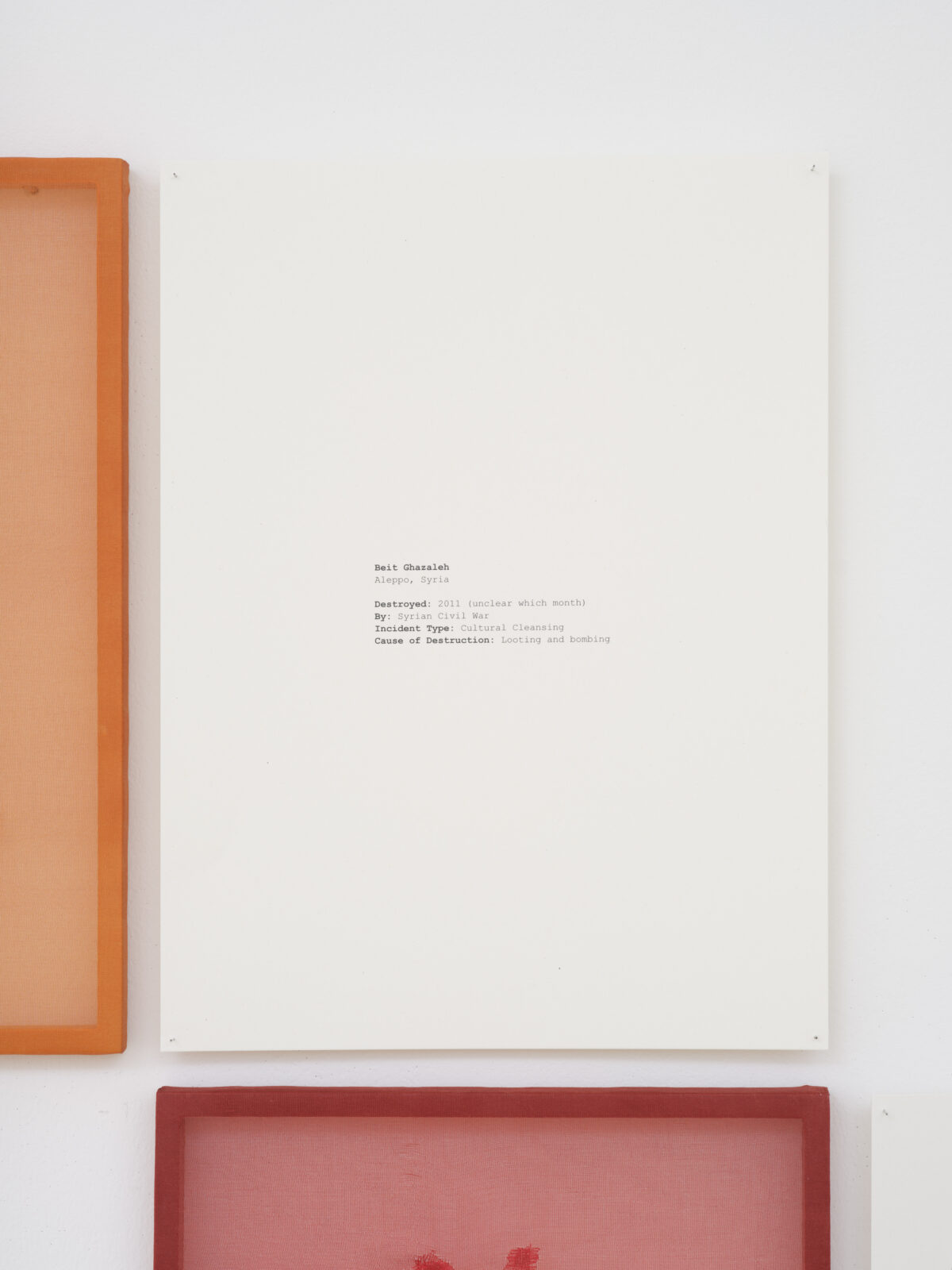

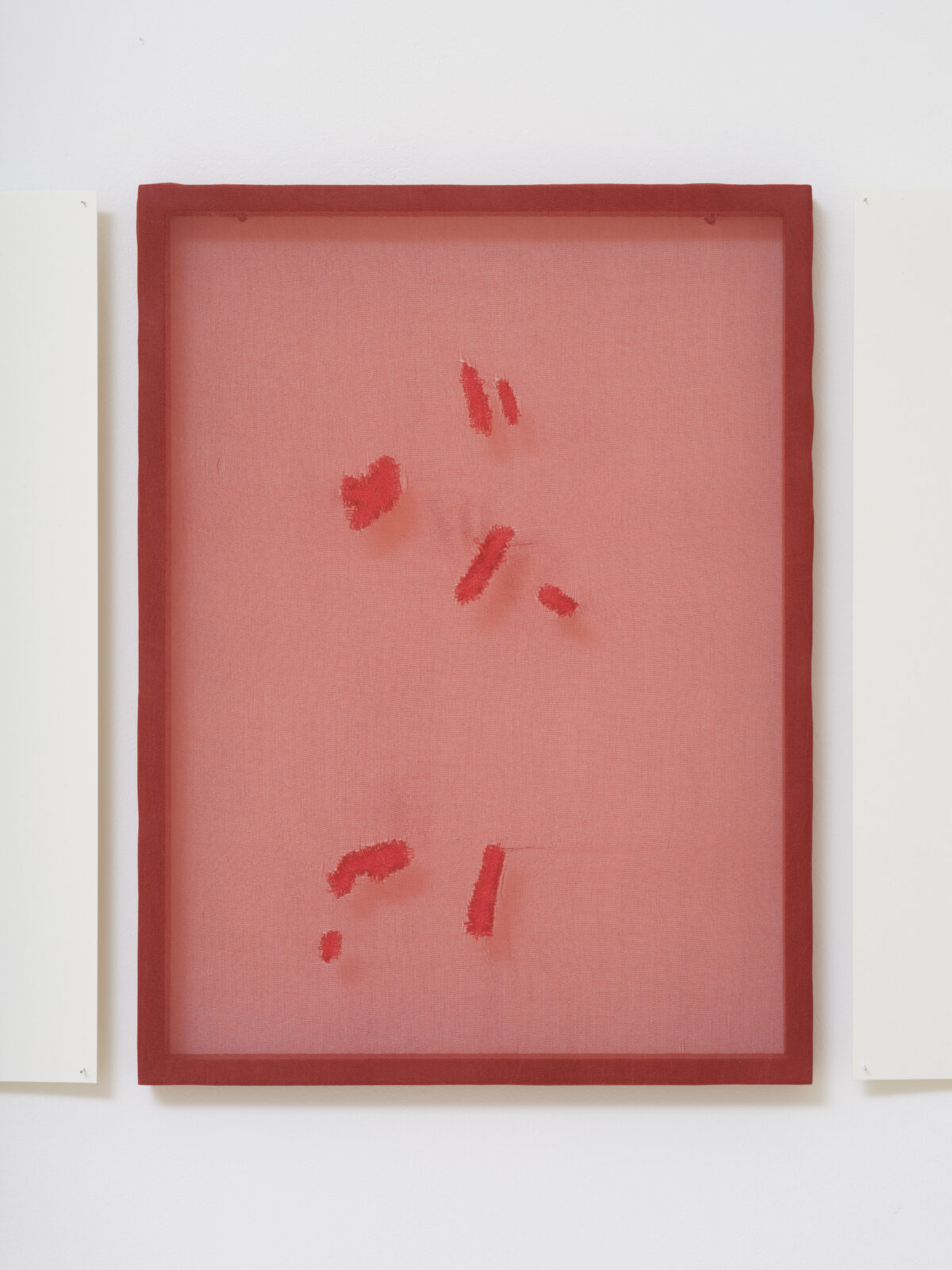

In her latest work, Dana Awartani meditates on themes of sustainability and cultural destruction. The work is composed of naturally dyed silk fabrics, handmade in Kerala, which have been stretched onto frames and displayed in a serial manner along the gallery’s walls. The fabrics are saturated with a multitude of natural herbs and spices that have specific medicinal functions in South Asian and Arab cultures. Awartani’s material choices speak to the work’s ethical and ecological terms of production, and further embody acts of resistance against mental and technological colonial violence given the dual emphasis on artisanal production and indigenous medicinal knowledges.

Awartani also creates tears and holes in the textiles, which correspond to the silhouettes of physical violence enacted on buildings in Arab nations at the hands of Islamic fundamentalists. Sourced from the The Antiquities Coalition (an organisation that catalogues and protects these vulnerable heritage sites), the accompanying texts for each panel list the exact location and time of these traumatic events, as well as the cause and the group claiming responsibility. Mending these punctures through a process of darning, tracing the holes or rubble with thread, Awartani’s work metaphorises possibilities of collective healing while recalling a venerable tradition of repairing and revering objects.

Let me mend your broken bones I, 2023, darning on medicinally dyed silk and paper, 16 pieces (27 cm x 36 cm each). © Dana Awartani, Images courtesy of Lisson Gallery.

WHEN THE DUST OF CONFLICT SETTLES

2023

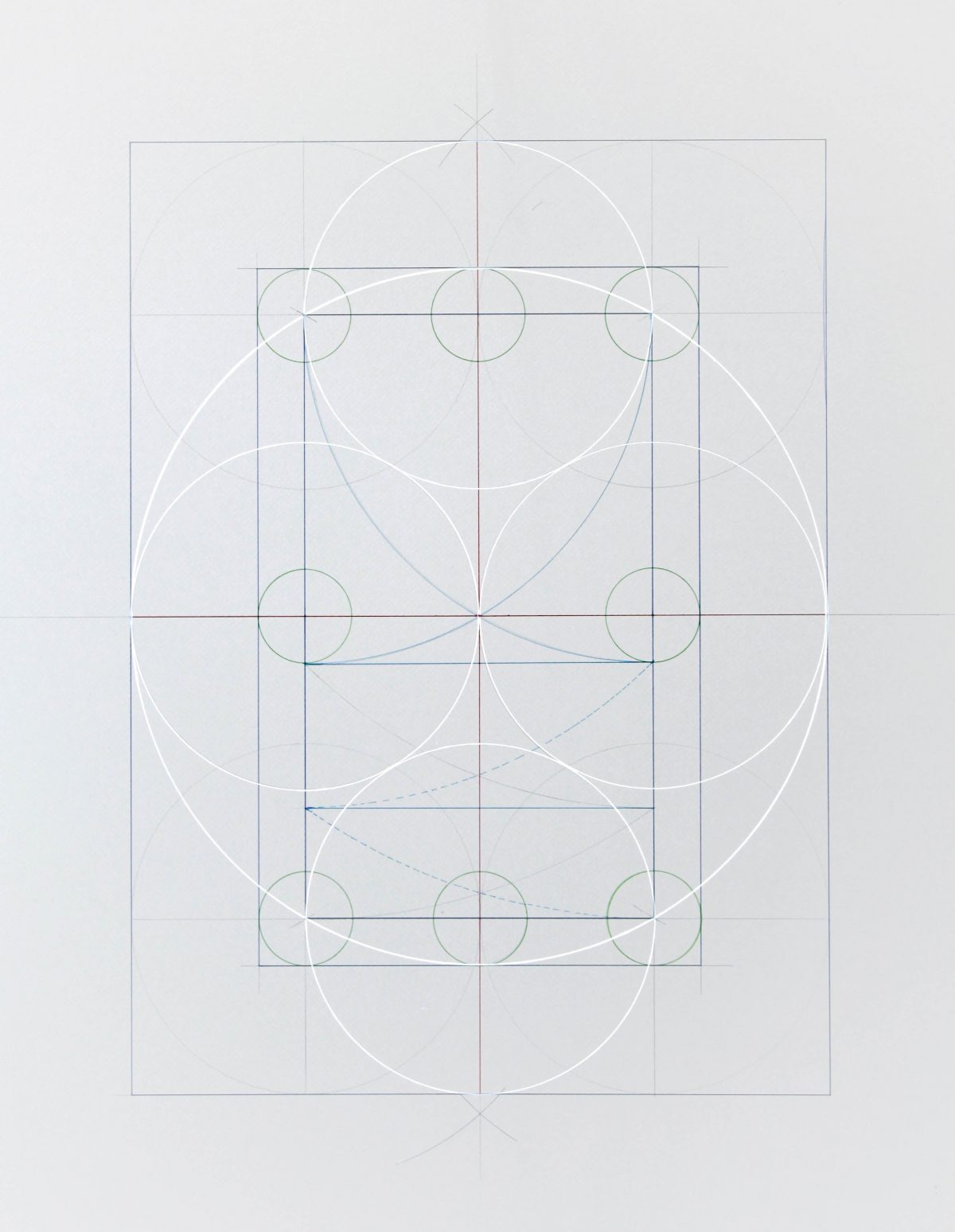

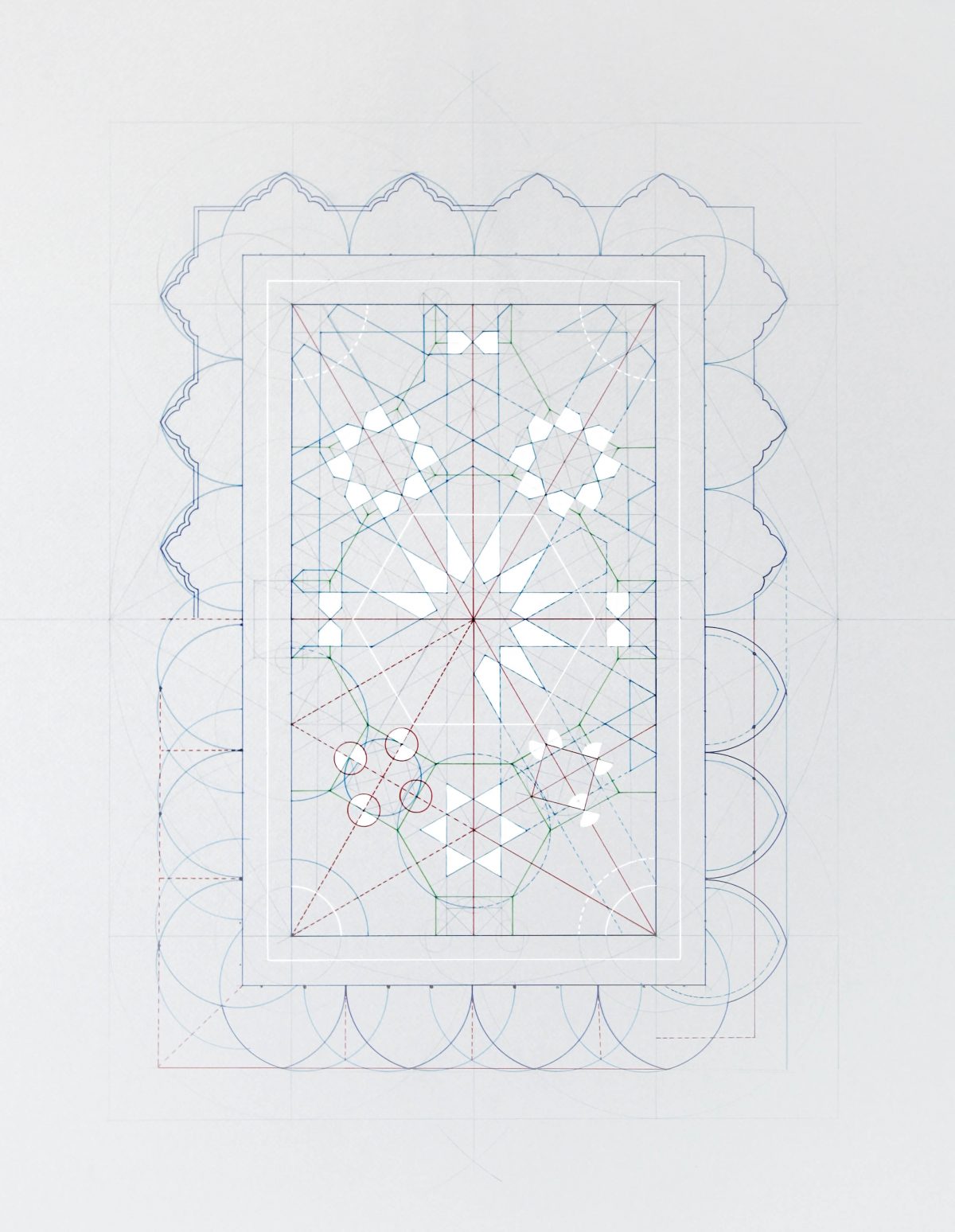

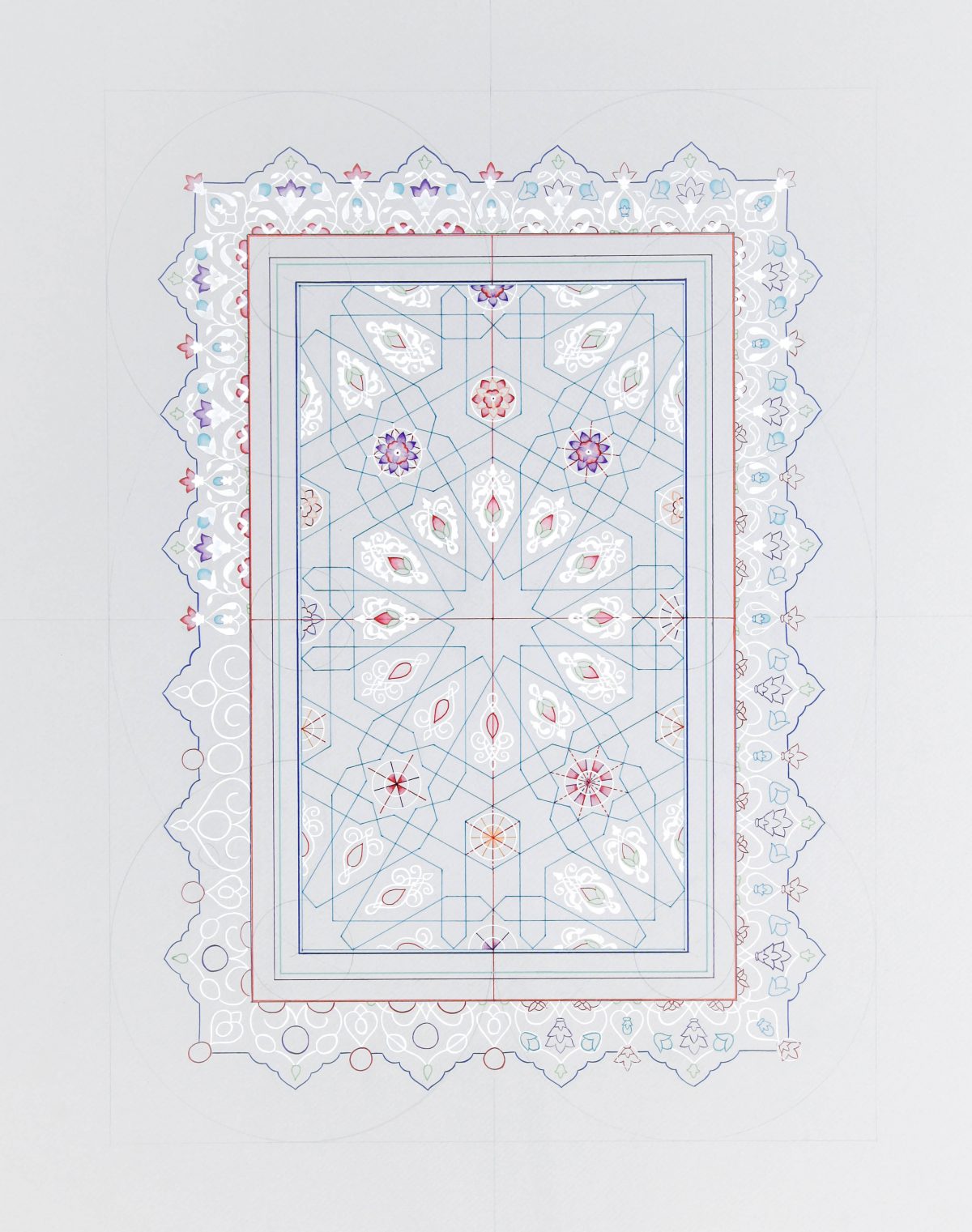

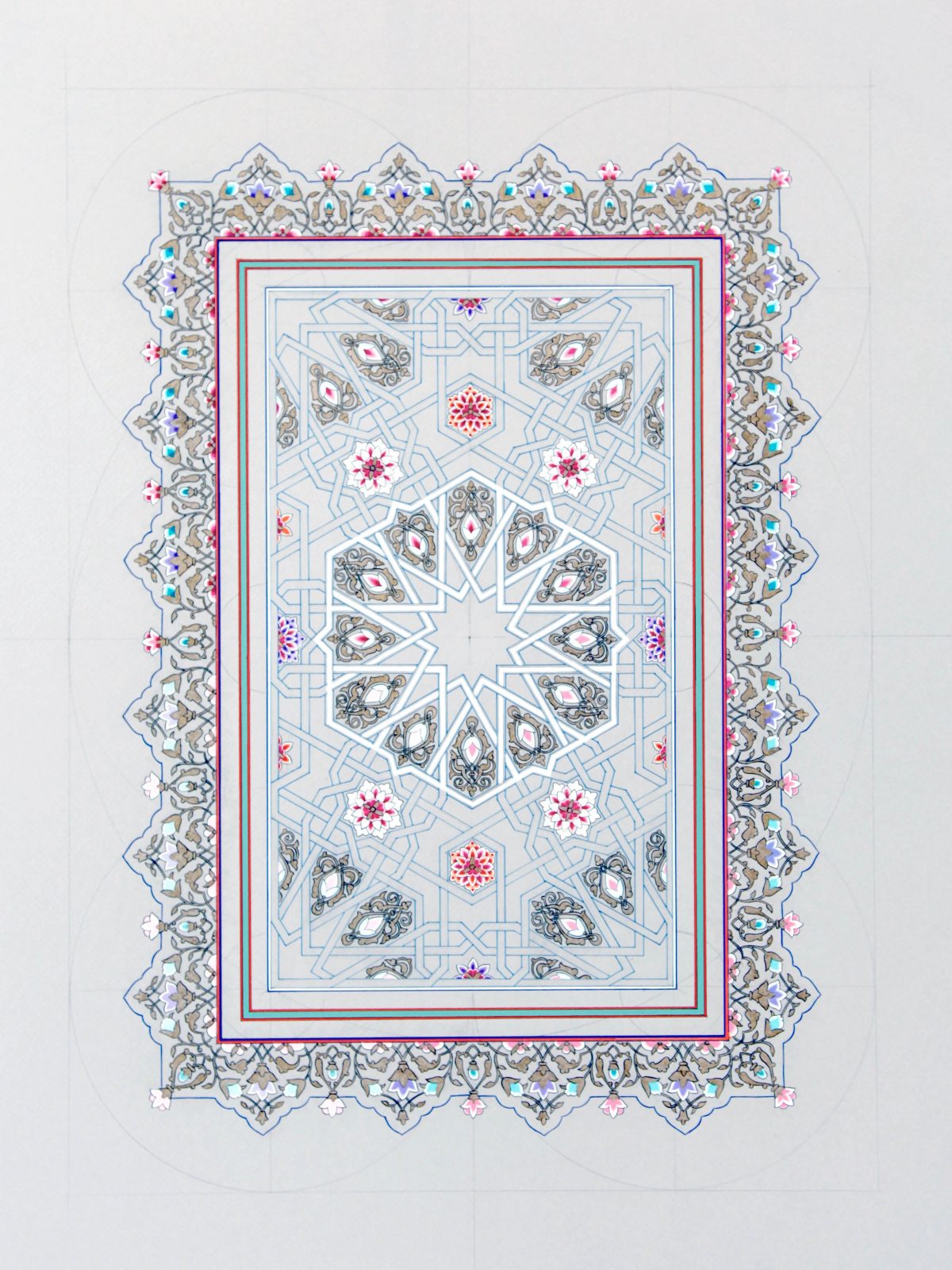

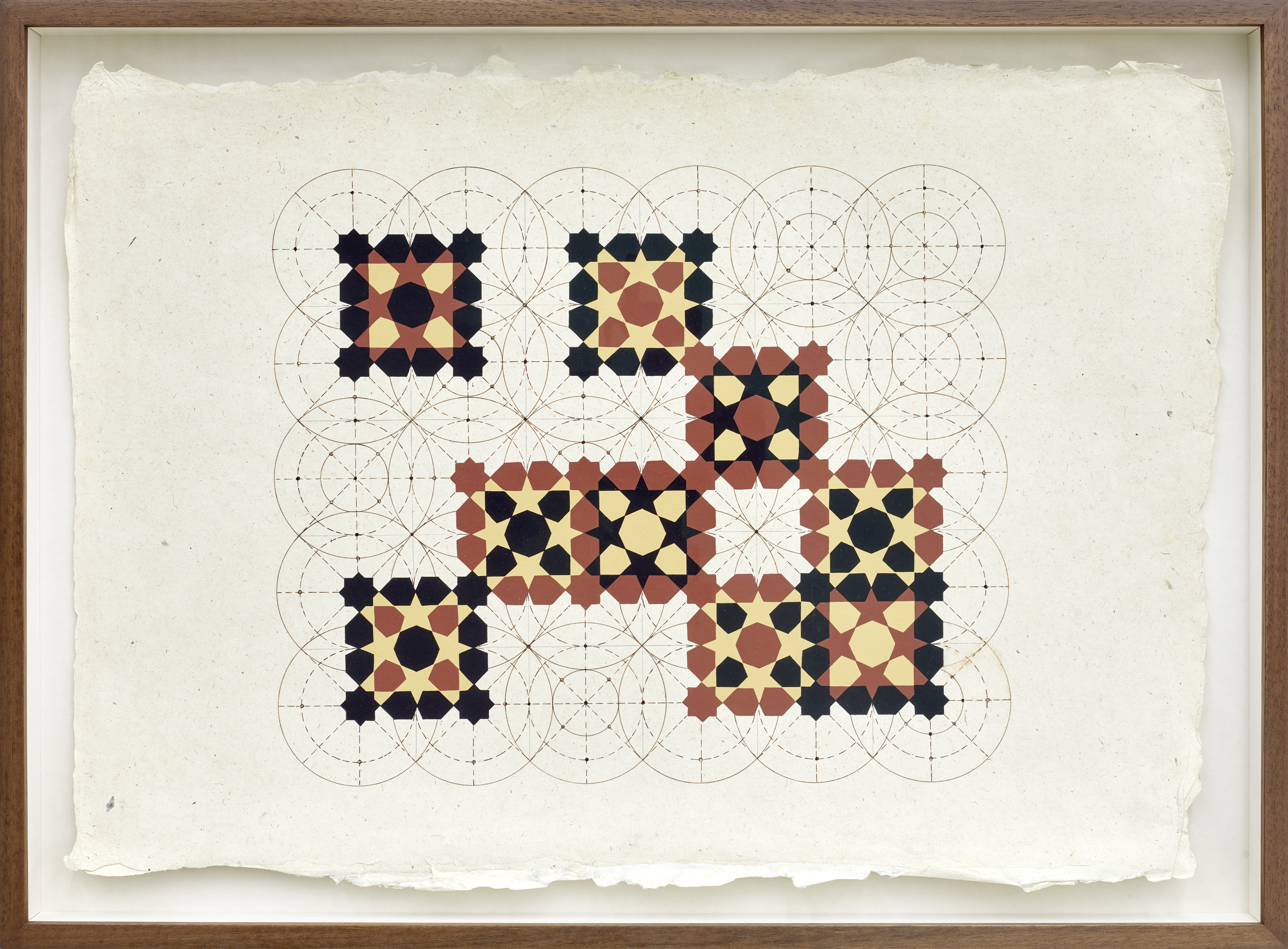

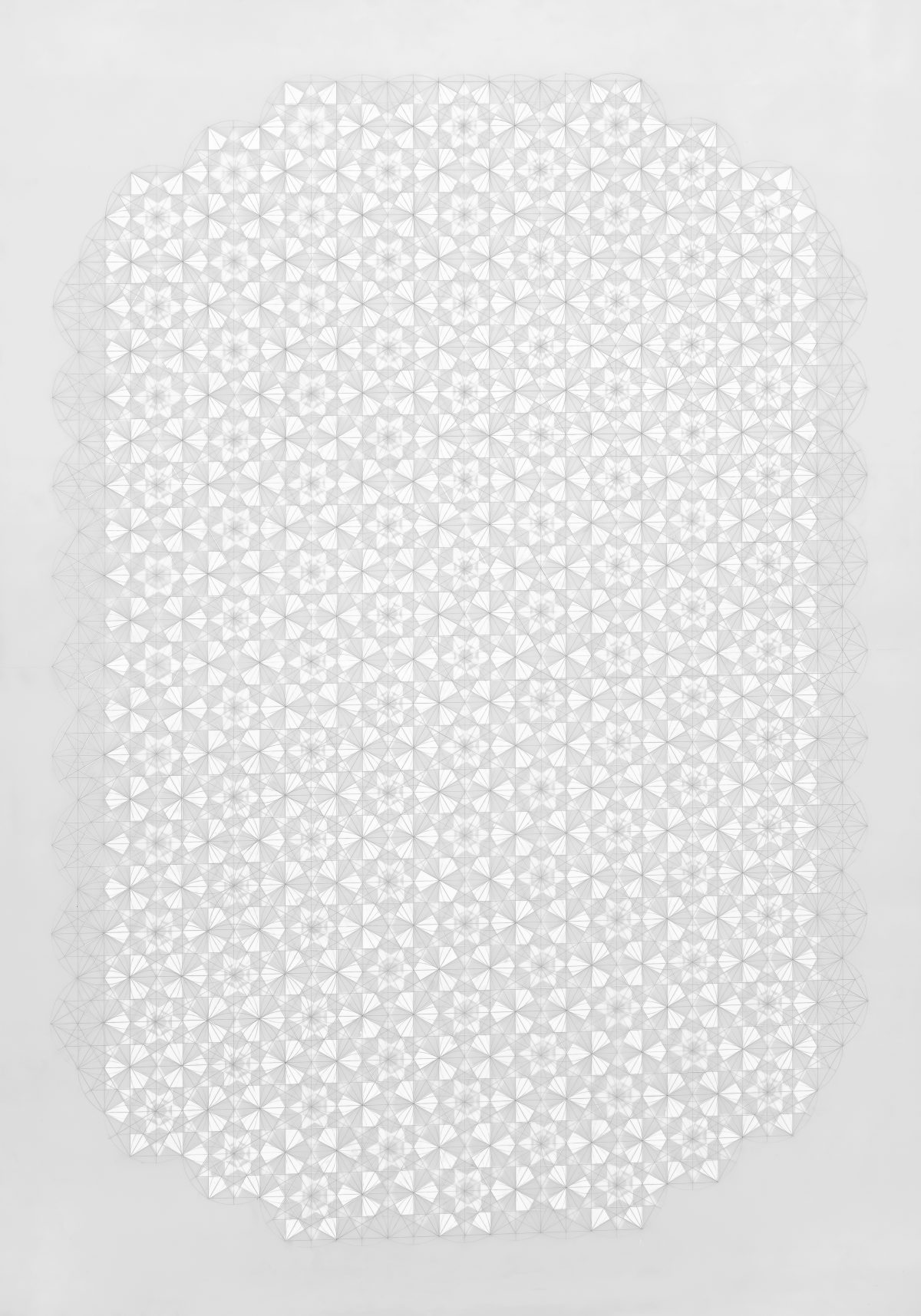

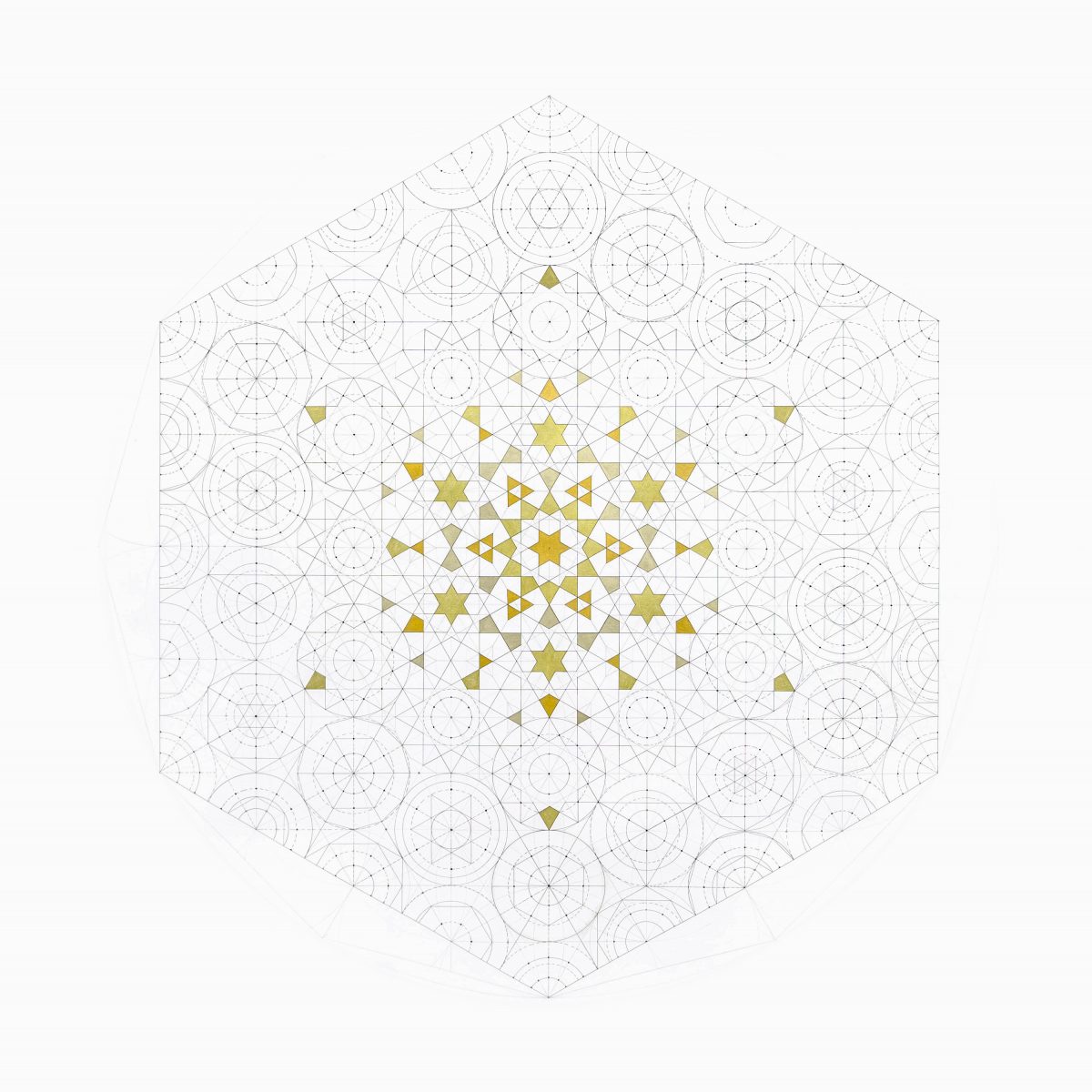

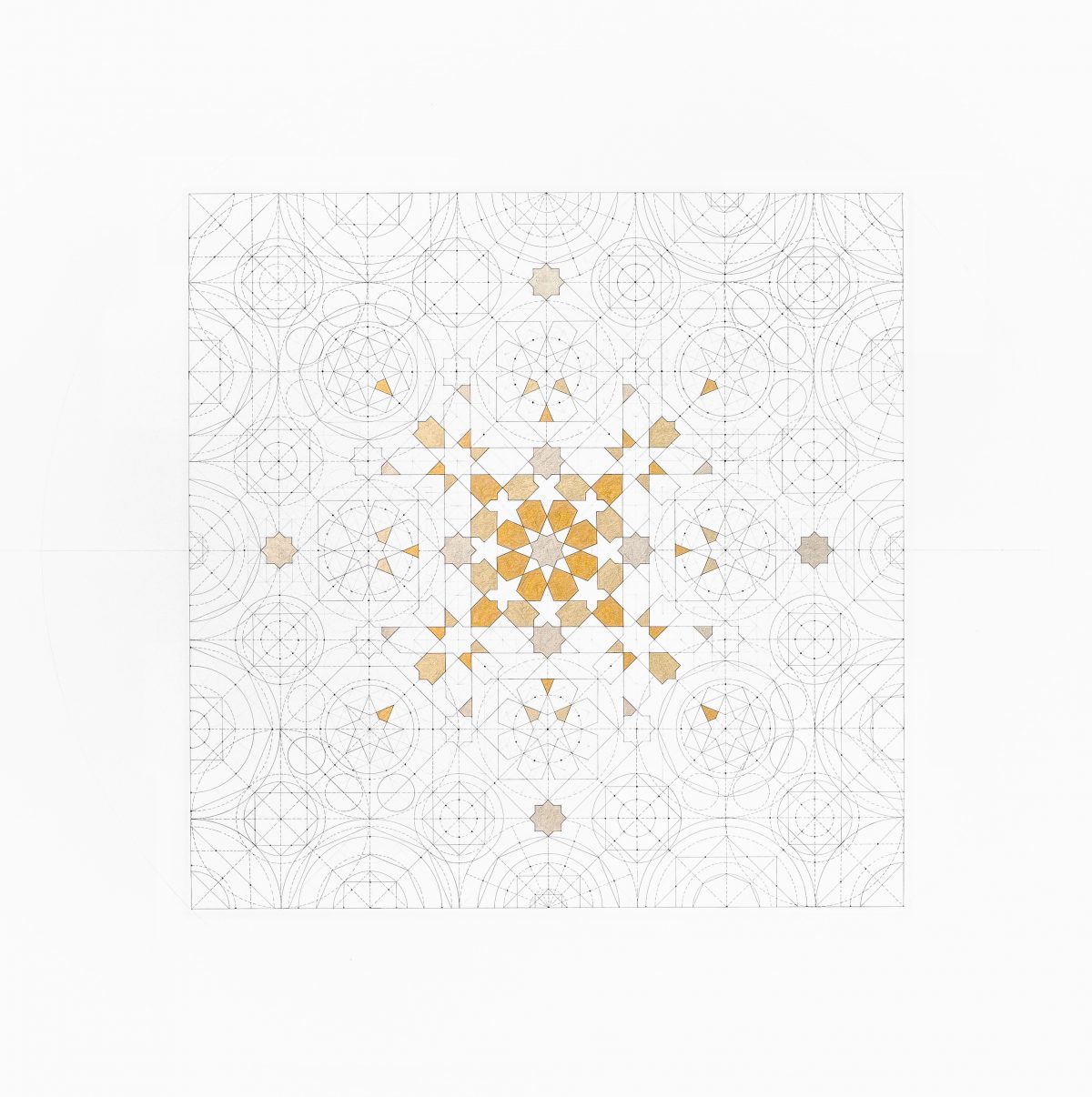

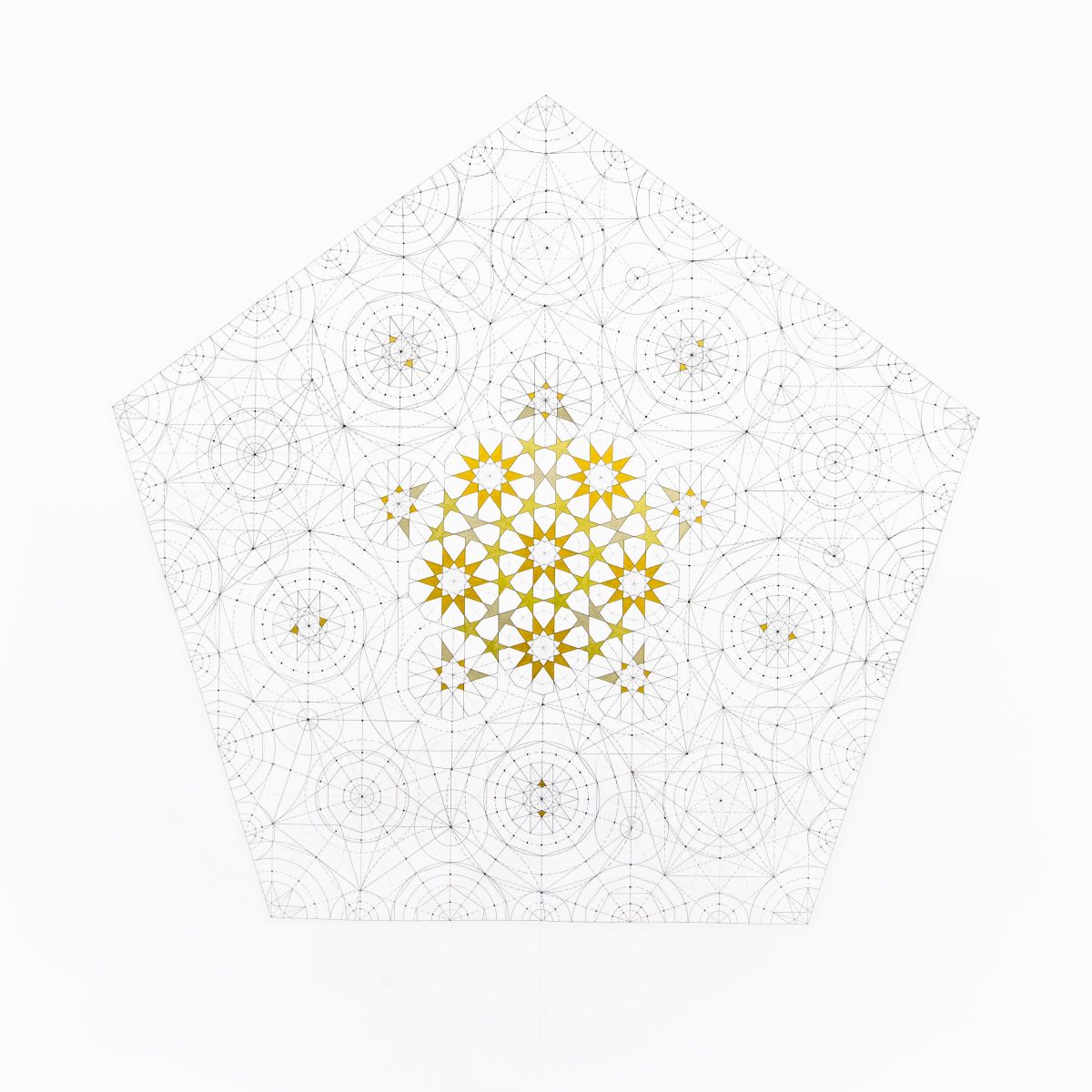

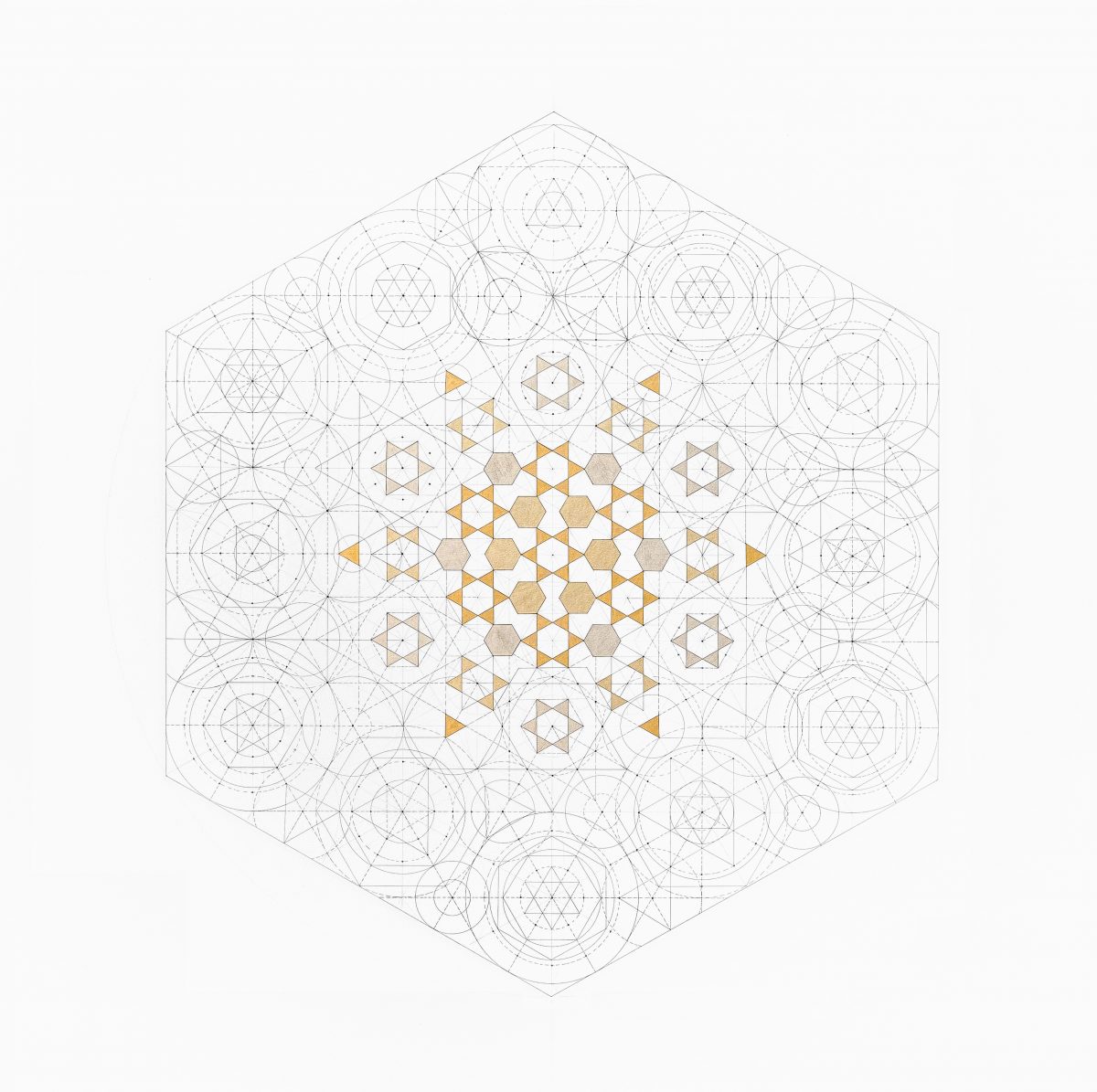

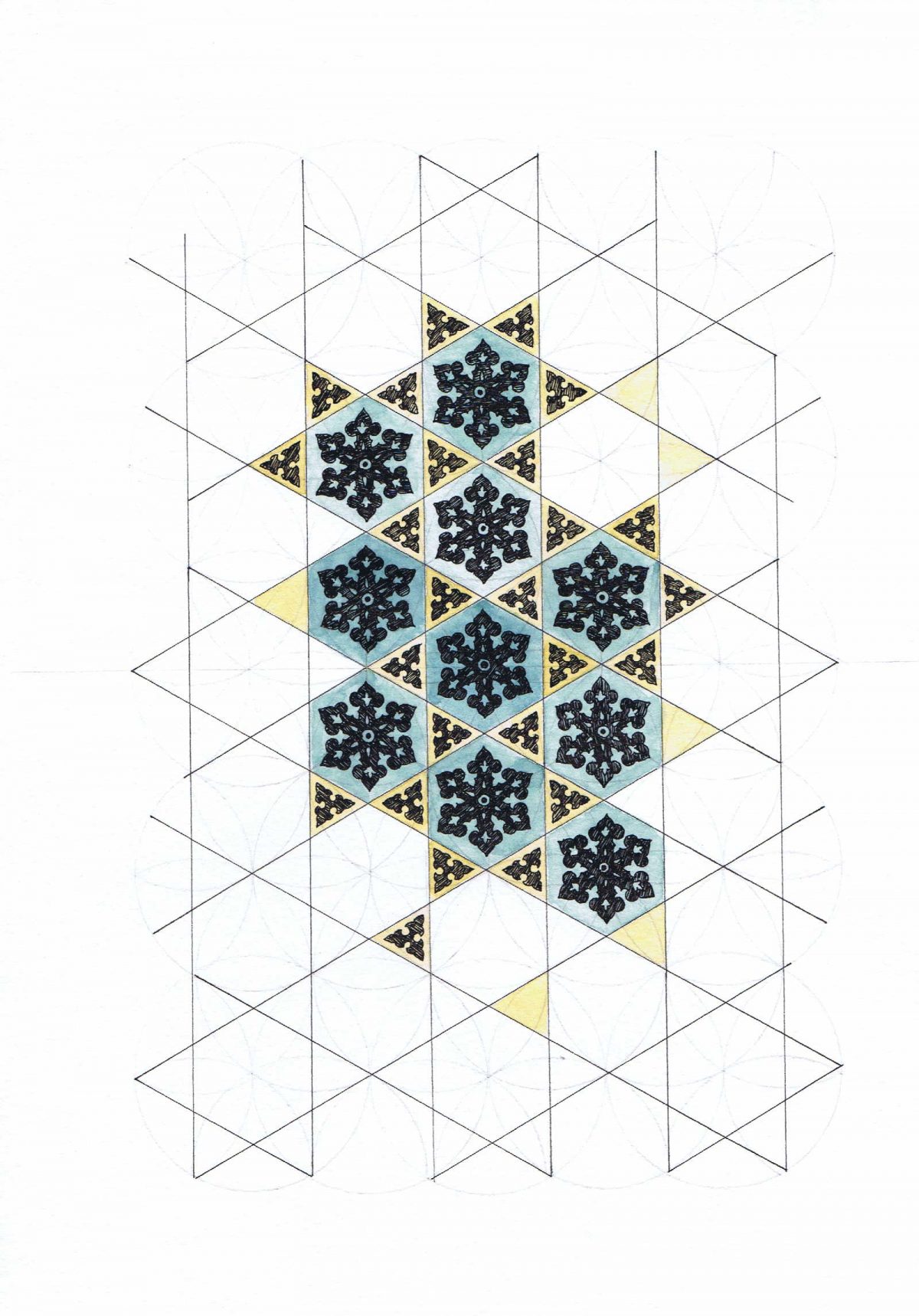

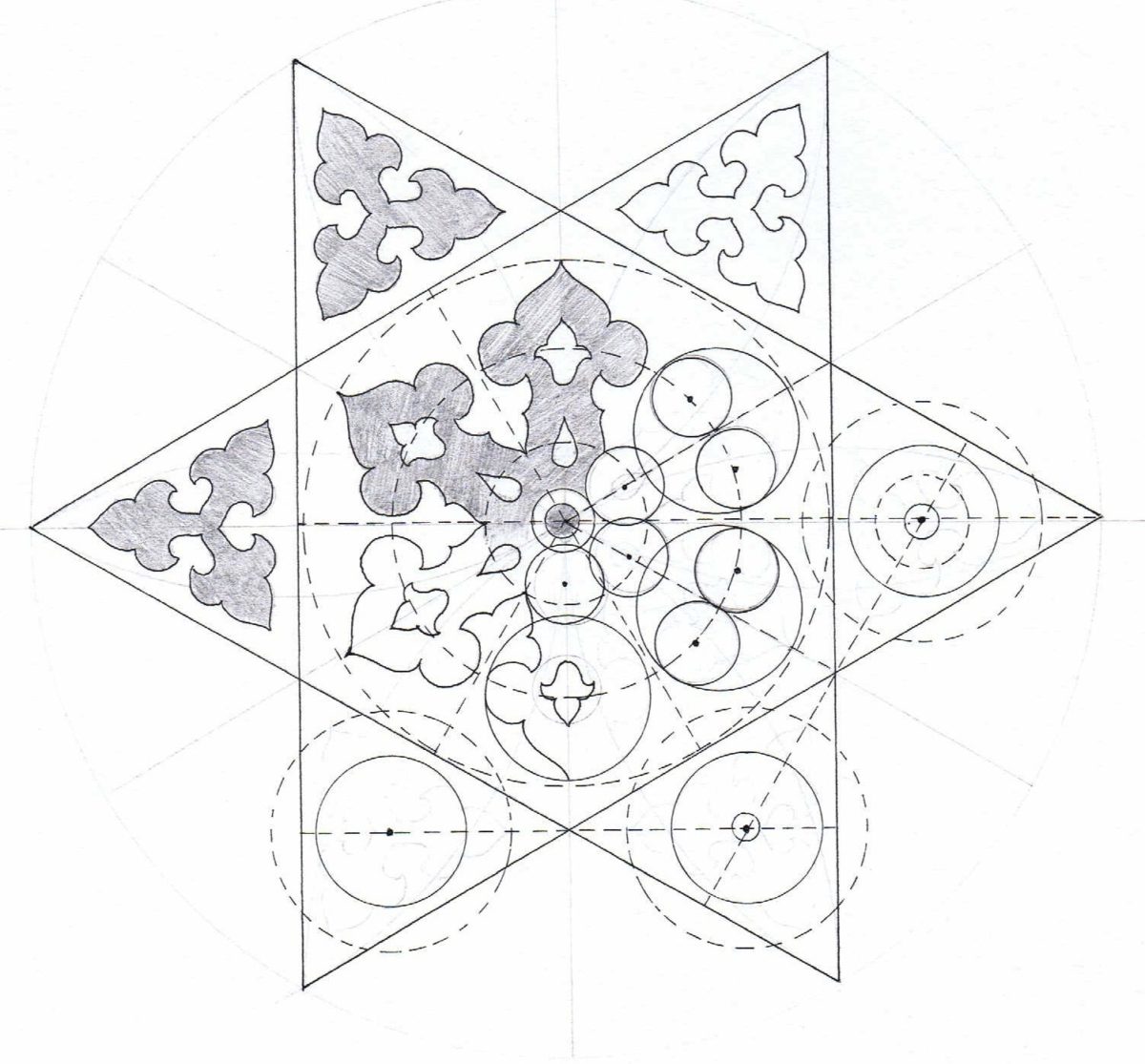

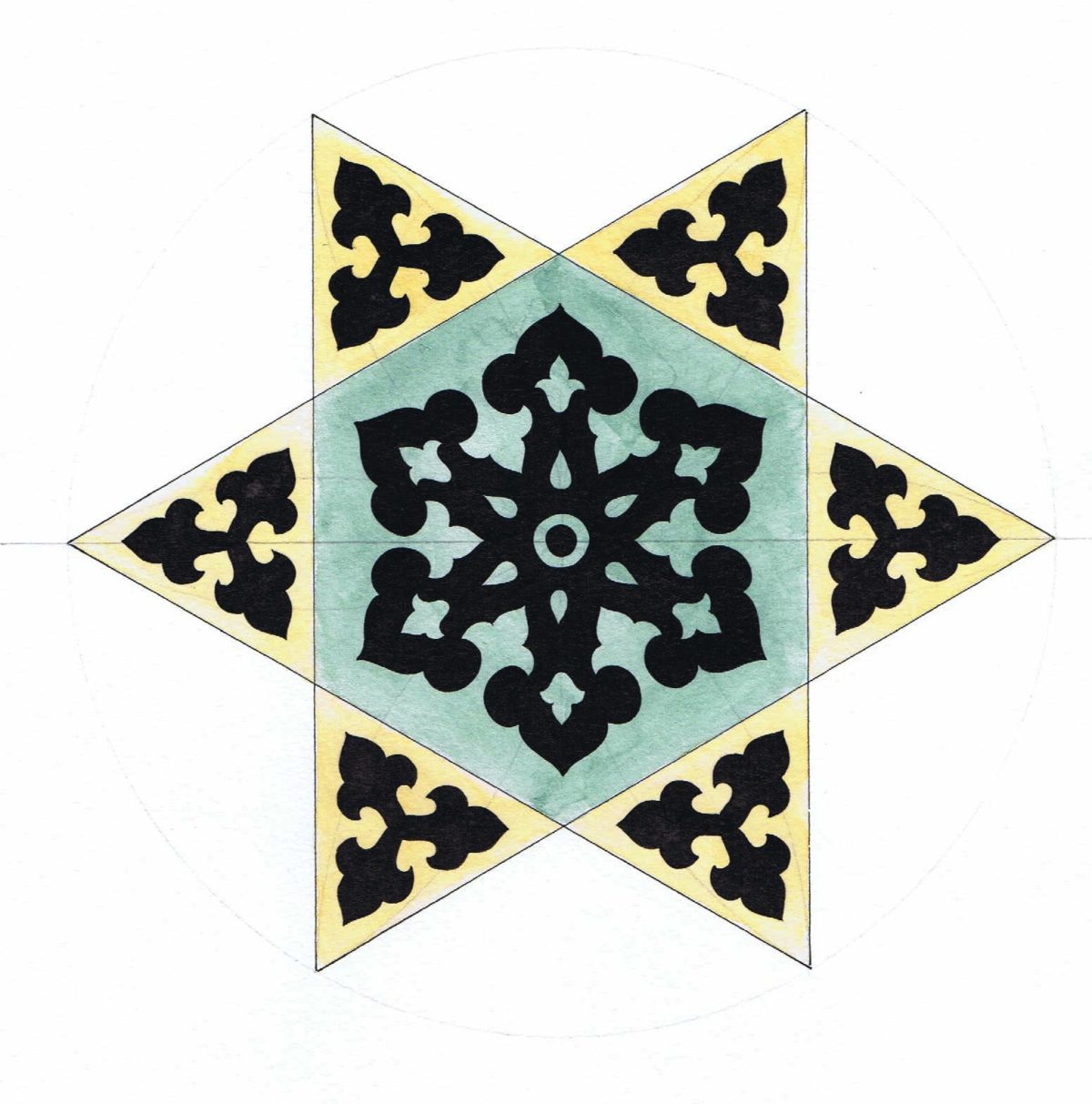

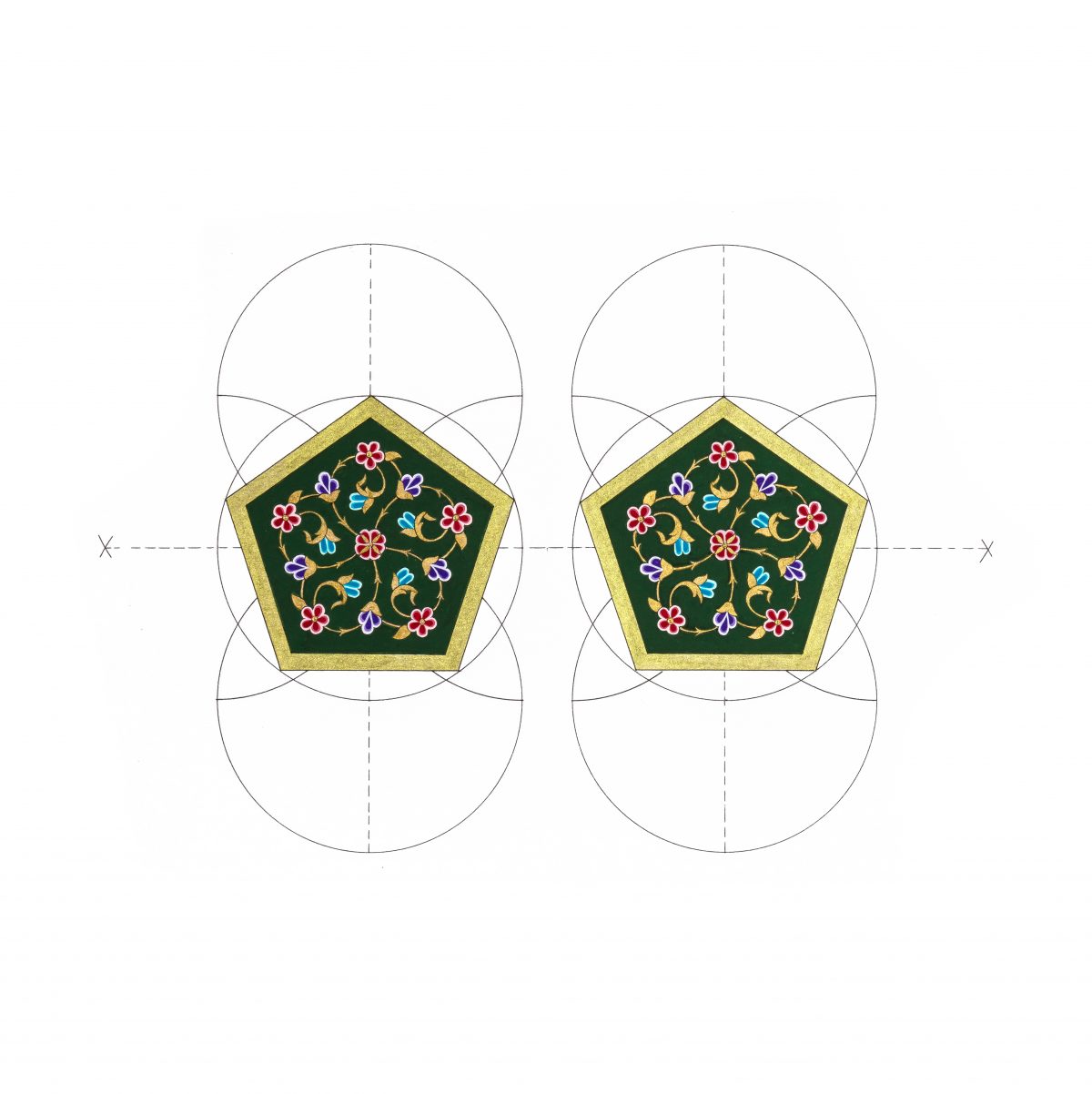

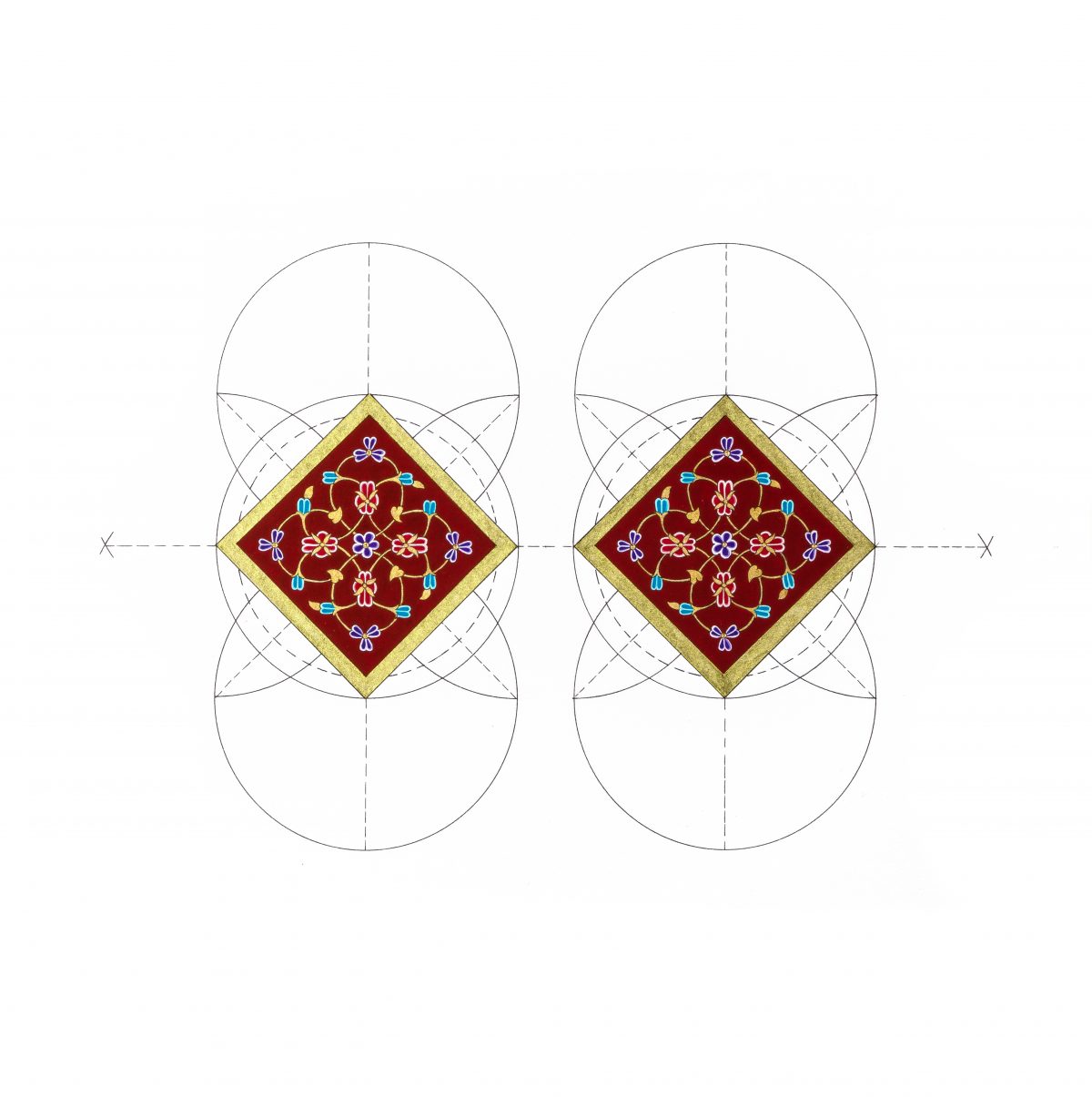

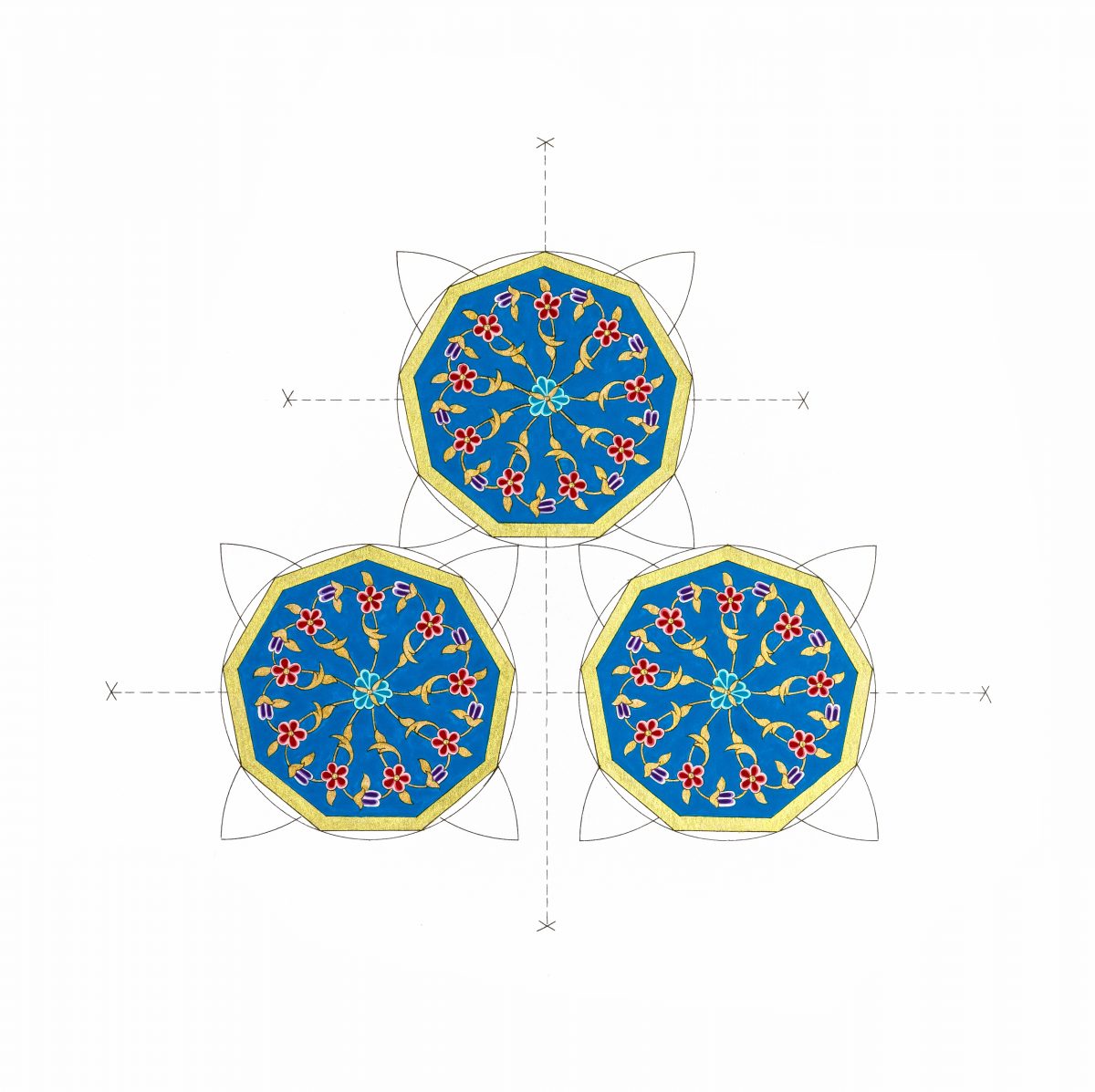

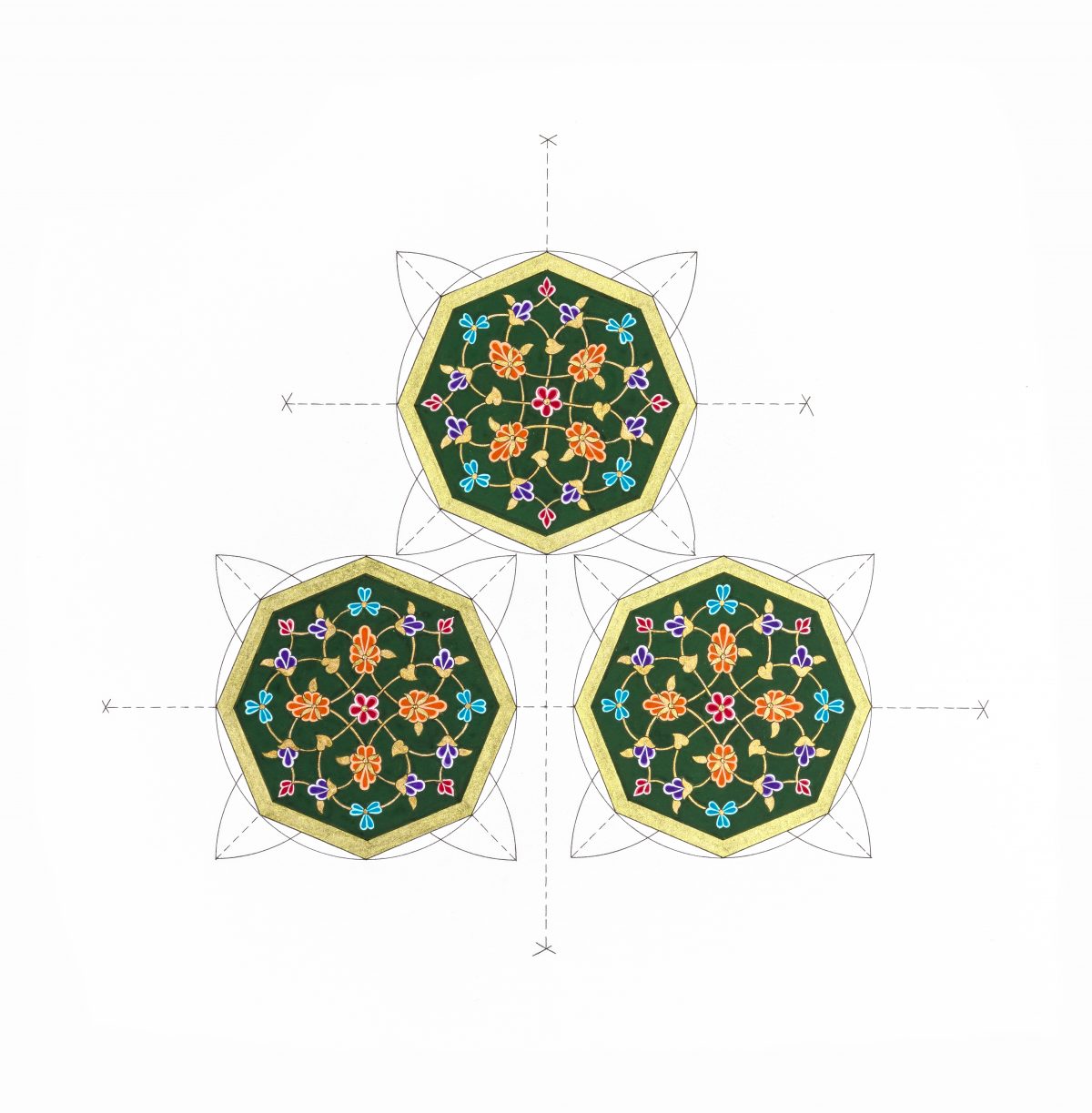

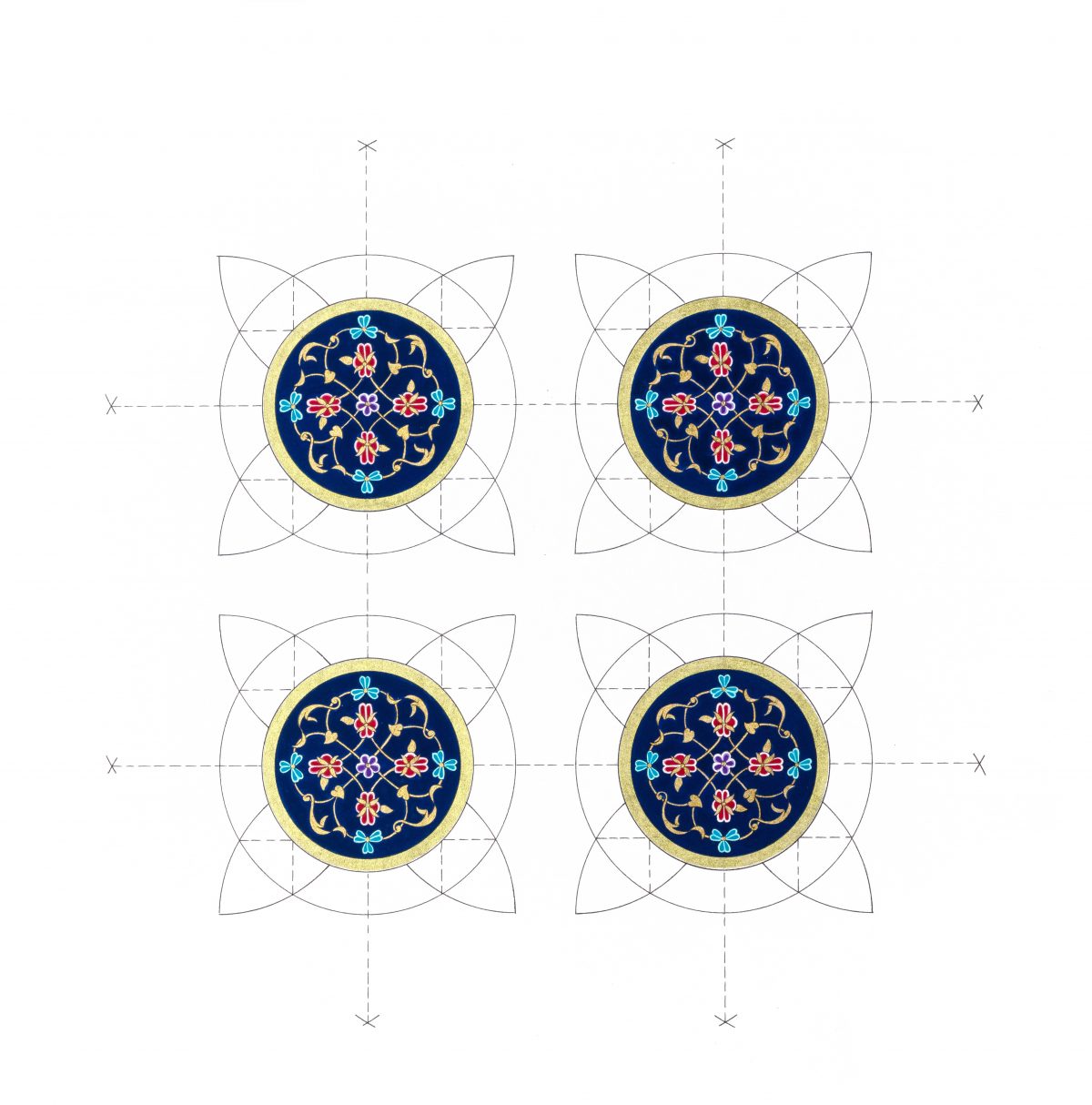

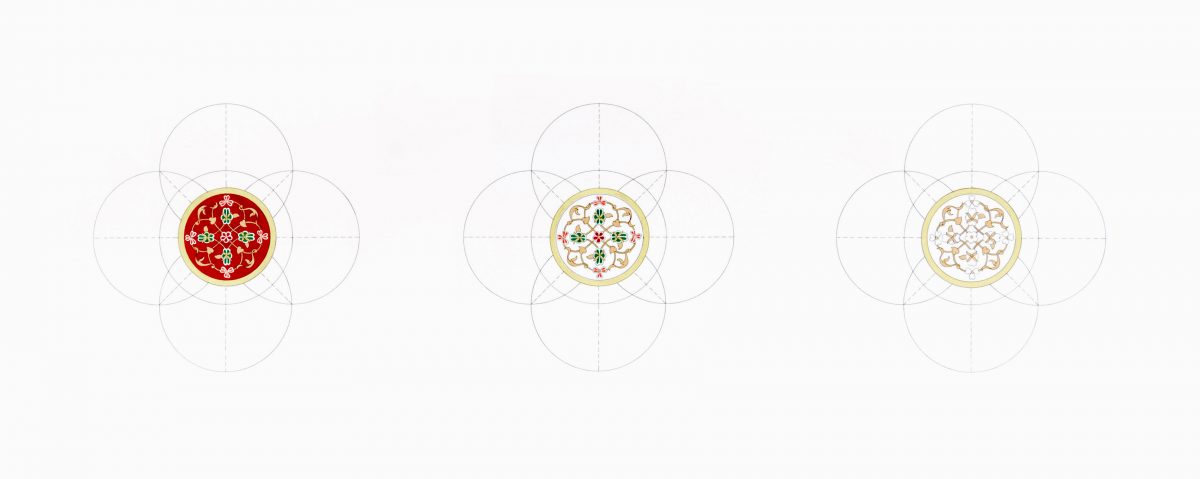

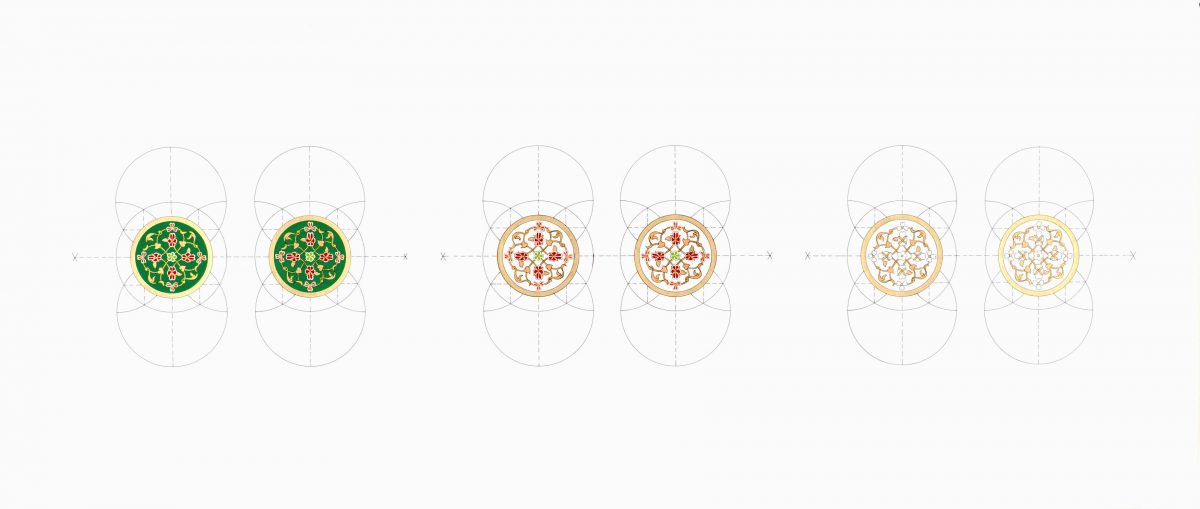

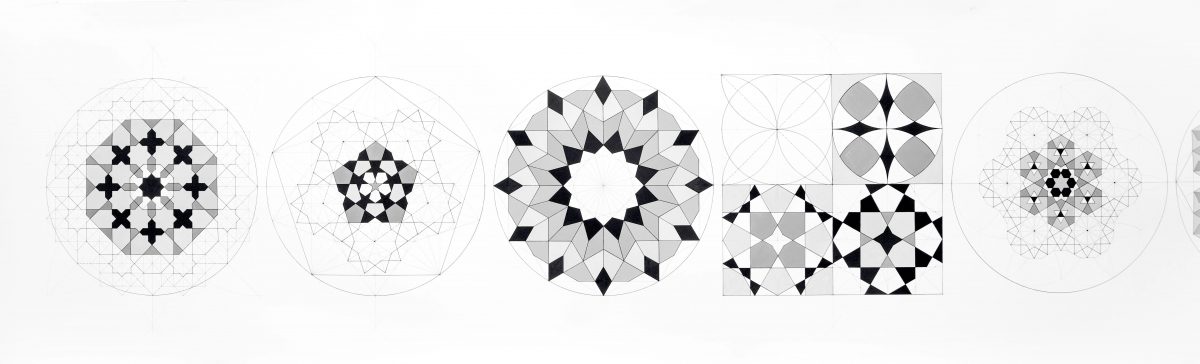

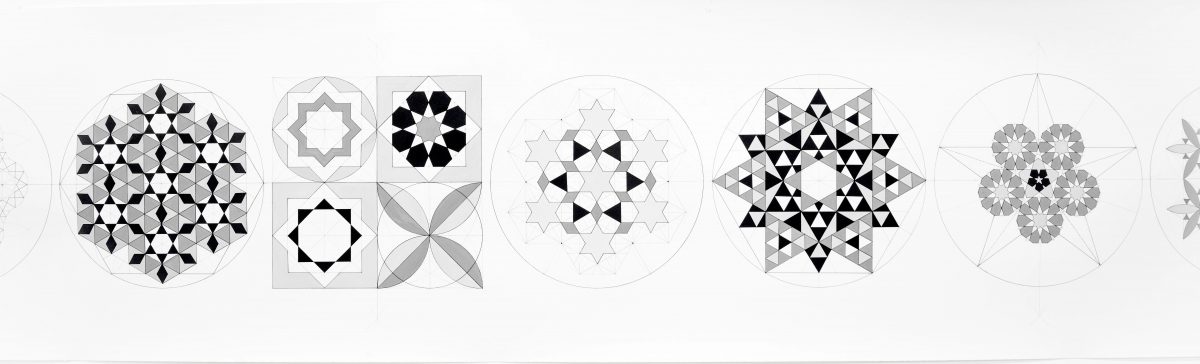

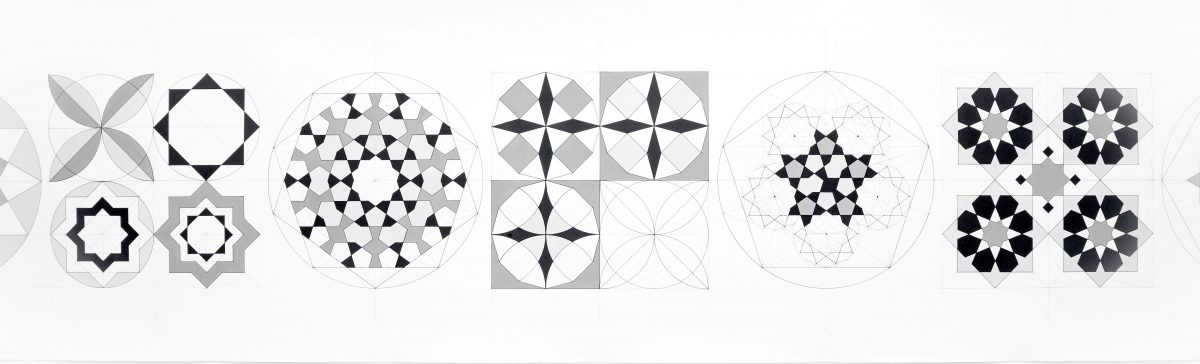

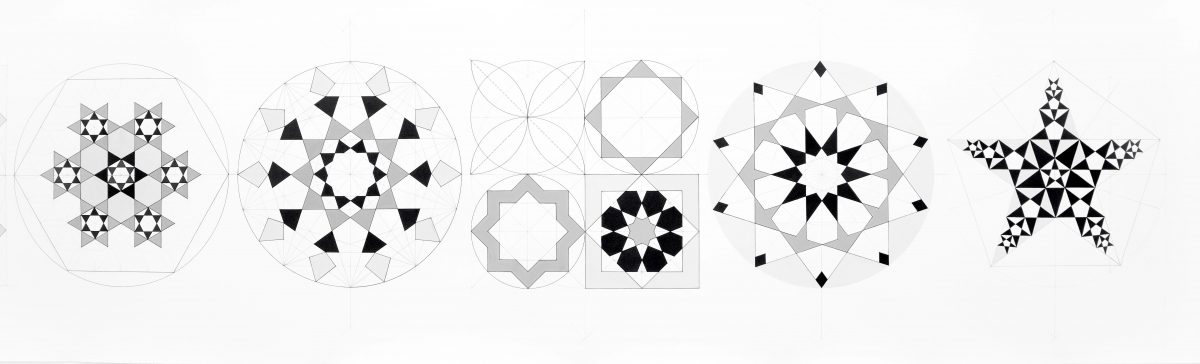

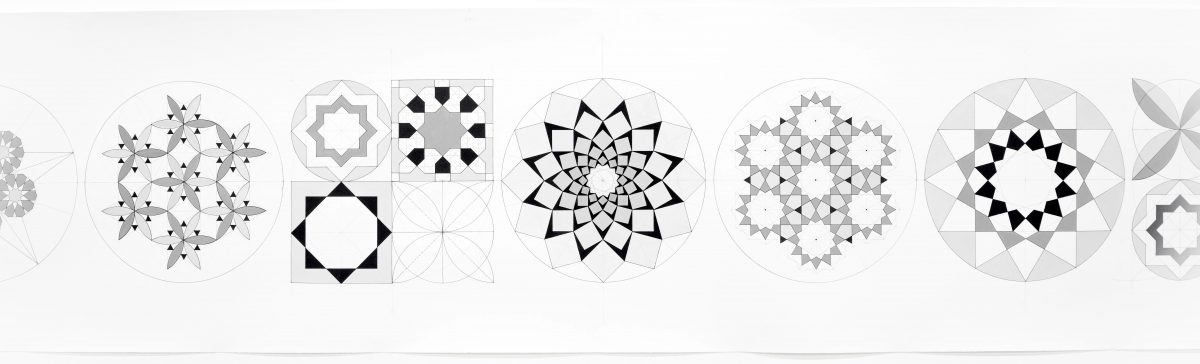

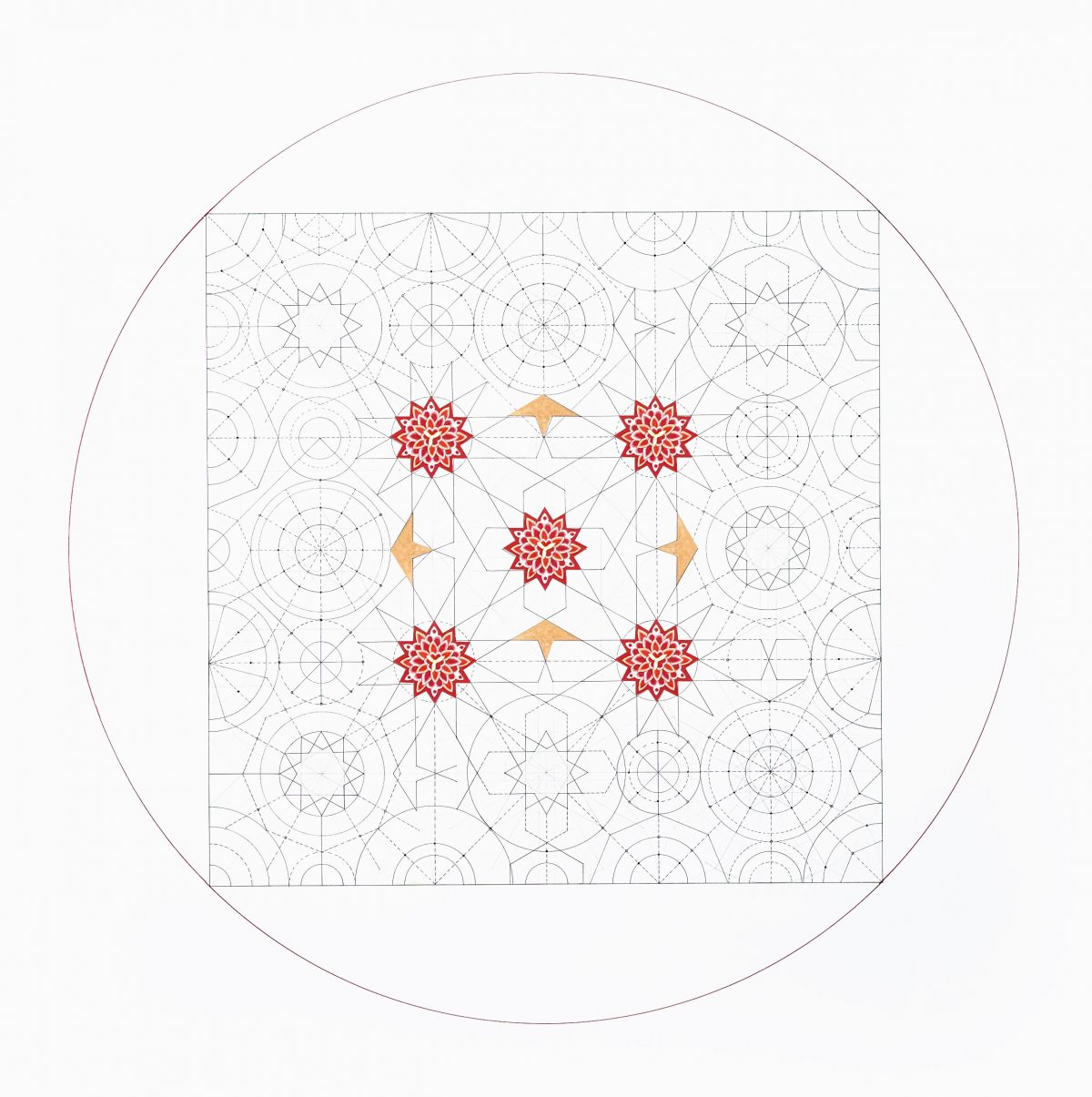

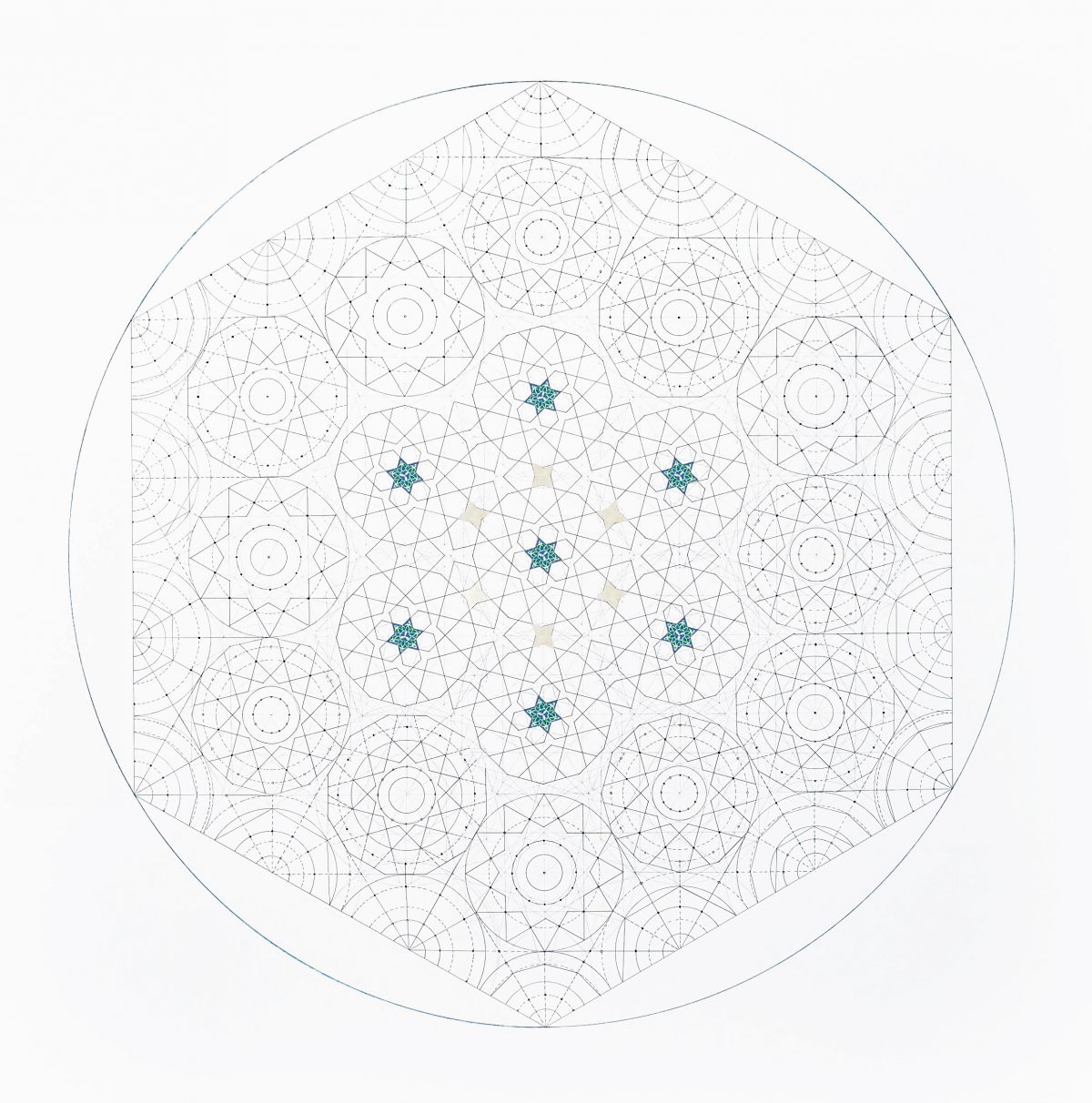

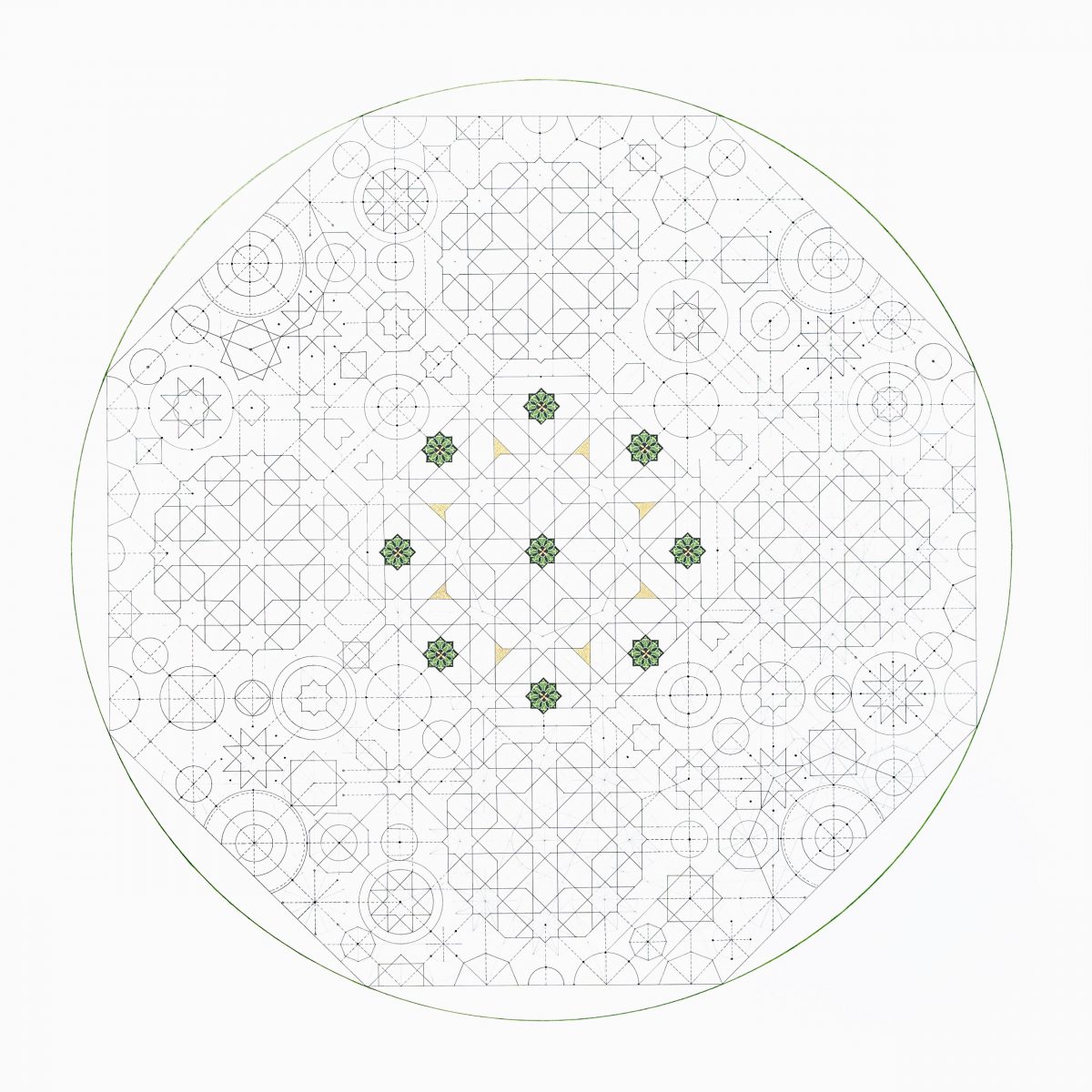

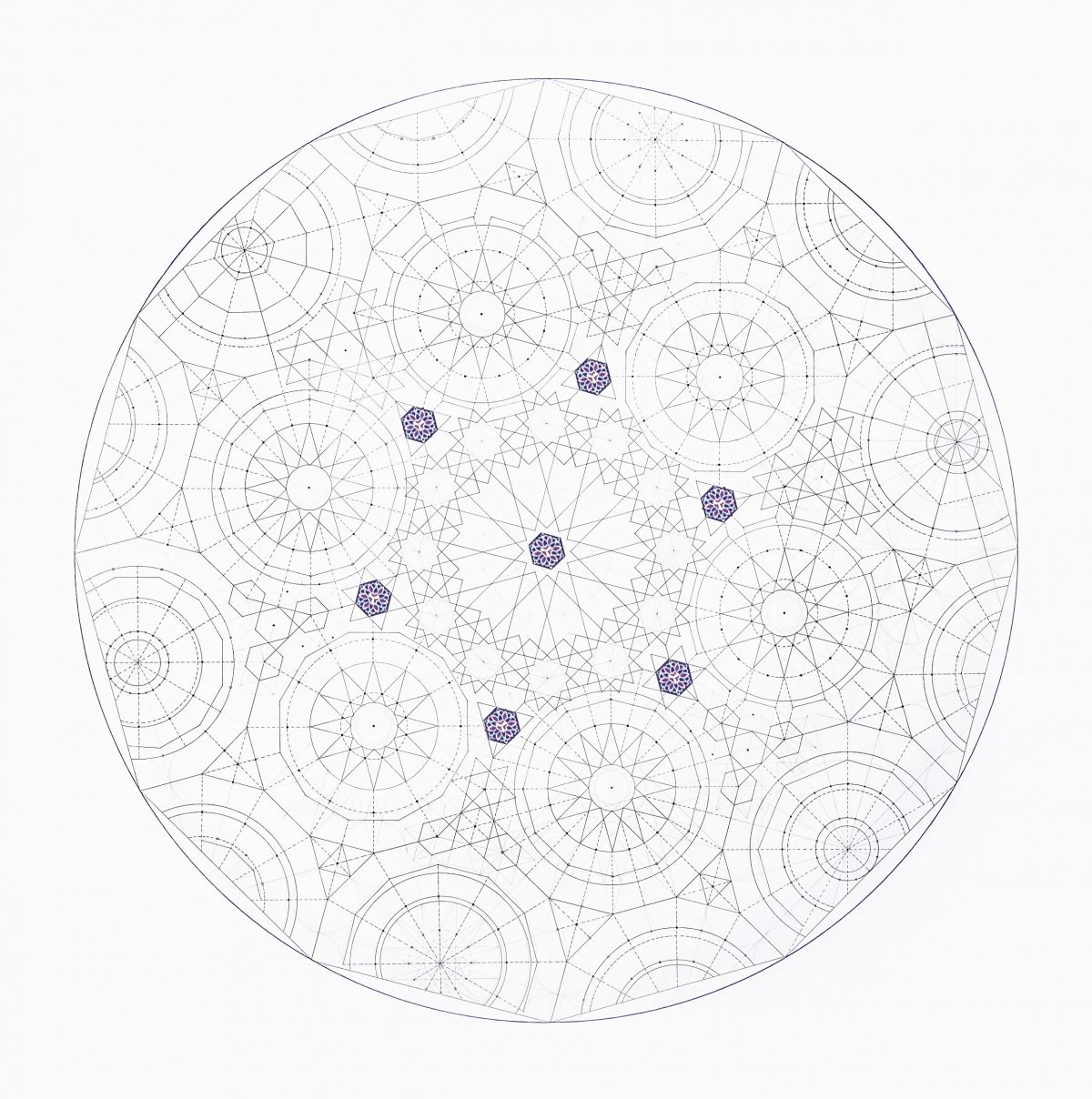

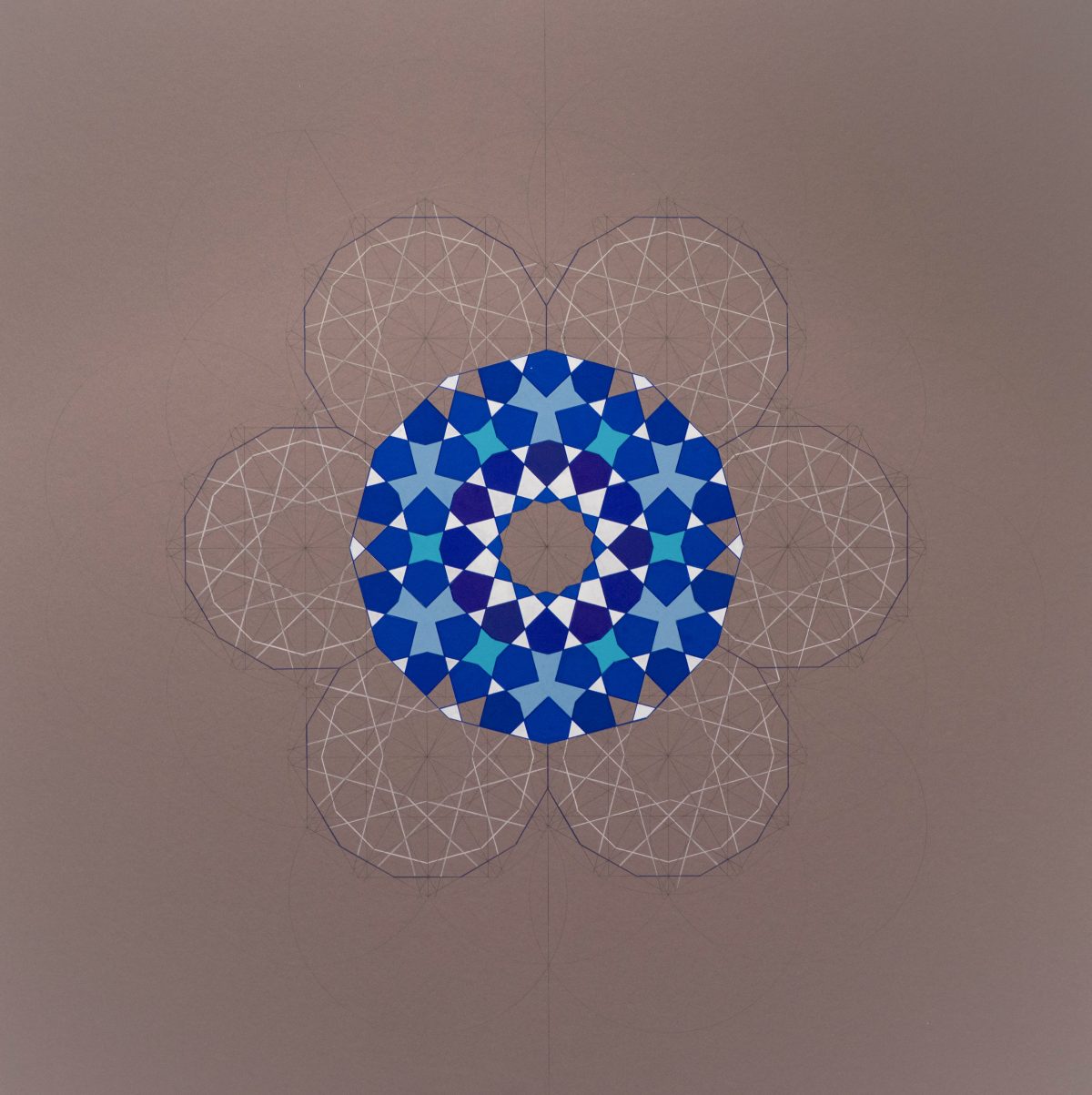

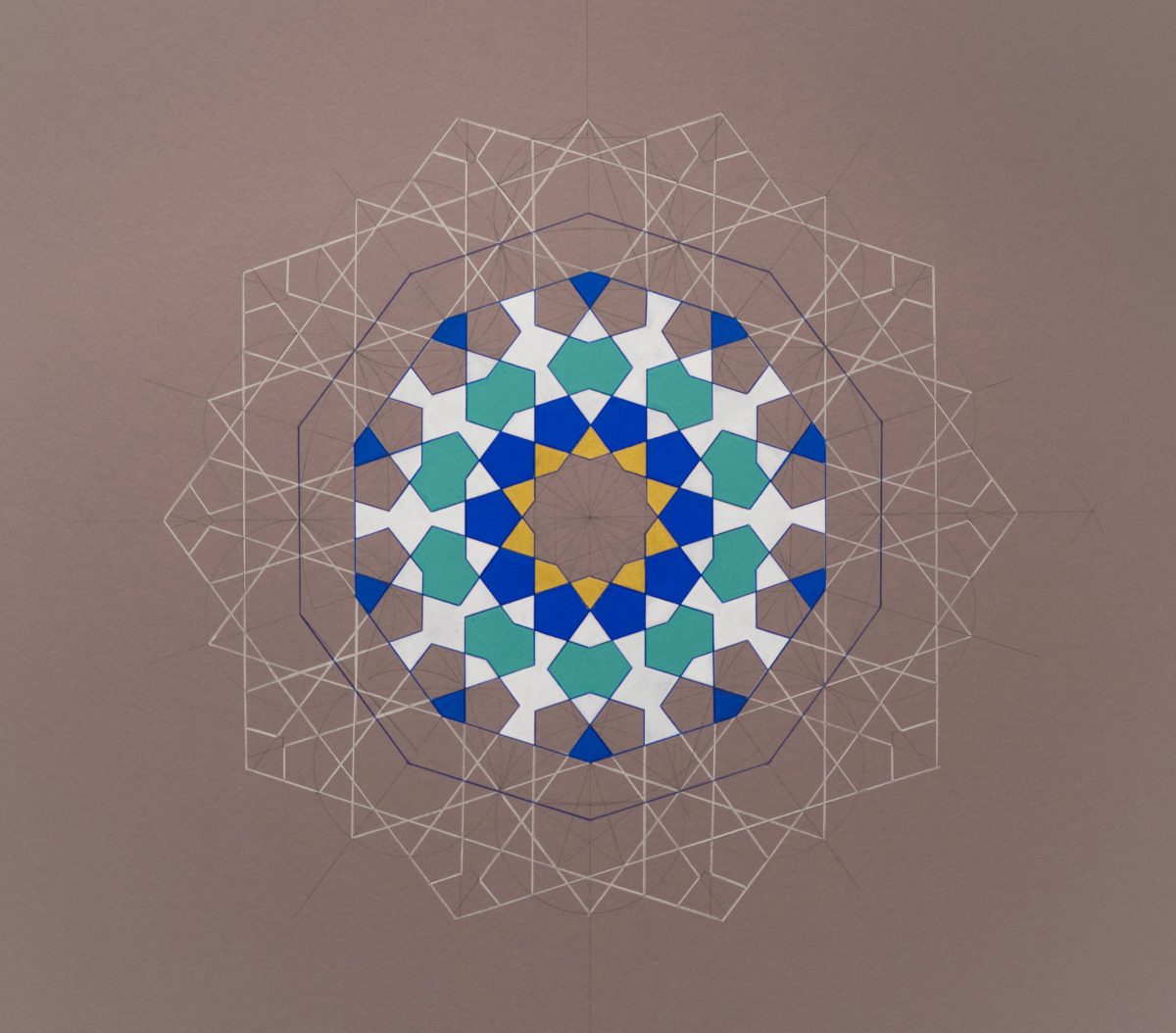

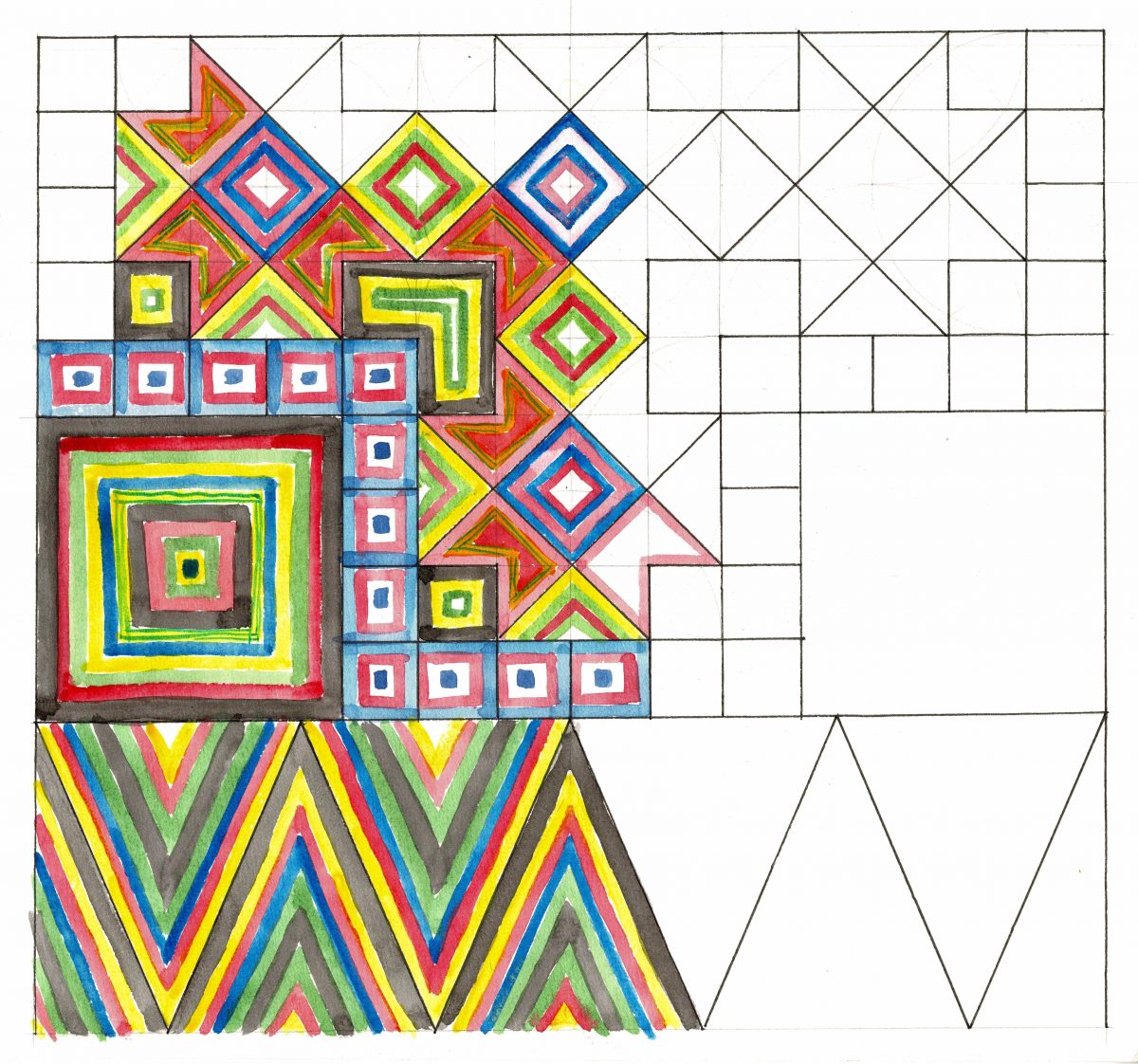

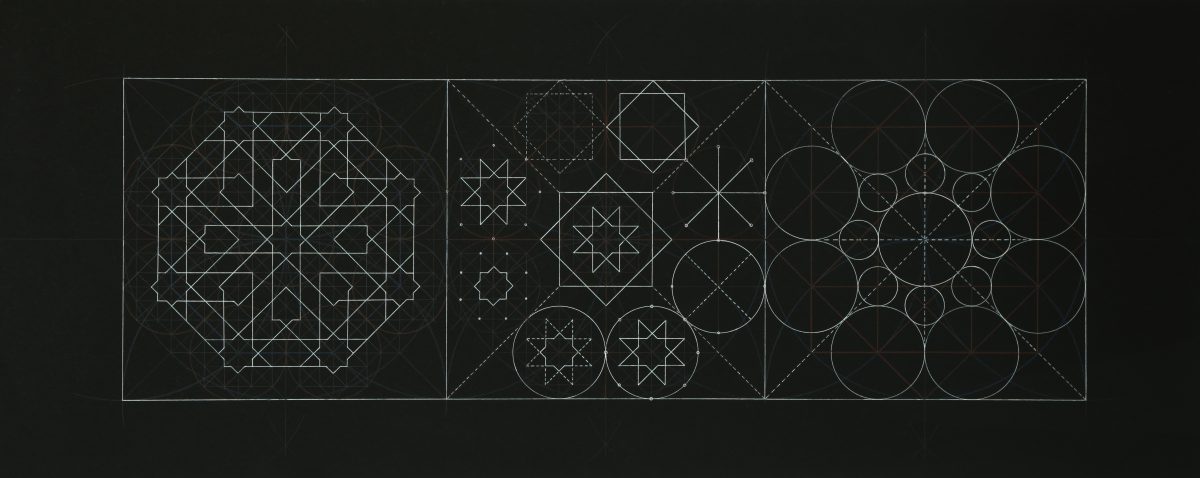

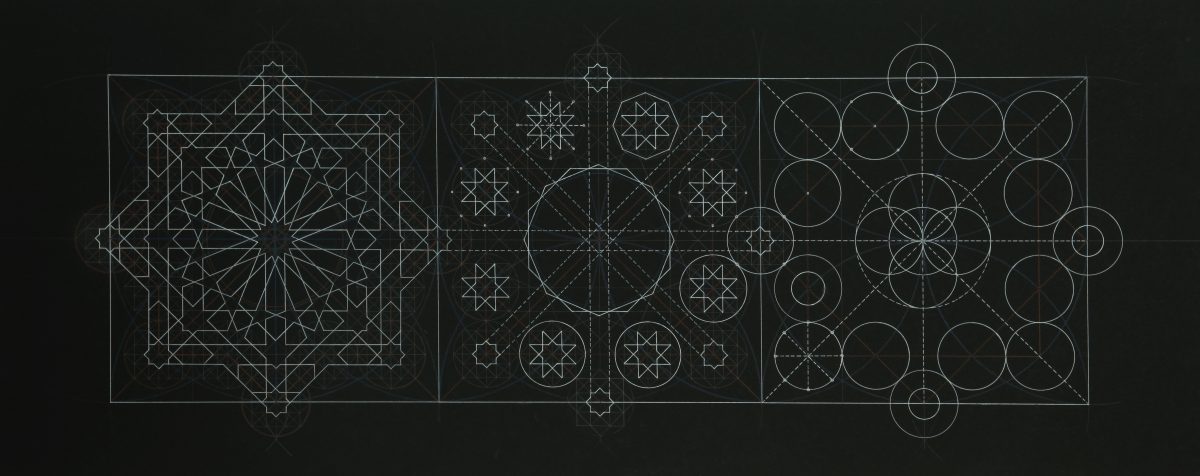

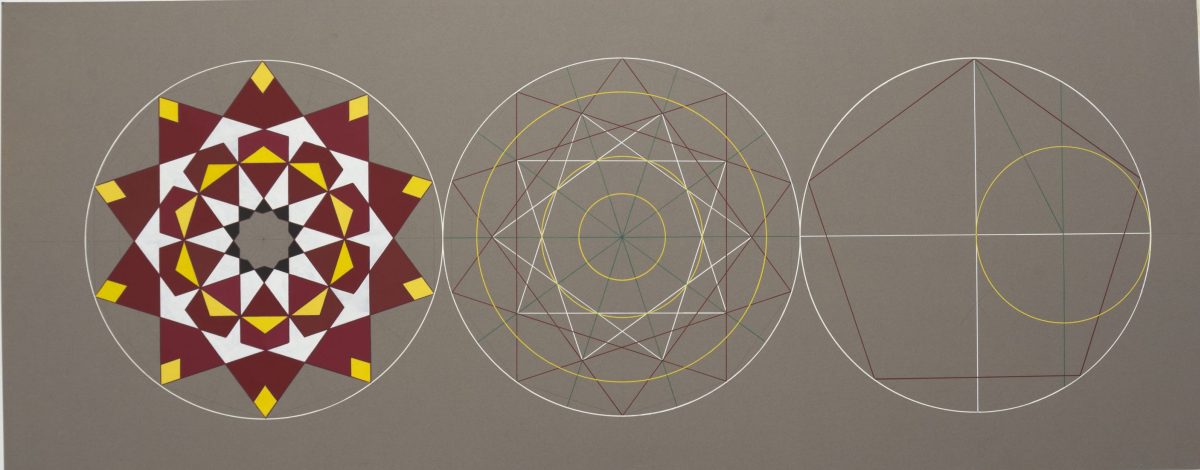

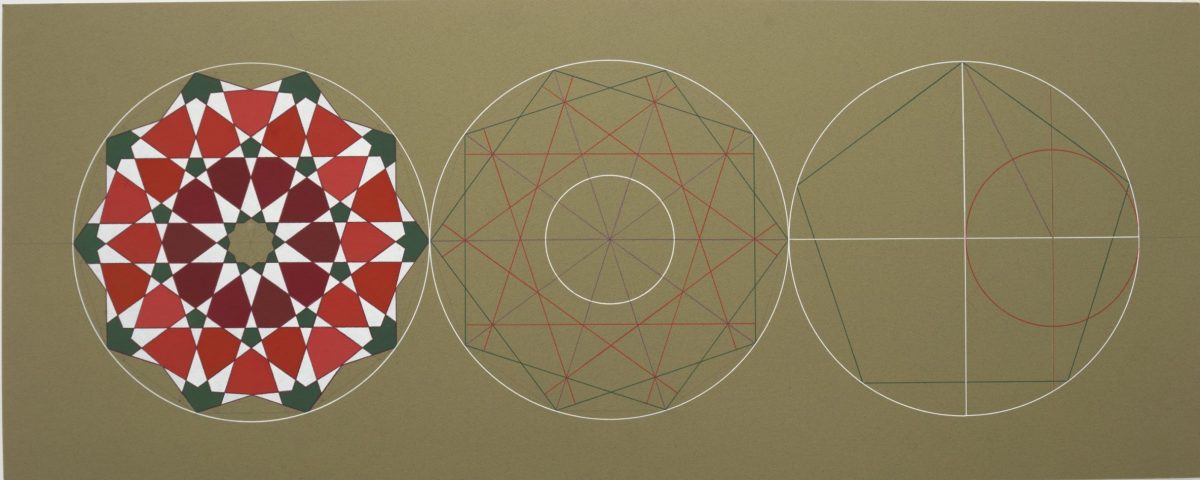

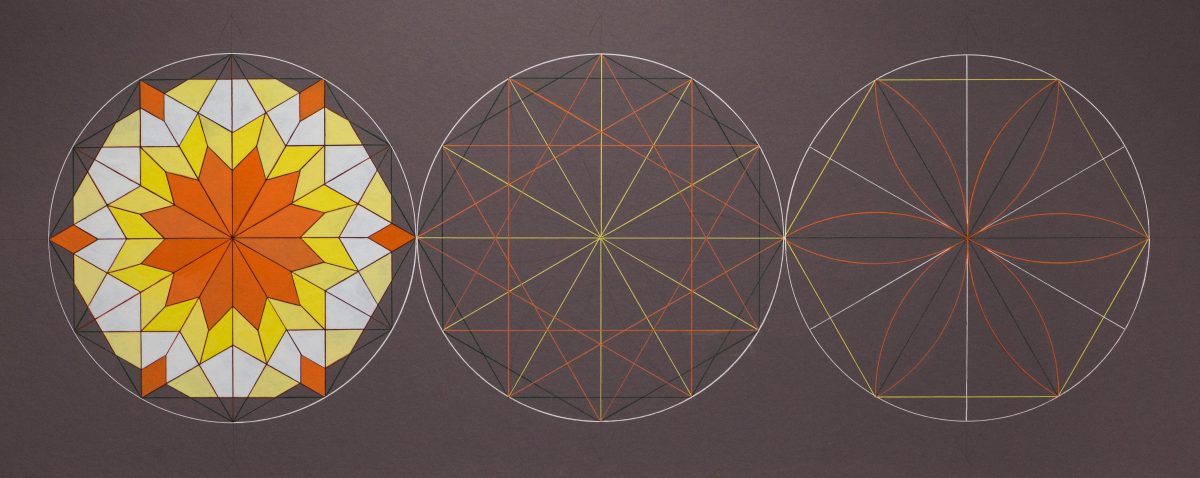

When the Dust of Conflict Settles examines the repercussions of conflict on cultural heritage, the communities that are left behind, and how we might approach the challenges of rebuilding what has been destroyed. The artwork draws inspiration specifically from the historical craft of stone masonry within the Syrian context, whereby Awartani has studied and archived the various examples of decorative stone carvings found on monuments across Syria that vary from churches, mosques, citadels, and temples, that have faced cultural destruction during the Arab spring. Relying on her training in traditional geometry, Awartani mathematically analyses the various motifs true to their original form using a compass and straight edge as a blueprint ready to be translated back into stone carvings.

For this project Awartani has collaborated with a group of Syrian apprentice stonemasons that had to leave their home cities as a result of the war and are currently residing in Mafraq, Jordan, as well a group of craftsmen from the wider Middle Eastern and South Asian diaspora who are currently living in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. The Syrian group of masons are alumni of a conservation stonemasonry training programme set up by the World Monument Fund, which aims to provide trainees that have both come from Syria and the wider local community in Jordan with stonemasonry skills that could be used to restore and repair historic monuments affected by war, as well as strive to provide the students current employment opportunities in Jordan.

The lack of skilled craftsmen remaining in Syria, as well as other worn torn areas, has severely hampered the future of conservation efforts. This depletion of professional craftspeople is a result of them being forced to flee and a lack of a network to support and train them when they leave. The transmutable skills of stonemasonry amongst other traditional crafts is not only the key to preserving and restoring historical monuments that have been destroyed, but more importantly can aid in supporting the people from these communities in the long run by equipping them with the knowledge and expertise to contribute to the restoration efforts should they choose too.

The artist intends through this artwork to bring awareness to the importance of the continuation of traditional knowledge in reconstructing the future, how craft enables the process of healing and contributes towards the efforts of rebuilding what has been erased. Awartani believes it is important to economically incentivise the preservation of traditional craft and support the livelihoods of the master craftsmen who uphold this knowledge, for us to retain a part of our collective history and have it play a crucial role in the present.

When the dust of conflict settles, 2023, hand carving on griesa, jerashi, madaba, hoota and qassimi stone, various dimensions. © Dana Awartani

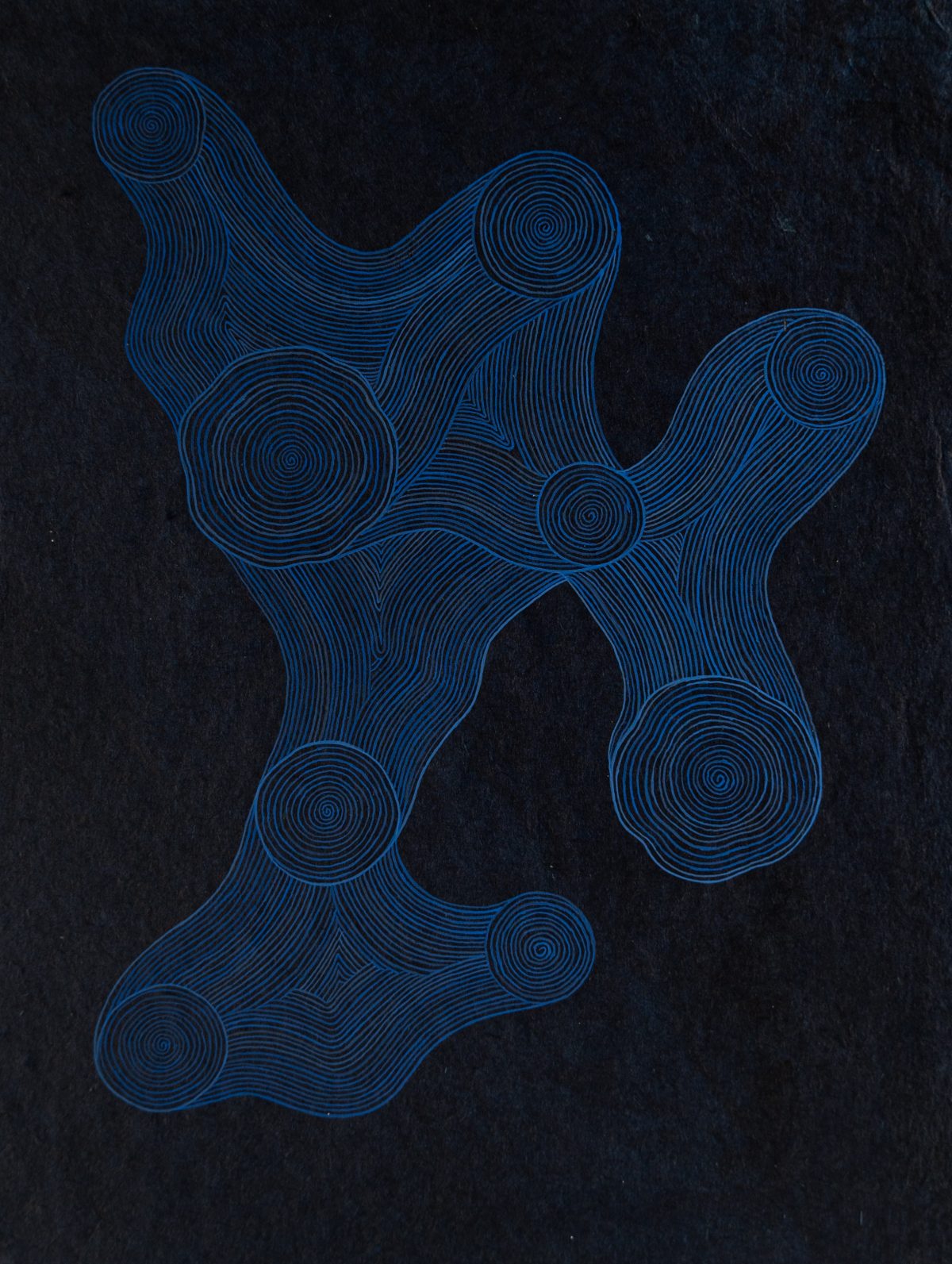

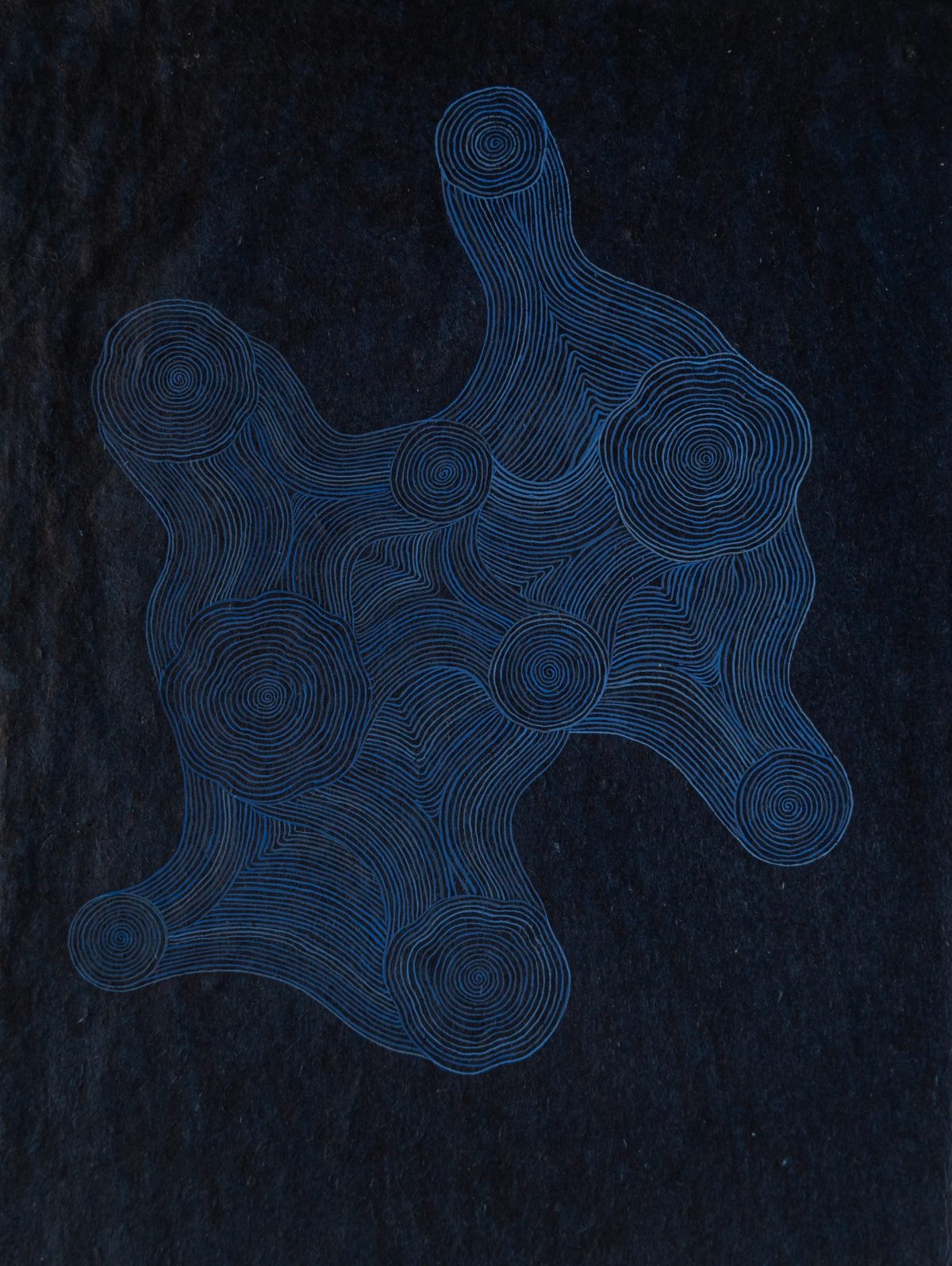

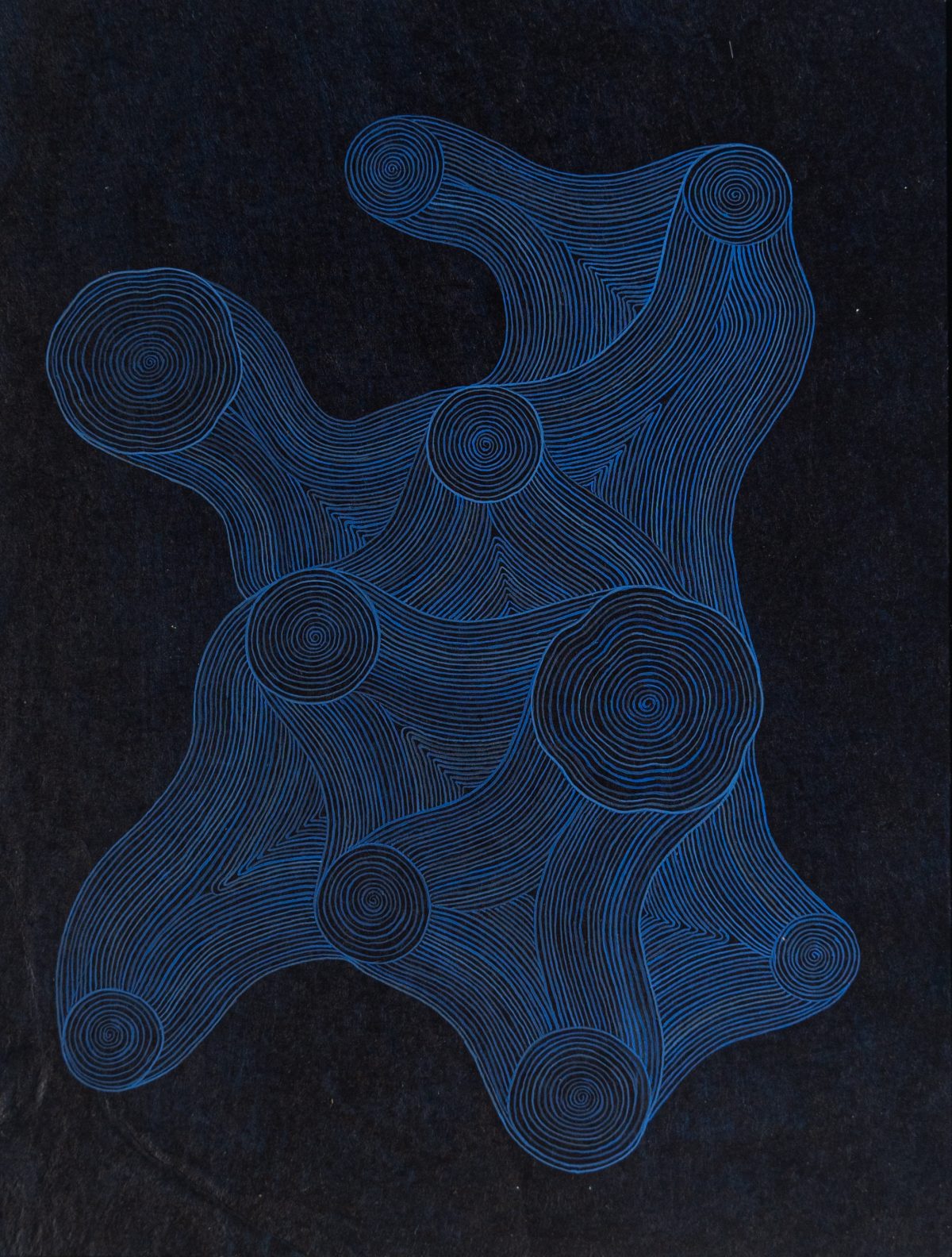

Study Drawings from When the Dust of Conflict Settles, 2023, Gouache and walnut ink on handmade paper, 35 x 48 cm each. © Dana Awartani

WHERE THE DWELLERS LAY

2022

Where the Dwellers Lay is a sculpture that draws inspiration from the vernacular architecture of AlUla. Inspired by the archaeological site of Hegra, Awartani’s artwork takes the form of a concave geometric sculpture that references the Nabataean tombs and their decorative facades. The 10-fold design of the structure is rooted in both the stairwell pattern that is commonly found carved on the exterior of the tombs, as well as in the artist’s expertise in Islamic geometry, making it an artwork that fuses the different cultural civilizations that have inhabited Saudi Arabia.

This cave-like structure, that is made out of locally sourced stone, is intended to be a space of contemplation and reflection. Placed amongst the rock formations of AlUla, the sculpture pays homage to its environment by using earth tones of the landscape allowing it to blend into its environment giving it a sense of belonging and continuity.

Where the Dwellers Lay. 2022, Sandstone and Oxidised Steel, H 315 cm x W 315 cm x D 223 cm. © Dana Awartani, Images courtesy of Lance Gerber and the Royal Commission for AlUla.

STANDING BY THE RUINS OF ALEPPO

2021

Standing by the Ruins of Aleppo engages with the theme of cultural destruction through the subject of the Grand Mosque of Aleppo. The mosque suffered serious damage during the Syrian Civil War, including the destruction of its thousand-year-old minaret during fighting in 2013. As an artist of mixed Palestinian, Saudi, Jordanian, and Syrian descent, Awartani pays homage to her Syrian matrilineal heritage in particular, focusing on an aspect of family history often overlooked within Arab societies. The artist built a large-scale replica of the mosque’s courtyard, more than twenty meters long and ten meters wide. She made adobe bricks with clay earth sourced from different parts of Saudi Arabia, deliberately eschewing the standard binding agent of hay, such that the structure will crack over time. The tiled floor is surrounded by an observation platform, a structure that echoes the mosque’s enclosed architecture while allowing visitors to view the work as a whole.

Standing by the Ruins of Aleppo takes its name from the Arabic trope of “ruin poetry,” known as wuquf ‘ala al-atlal, or “standing by the ruins.” Founded in pre-Islamic times, it has found new life in the work of a generation of artists reacting to the losses of war and state violence across the Middle East.

The work makes a lost piece of cultural heritage accessible again and implicitly draws parallels between Aleppo’s Ancient City and Diriyah, both UNESCO World Heritage sites shaped by histories of war and violence. Meanwhile, Awartani’s use of adobe, a low-cost material suffused with meaning and collective memory through its role in vernacular architecture, suggests a note of hope and communal resilience.

Standing by the Ruins of Aleppo, 2021, Clay Earth, 2277 cm x 1300 cm. © Dana Awartani, Images courtesy of the Dariyah Biennale Foundation and Canvas.

LISTEN TO MY WORDS

2020

In the empty expanse of the screen, a delicate pattern of straight lines and curved shapes is slowly traced by an invisible hand. In Islamic visual culture, where figurative representation is notoriously forbidden, abstract geometric compositions chart spiritual journeys and convey ideals of cosmic interconnectedness. The pattern created by Dana Awartani for Listen to my words is inspired by the ornamental motifs of jali and mashrabiya, latticed screens used in traditional Islamic architecture to regulate light, airflow, and heat in the arid climate of many Middle Eastern countries. Besides this climatic function, jali also play a socially and visually divisive role, marking the confinement of women within the domestic sphere and the impossibility of seeing them clearly.

The entrancing emergence of the geometric design becomes progressively tangled with the voices of modern-day Saudi women that the artist invited to recite a selection of verses. The selected poems were written by Arab poetesses from the pre-Islamic era up to the 12th century, and reflect the significant but scarcely documented tradition of women poetry in the Arab culture. They relay first-person expressions of longing, yearning, and pride penned by women who, in different eras and in different corners of the vast Arab region, found similar strength and empowerment in their bodies and audaciously reversed the male-dominated discourse of desire.

By interlacing geometric symbolism and poetic utterances, Awartani’s digital animation unleashes these powerful voices once again and orchestrates an intergenerational dialogue that subtly questions the status of women in contemporary society.

Listen to my words developed from a multimedia installation of the same title realized in 2018.

The artwork is commissioned by Thyssen-Bornemisza Art Contemporary (TBA21) and produced by NTU Centre for Contemporary Art Singapore for st_age.

Click here to view the full video.

COME, LET ME HEAL YOUR WOUNDS

2019

In this work titled, Come, let me heal your wounds. Let me mend your broken bones, as we stand here mourning, two major themes characterise this work: sustainability and cultural destruction. Natural herbs and spices have long been used for their medicinal qualities in South Asian and Arab cultures, and it is in Kerala where the fabrics in this artwork were made. The entire production process has sought to be ecologically and ethically conscientious; in doing so, it also becomes an act of resistance against the legacy of colonialism. As occupiers in India, the British were keen on industrialisation – the artist rejects this damaging legacy by working directly with the handloom industry.

About 50 herbs and spices – each with cultural references – were used to create these textiles, which not only encapsulate age-old knowledge, but also deem them healing cloths. Awartani first creates tears and holes in the fabric, in the locations where cultural destruction was committed by Islamic fundamentalist groups since the start of what is known as the Arab Spring in seven Arab nations – Saudi Arabia, Syria, Tunisia, Libya, Iraq, Egypt and Yemen. She then repairs all 355 holes through the process of darning.

There is no geographic correspondence to each panel; rather, together they are borderless representation of annihilated cultural heritage. In the face of ongoing destruction as well as polluting effects of big industries, the work is both a plea to safeguard ancient civilisation in the Arab world as well as a bid to recall and rejoice in the collective history of artisanship, the knowledge of healing plants, and the venerable tradition of repairing and revering objects.

Come, let me heal your wounds. Let me mend your broken bones, as we stand here mourning, 2019, Darning on medicinally dyed silk, 630 cm x 720 cm x 300 cm. © Dana Awartani

STANDING BY THE RUINS

2019

Dana Awartani created a site-specific installation at the Rottembourg Fort at the very edge of Rabat, where the land meets the sea. Inspired by the solitude, and to an extent the melancholy of this abandoned site that overlooks the vastness of the sea, the artist has created an installation that echoes the neglected and destroyed lands and built heritage of the Middle East and North Africa. Made to look like a traditional geometric tiled floor commonly found across the Muslim world and referencing the local craft of zellij, the work comprises of different soils that have been gathered from across Morocco and produced in collaboration with a zawiya of clay potters. Inspired by the ancient method of ‘adobe’ building, a method of architecture that uses earth and organic materials, and found around the world, the artist has produced the work mindfully skipping the crucial steps that temper and solidify the earth tiles. Instead, the work is allowed to crack, deteriorate and eventually crumble over the course of the exhibition, reflecting on the destruction of the Middle East’s built heritage. The work also encourages the viewers to witness, mourn and be active participants in the deterioration of the artwork, and see it evolve into new forms through every developing crack. The work questions the notion of time in relation to history, what societies choose to preserve, our collective memories and the importance-built heritage brings in unearthing our past in a way that creates a shared experience for the society inheriting this heritage and how it shapes notions of identity.

Installation shot of Standing by the Ruins at the Rabat Biennale 2019. Compressed earth, 450 cm x 1130 cm. © Dana Awartani

WHEN FIRE LOVES WATER

2019

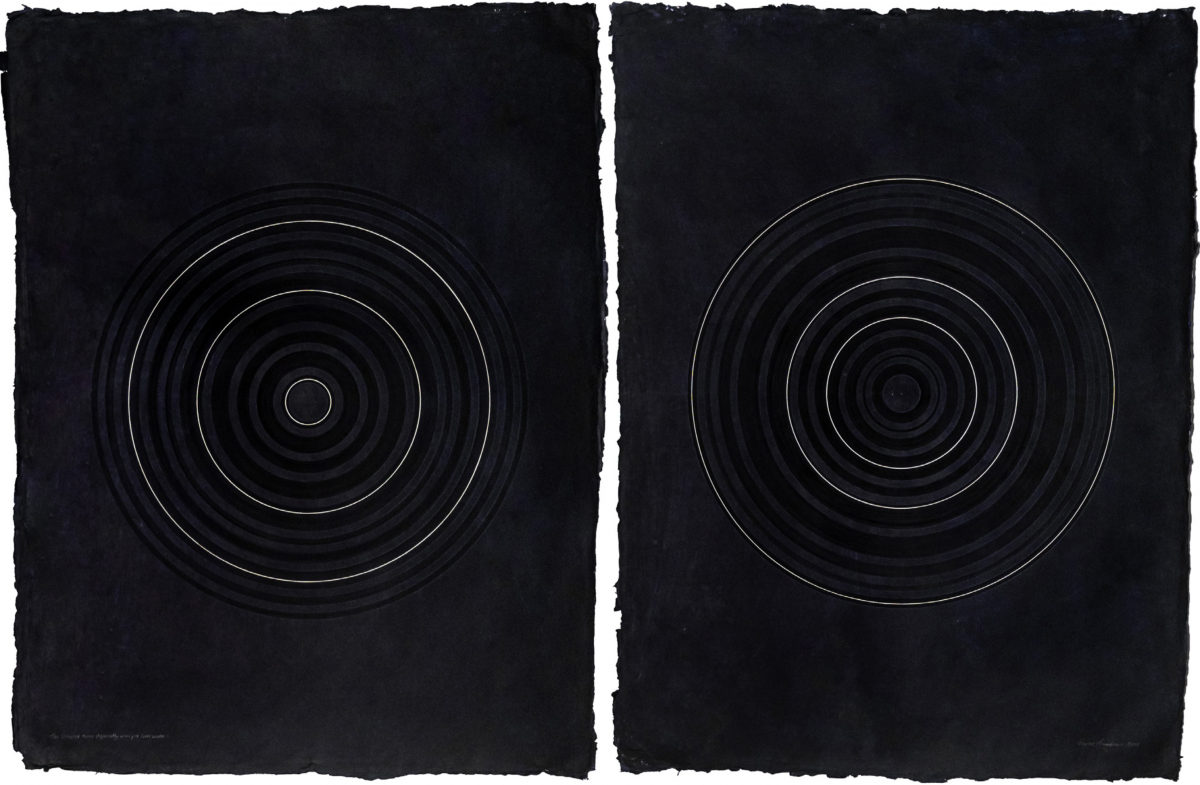

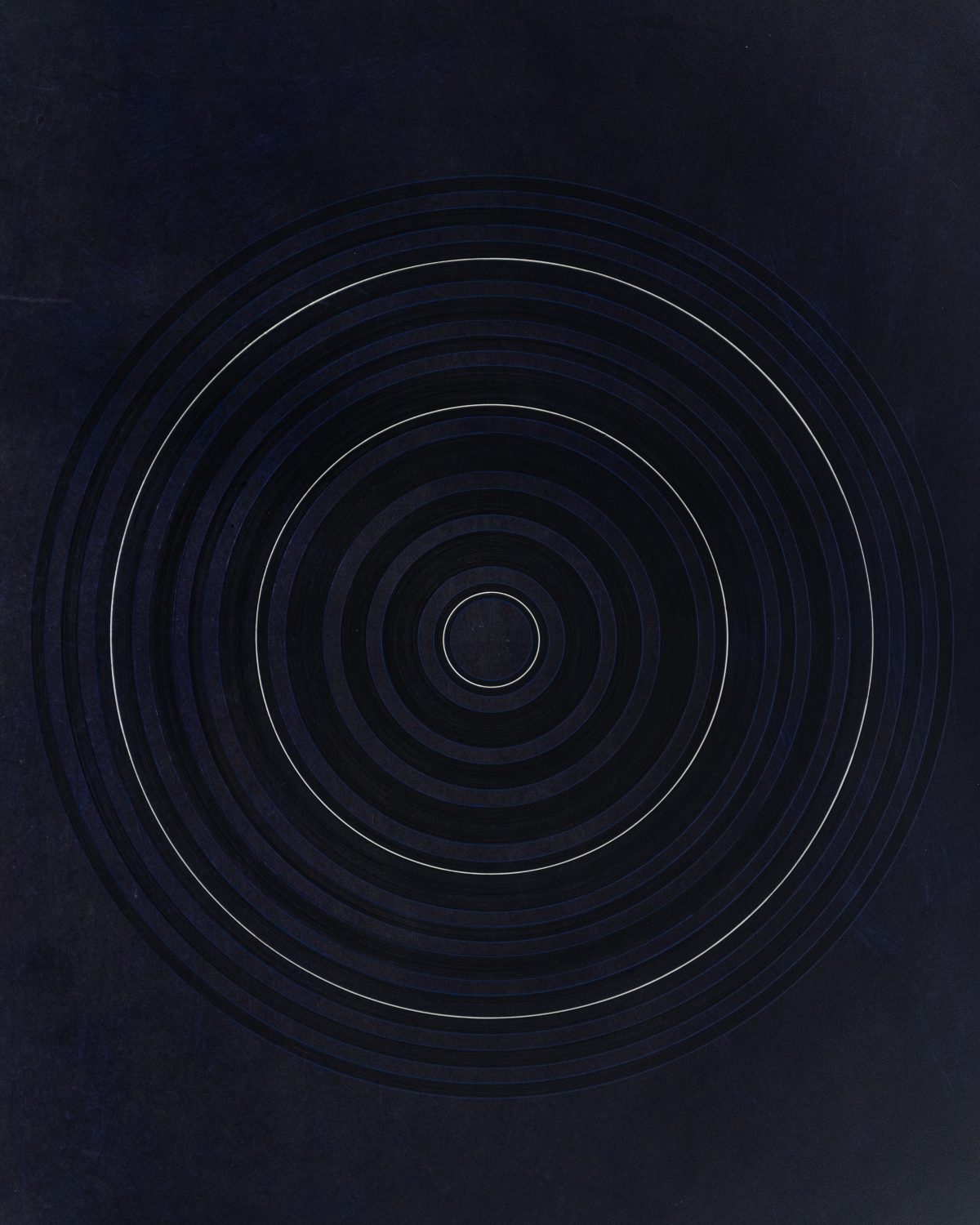

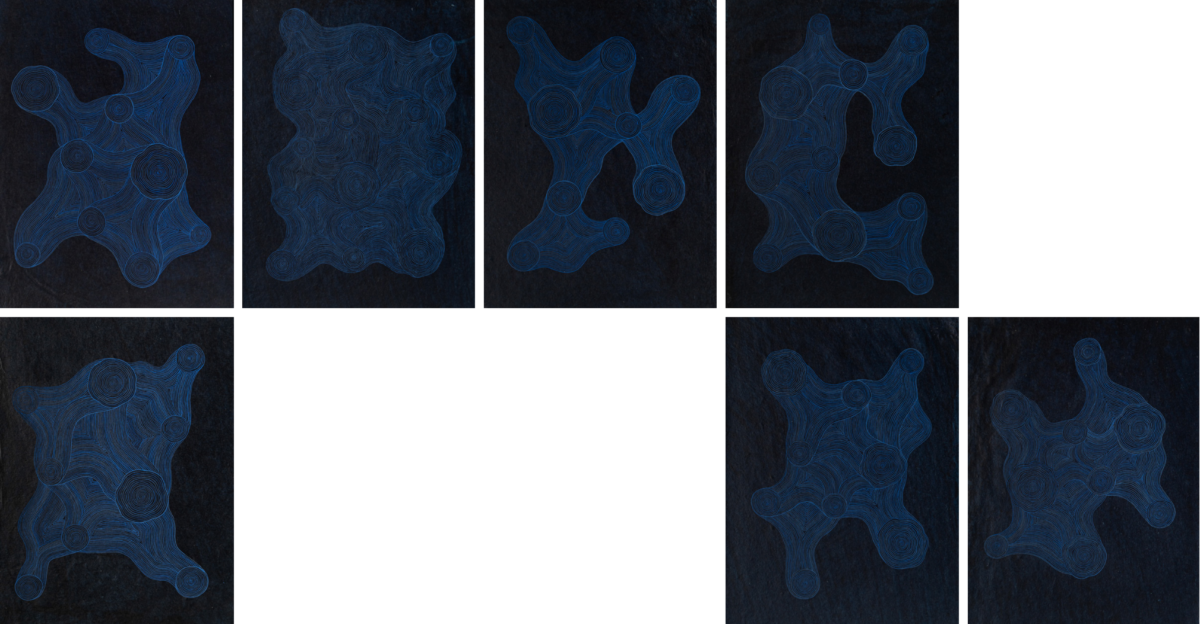

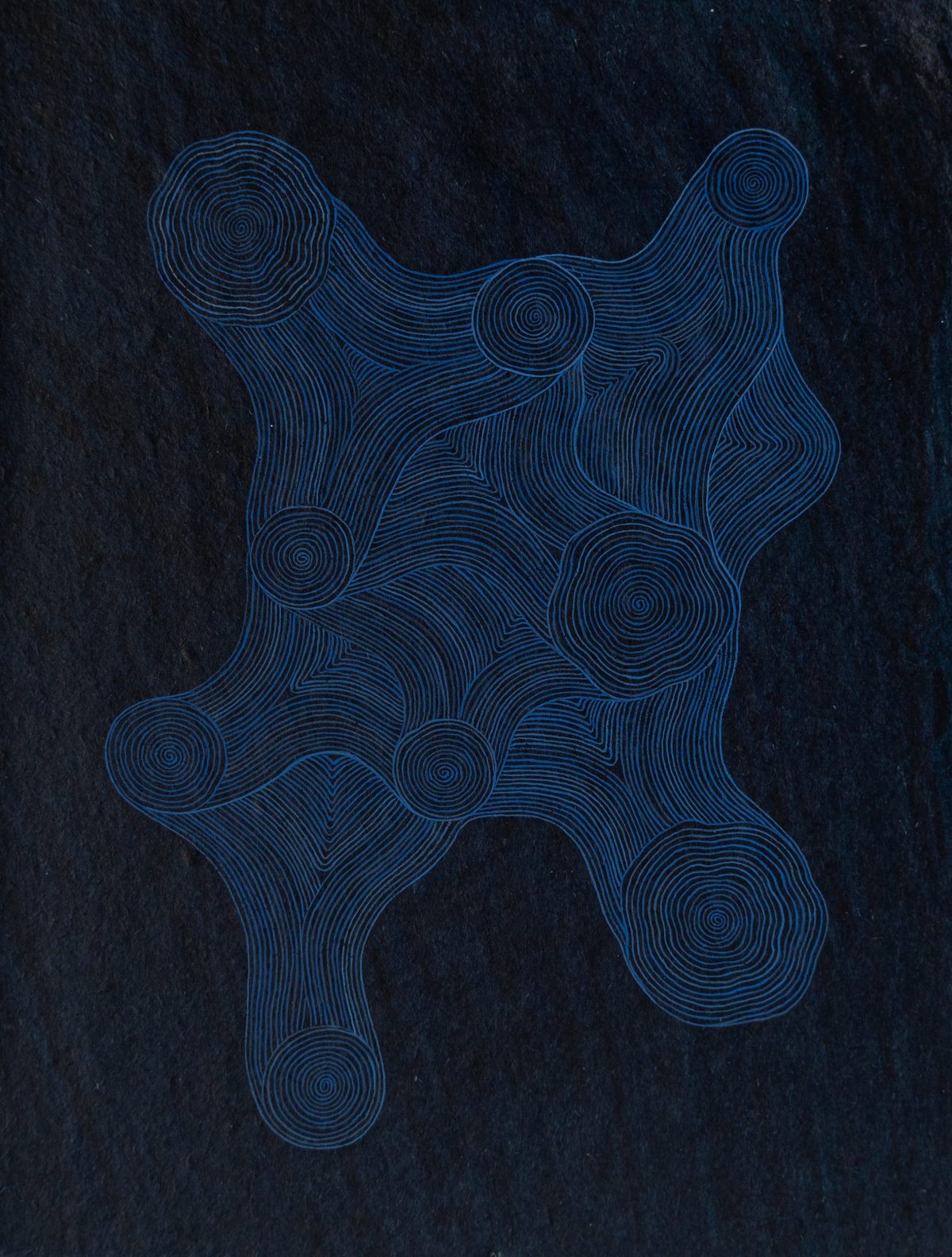

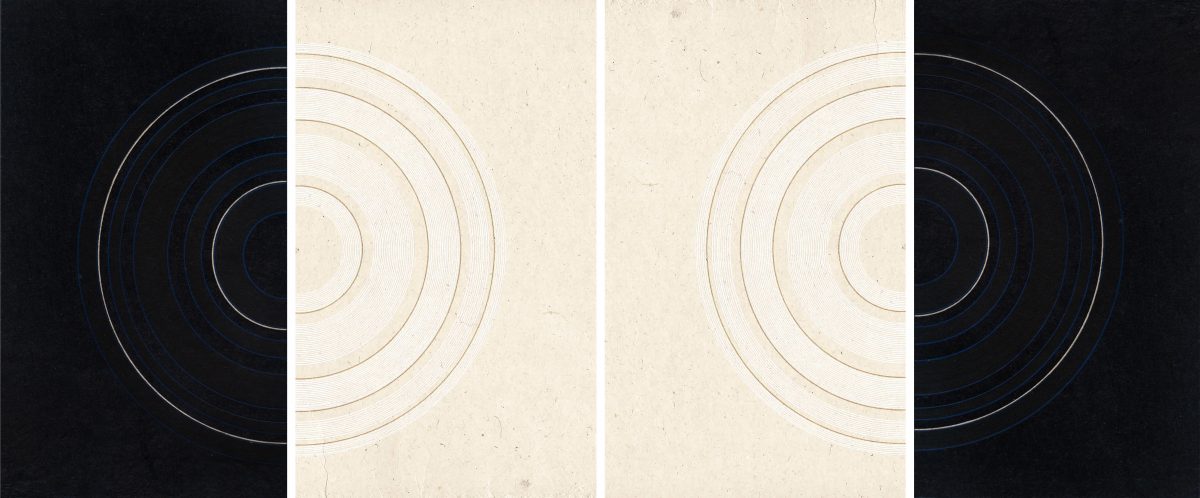

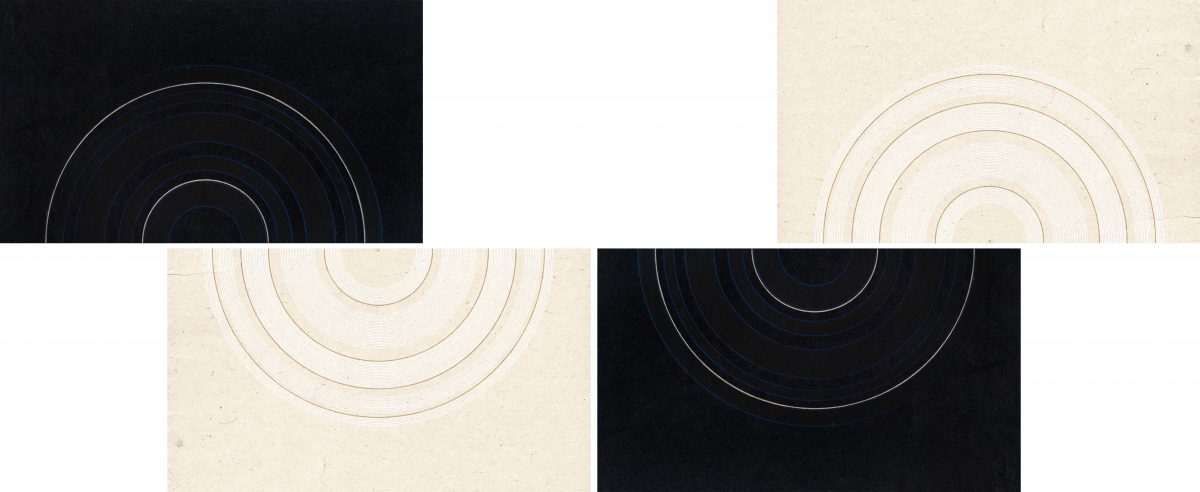

Awartani’s ‘When Fire Loves Water’ series, act as moments of pause and reflection within her practice. In contrast to her usual highly intricate paintings, this minimalist and monochromatic body of work revert back to the source of her inspiration, Sufi mysticism. Awartani describes these paintings as acts of mediation and moments of contemplation as part of her daily rigour of being an artist, a method she frequently adopts to quiet the mind.

Created on handmade paper that recycles left over fibbers from textile mills, these paintings draw upon multiple facets of her work, most importantly the role of sacred geometry as a visual language. In this case, Awartani explores the symbolism of the circle as a source and expression of Tawhid, as all of her drawings begin and finish within a circle expressing the multiplicity within singularity. By choosing to revert back to the purity of the circle, she reflects on the simple act of conscious re-enactment as a form of introspection.

Works such as In Search of Silence, aim to expand beyond the formal limits of traditional miniature painting technique and explore new languages of expression, one that is more fluid, spontaneous and unrestrained. In The Union of Fire and Water, which brings two different temporalities together, Awartani takes a playful approach by encouraging the viewers to actively participate in the layout of the paintings.

You Are The Universe in Ecstatic Motion I, 2019, Gouache and shell gold on handmade paper, 155 x 148cm. © Dana Awartani

When Fire Loves Water, 2019, Gouache and shell gold on handmade paper, 185 x 122cm. © Dana Awartani

In Search of Silence, 2019, Gouache on handmade paper, 7 pieces – 21.7 x 26.7 cm each. © Dana Awartani

The Union of Fire and Water I & II, 2019, Gouache and shell gold on handmade paper, 4 pieces – 28.5 x 17 cm each. © Dana Awartani

LISTEN TO MY WORDS

2018

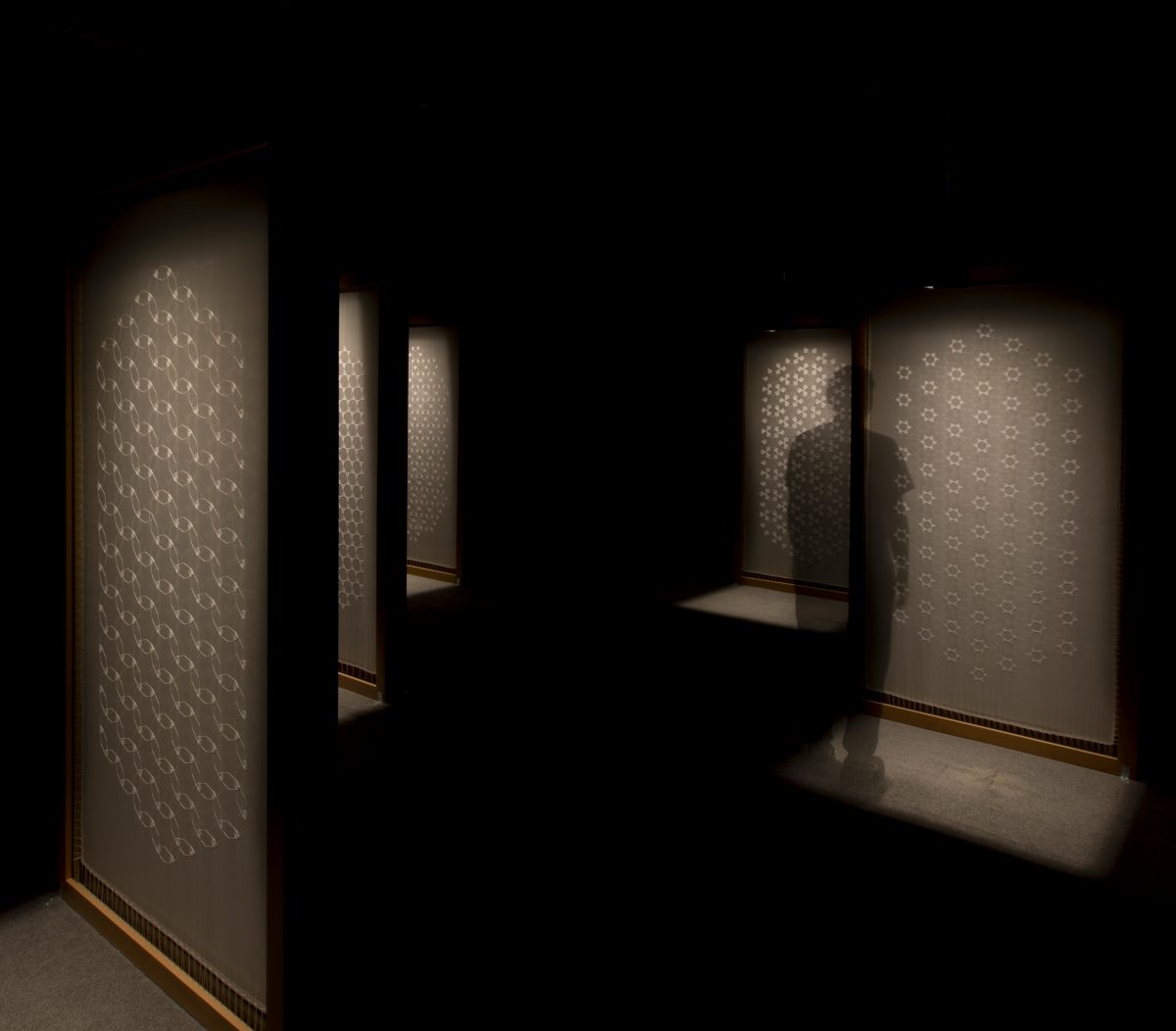

Listen to My Words presents an immersive installation that combines hand embroidered silk panels with moving voices of women reciting poetry. It draws from an overlooked and still limitedly documented tradition of female poets in the Islamic world, including poems from the pre-Islamic times through the 12th century. The poems and poetesses hail from a wide range of cultures within the Arab world and explore the themes of love and longing which are also generally considered taboo subjects.

The presence of geometric layered panels throughout this work references the ‘Jali’ screen, which is characteristic of the Islamic tradition and more specifically in this piece, Mughal India, and they were typically used to shield and protect women from the male gaze. In this case the artist has reinvented these screens by using embroidery in collaboration with craftsman in India, and has chosen a specific stitch called ‘Aari’ which derived from the Mughal period. Awartani was more specifically inspired by a figure named Nourjehan who was the wife of a Mughal Emperor and she partook a leading yet hidden role in governing the state while being forced to sit behind a Jali screen, whispering commands into her husband’s ear.

The work juxtaposes theory and execution, as the space is one that evokes serenity and contemplation interjected with radical words within the space. The recitation of the poetry is done in its original language of Arabic, using the voices of modern day Saudi women who embody the spirits of these forgotten poetesses, strong, empowered and inspirational.

With special thanks to: Sara Abdu, Fatima Al Banawi, Najla Al Bassam, Ahd Kamel and Zahar Al Sayed.

Listen to my Words, 2018, 7 panels of hand embroidery on silk and sound installation, various sizes. © Dana Awartani

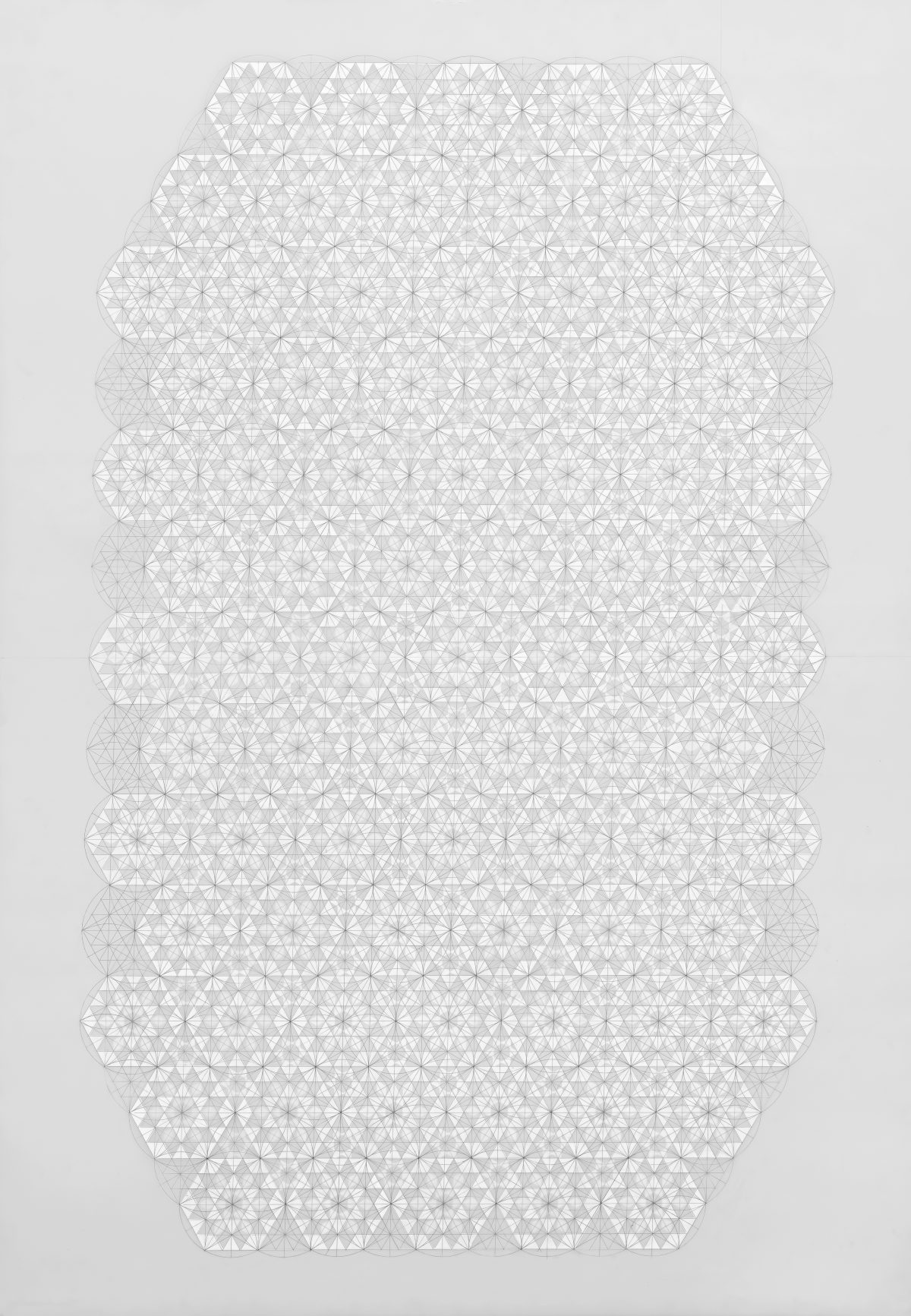

JALI

2018

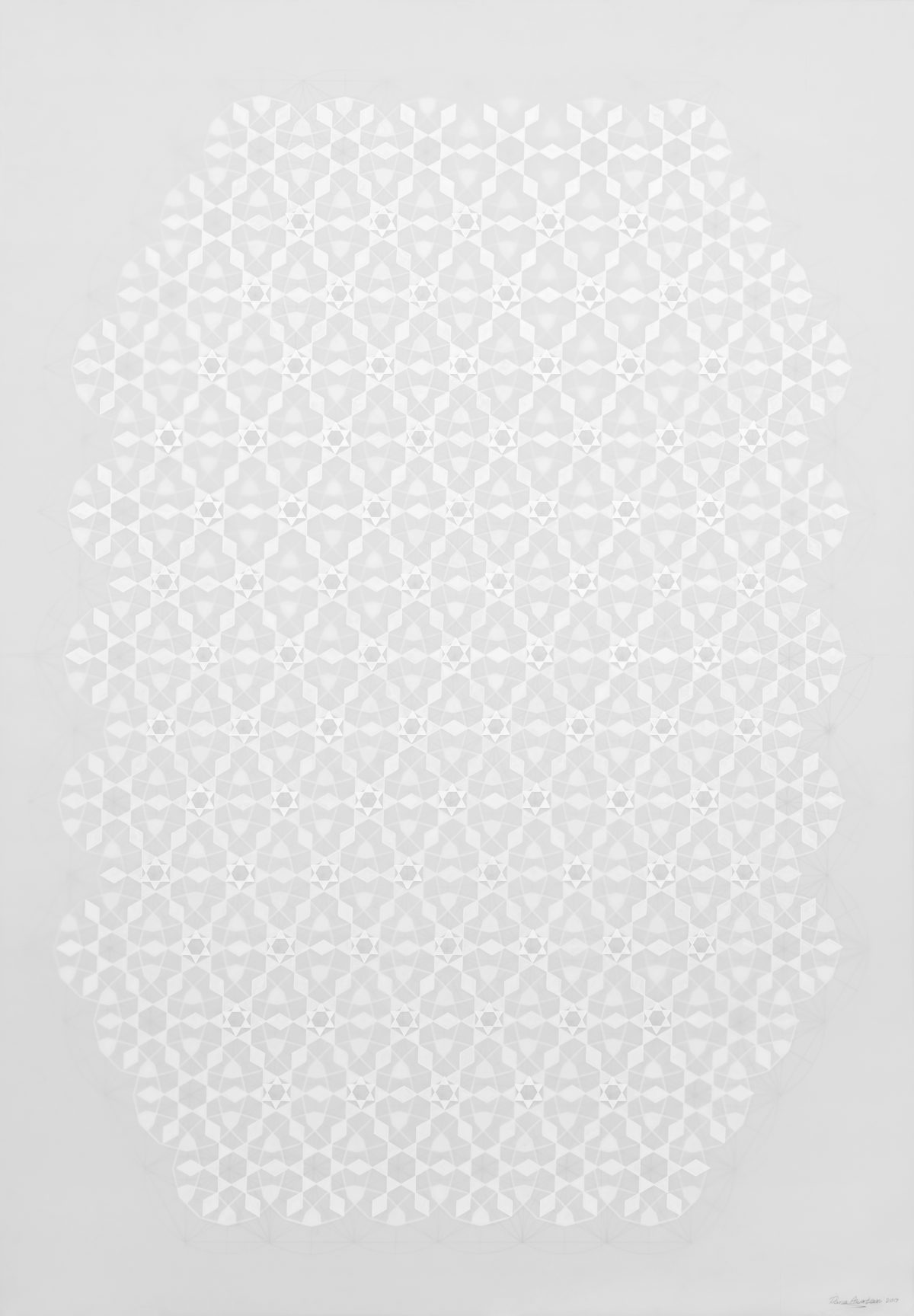

Dana Awartani’s Jalis are a prelude to her immersive installation Listen to my Words, which consists of hand embroidered silk Jalis (screens) and an audible element of women reciting poetry.

The use of geometric layered panels references a Mughal style of the ‘mashrabiya’, as well as a leading female figure, Nourjehan, who has inspired the piece. Fabled to have whispered commands into her husband the emperor’s ears, she played a pivotal yet hidden role in governance. The Mashrabiya, typically used in architectural structures to shield and protect women from the male gaze, is here reinvented by layering three white panels creating a larger, wholistic design. The color white references a Jali-typically made using stone or white marble, as well as serves to enhance the essential interplay of light on the physical and metaphorical depths of the piece.

Jali seeks to both lift a veil on a cast of forgotten radical female poets ranging from pre-Islamic times to the 12th century, as well as examines and questions the duality of public and private domains, the metaphor of light and shadow, and explores the spiritual Islamic qualities of zahir (outward dimension) and batin (inward dimension).

Front and back view of Jali 1, 2018, gouache on drafting film (3 layers), 120 x 84 cm. © Dana Awartani

Front and back view of Jali 2, 2018, gouache on drafting film (3 layers), 120 x 84 cm © Dana Awartani

Front and back view of Jali 3, 2018, gouache on drafting film (3 layers), 120 x 84 cm © Dana Awartani

Front and back view of Jali 4, 2018, gouache on drafting film (3 layers), 120 x 84 cm © Dana Awartani

Front and back view of Jali 5, 2018, gouache on drafting film (3 layers), 120 x 84 cm © Dana Awartani

I WENT AWAY AND FORGOT YOU

2017

Dana Awartaniʼs mixed media installation, I Went Away and Forgot You. A While Ago I Remembered. I Remembered Iʼd Forgotten You. I Was Dreaming, is a call to celebrate the beauty of traditional Islamic design and architecture, and offers up a ritual that involves construction and destruction.

Awartani has meticulously assembled over a number of days a large and immaculate geometric floor design made with locally sourced sand which the artist has previously dyed herself using natural pigments that derive from stones and plants, staying true to her appreciation for traditional techniques of making art. The pattern she created is also shaped on the traditional Islamic tile work, once common in most Arab and Islamic homes.

The video work was created by Awartani once she had completed the installation on the floor of an old abandoned house, located in the old part of Jeddah, where the artist’s grandparent’s generation used to live. It shows her destroying the art work by sweeping up the sand tiles as a symbolic commentary on the modern-day destruction of our cultural identity and heritage, which has been a result of a carless and an obsessive need for a more modernized and industrial society without the conscious awareness of what we are leaving behind. With this final gesture, the artist aims to highlight the importance of preserving and cherishing what in essence is a crucial part of the collective identity in the region, not as an attack on modernization, but rather pointing out the importance of the old and new co-existing and living together side by side.

The house that the artist has chosen to create the piece plays a crucial role in the artwork, as the building was a typical home amongst the wealthy local elite during the late 50ʼs and early 60ʼs, and it was during this time that buildings in Jeddah broke from traditional Hejazi architecture and adopted a more European aesthetic, imbued with forward looking notions of “civilization” modelled on a western ideal, and in turn completely abandoning their own cultural identity.

Awartaniʼs symbolism extends from what lies on the floor and what is projected on the wall that come together as a cautionary tale, contemplating the duality of creation and destruction, past and present. The artist seeks to raise awareness about the importance of celebrating and preserving the timeless language of geometric aesthetics as a universal language of beauty and harmony.

I Went Away and Forgot You. A While Ago I Remembered. I Remembered Iʼd Forgotten You. I Was Dreaming, 2017, Mixed media installation with sand and natural pigments, single-channel video, with no sound, 22 minutes. © Dana Awartani

Installation shot of I Went Away and Forgot You. A While Ago I Remembered. I Remembered Iʼd Forgotten You. I Was Dreaming, at Franco Noero gallery, Turin, Italy. © Dana Awartani

LOVE IS MY LAW LOVE IS MY FAITH

2016

Love is my Law, Love is my Faith is inspired by the eight love poems by Ibn Arabi, a 12th century Sufi mystic, poet and philosopher. Known as the taj al- rasa il wa-minhaj al-was il, these particular writings are considered some of the best love poems in Islamic history, outlining the nature of divine love and the perfect believer from a range of perspectives. He was inspired to write them while in Mecca, staring at the Ka’ba and was overcome by the presence of God. He felt the Ka’ba ask him to make the tawaf, the circumambulation around it, and the Zamzam ask for him to drink from it and he was afraid of this feeling of directly having the eyes of God upon him. But in this fear he felt love, an unusual kind of love. As he stood, staring at this being of stone, he thought of how it stood as an intermediary between the human and the divine. He went away and wrote these poems addressed to the Ka’ba and God, in order to express this knowledge of their divine realties.

Awartani has responded to this literature by creating eight hanging embroidery panels. They are intricate and meticulously patterned, hand embroidered by textile craftsmen in India, steeped in the study of mathematics. The patterns themselves come from the traditions of sacred geometry and the artist uses them to create genealogies of meaning that act as a form of meditation, praying contemplation and search for the inner spirit rather than outer. When hanging they create a perfect cube but are truly activated by light cascading through the stepped layers, carving out a meditative inner expression.

As you view her geometric embroidered panels you are on the inside of an aesthetic experience yourself, one that shares with us a form of love. This is a kind of depiction rooted in historical practice, and in the rendering of the infinite it reflects Qur’anic and divine perfection.

Installation shot of Love is my Law, Love is my Faith and the Kochi Muziris Biennale, 2016. Hand embroidery on fabric, 200 x 200 x 200 cm. © Dana Awartani

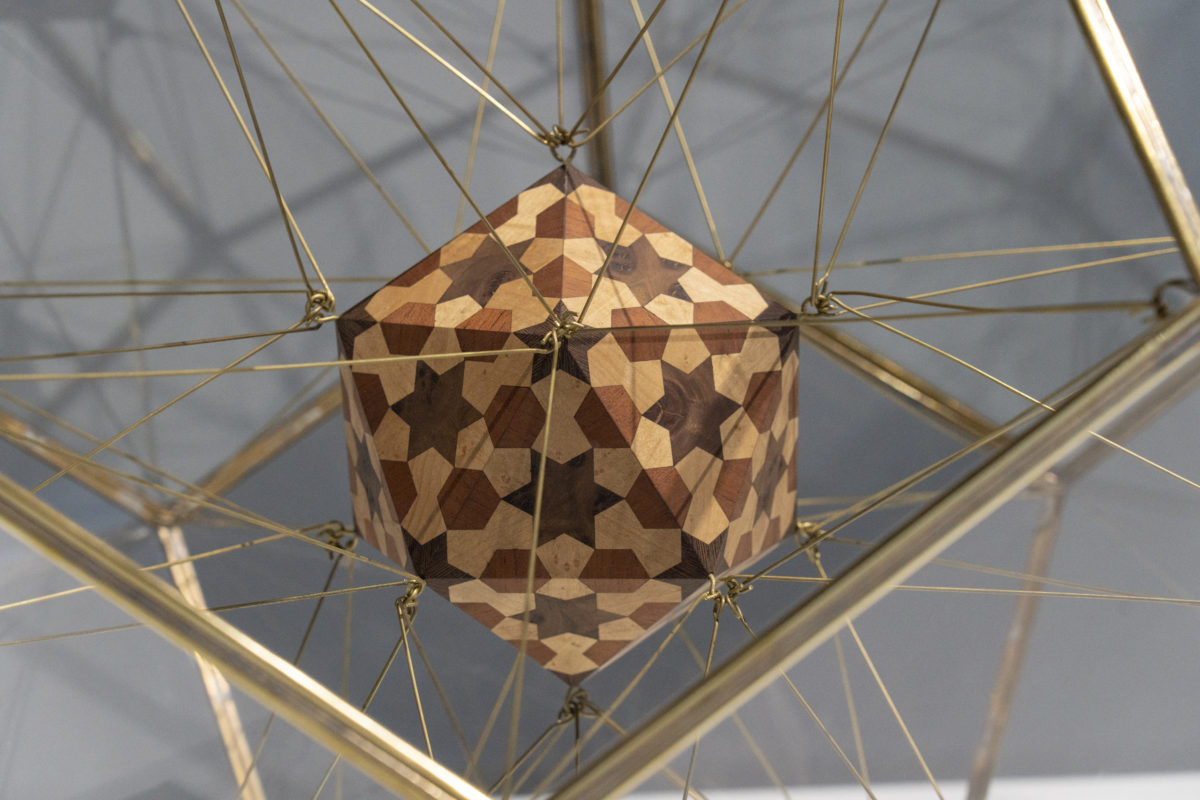

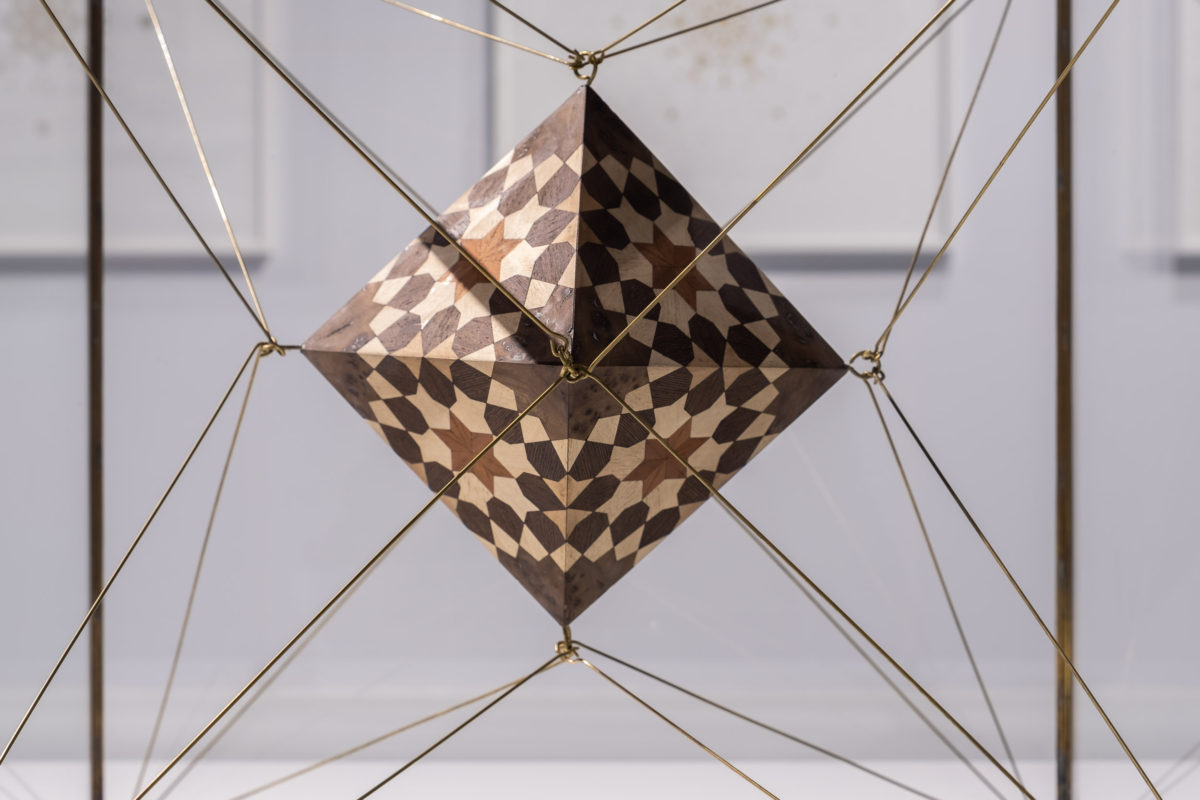

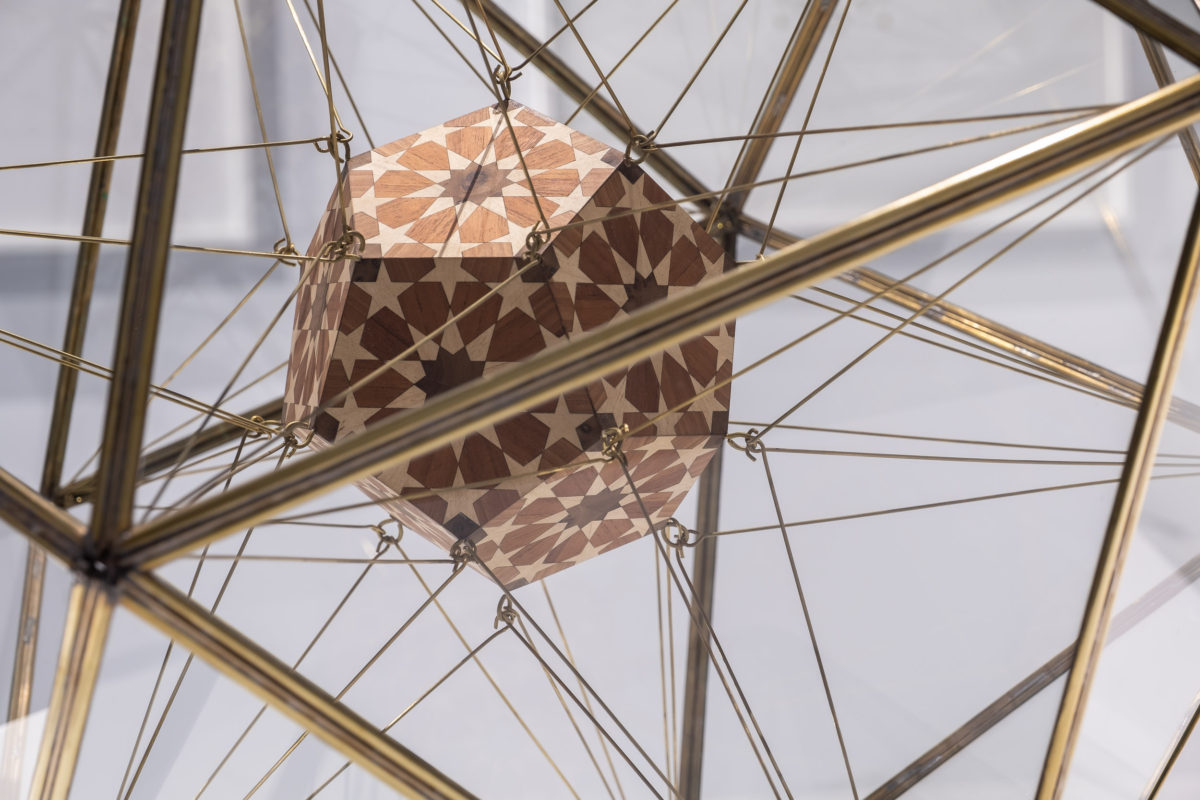

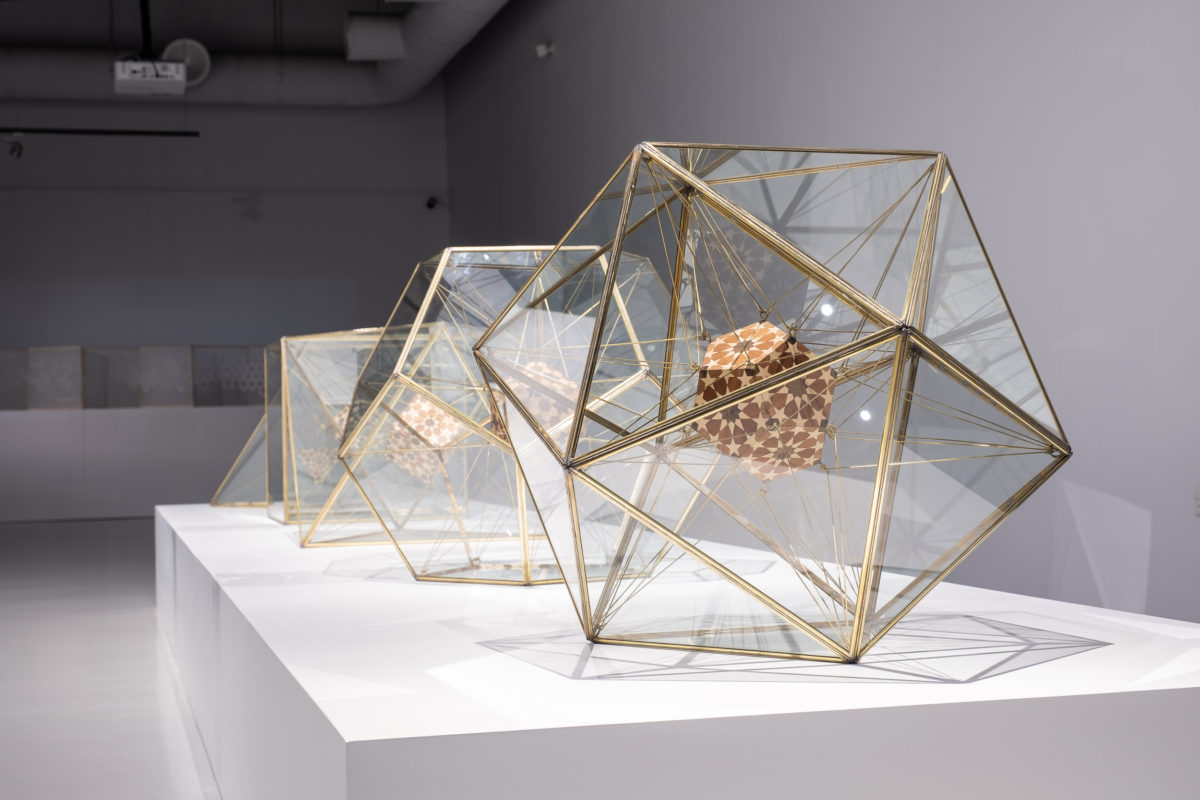

PLATONIC SOLID DUALS

2016 – 2018

The platonic solids are the most frequently studied shapes in history. For thousands of years, geometers have studied their mathematical properties and have been fascinated by their inherent beauty and symmetry. What makes them particularly important is that they are considered as the only five ‘perfect’ shapes in three-dimensional space that derive from a sphere. They appear the same from any vertex, their faces are made of the same regular shape, and their vertices represent the most symmetrical distribution of the numbers four, six, eight, twelve and twenty within a sphere.

Awartani has taken direct inspiration from these forms and has translated these three-dimensional shapes into five sculptures that examine the dual properties that these shapes share, as each polyhedron has a dual or ‘polar’ polyhedron with faces and vertices interchanged, which is also known as polar reciprocation. By this duality principle each platonic solid has a pair that fits within each other in geometric harmony.

In her rendering, she has worked with craftsmen in India and created the core shapes in wood, applying her own unique visual language of sacred geometry through traditional woodworking techniques. These shapes in their perfection had also been attributed to the five classical elements (earth, air, fire, water, aether) by Plato, and the wood is a tie to this being the only substance that needs all elements to survive in nature.

The patterning and technique not only give a fresh perspective, but also emphasizes the relevance that these shapes have played in Islamic art, as Euclidean geometry can be seen as the source or main principle that sacred geometry was built upon within the Islamic tradition.

The Platonic Solid Duals series, 2019, Wood, copper and brass, various sizes. © Dana Awartani

Tetrahedron Within a Tetrahedron II from The Platonic Solid Duals series, 2019, Wood, copper and brass, 121 x 100.2 x 100.2cm. © Dana Awartani

Octahedron Within a Cube II from The Platonic Solid Duals series, 2019, Wood, copper and brass, 121 x 100.2 x 100.2cm. © Dana Awartani

Cube Within an Octahedron II from The Platonic Solid Duals series, 2019, Wood, copper and brass, 121 x 100.2 x 100.2cm. © Dana Awartani

Icosahedron Within a Dodecahedron II from The Platonic Solid Duals series, 2019, Wood, copper and brass, 121 x 100.2 x 100.2cm. © Dana Awartani

Dodecahedron Within an Icosahedron II from The Platonic Solid Duals series, 2019, Wood, copper and brass, 121 x 100.2 x 100.2cm. © Dana Awartani

PLATONIC SOLID DUALS

2017

Tetrahedron Within a Tetrahedron II from the Platonic solid Duals series, 2017, shell gold and ink on paper, 100 cm x 100 cm. © Dana Awartani

Octahedron Within a Cube II from the Platonic solid Duals series, 2017, shell gold and ink on paper, 100 cm x 100 cm. © Dana Awartani

Cube Within an Octahedron II from the Platonic solid Duals series, 2017, shell gold and ink on paper, 100 cm x 100 cm. © Dana Awartani

Dodecahedron Within an Icosahedron II from the Platonic solid Duals series, 2017, shell gold and ink on paper, 100 cm x 100 cm. © Dana Awartani

Icosahedron Within a Dodecahedron II from the Platonic solid Duals series, 2017, shell gold and ink on paper, 100 cm x 100 cm. © Dana Awartani

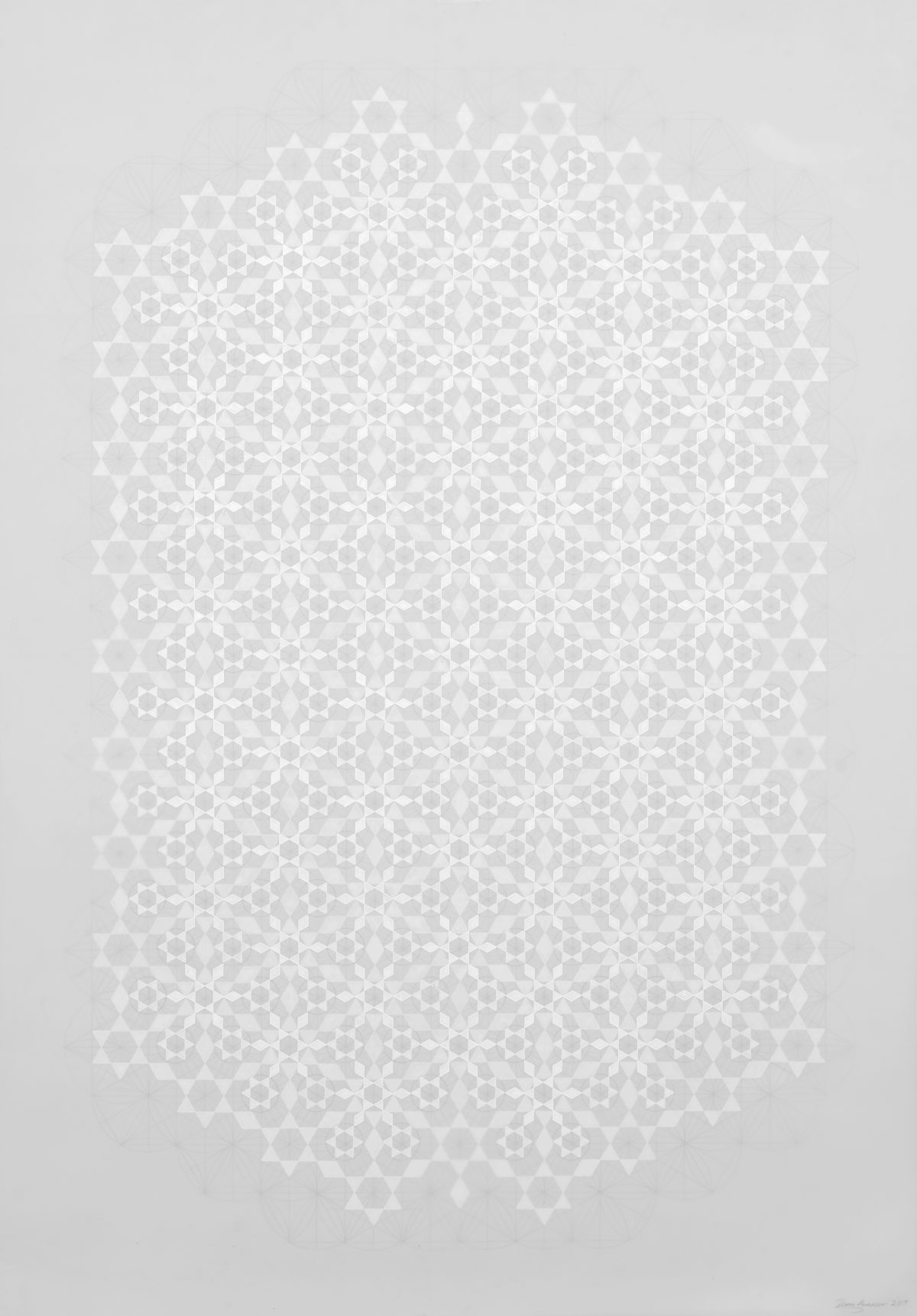

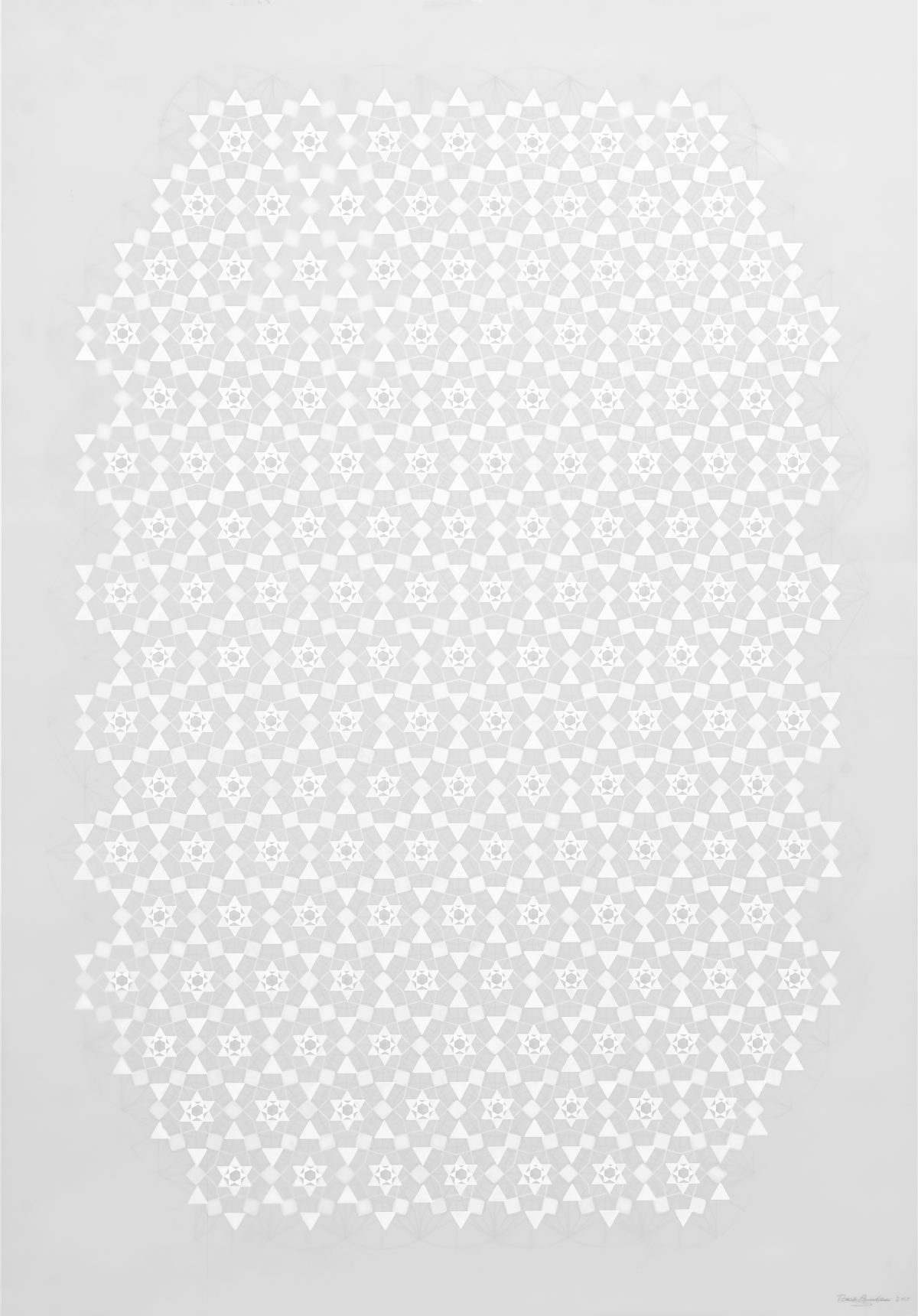

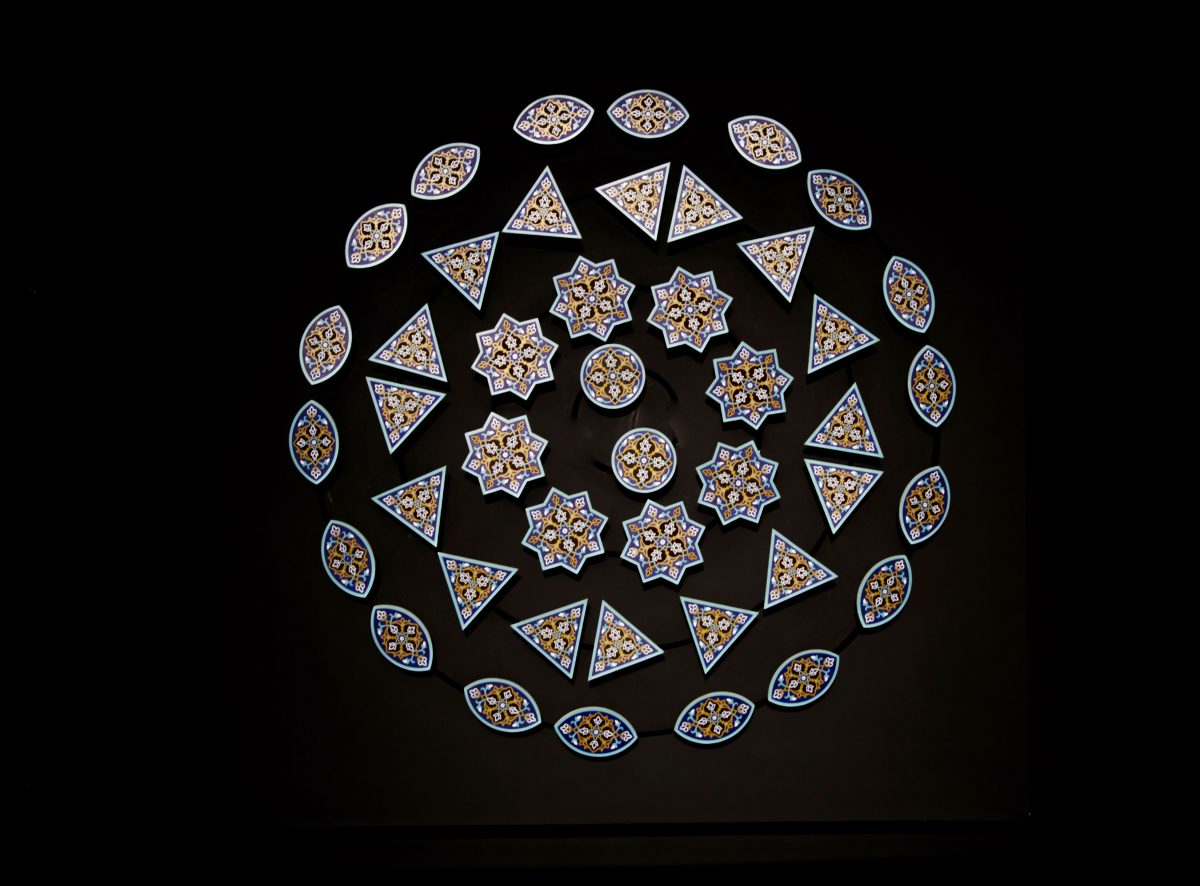

IT IS HE WHO CREATED YOU FROM A SINGLE SOUL

2016

Commissioned specifically for the Take Me (I’m Yours) exhibition held at the Jewish Museum in New York. The presentation builds upon an iconic exhibition of the same name that took place in 1995 at the Serpentine Gallery in London. Conceived by the curator Hans Ulrich Obrist and the artist Christian Boltanski, which aims to create a democratic space for all visitors to take ownership of artworks, and curate their personal art collections, by subverting the usual politics of value, consumerism, and the museum experience. This highly unconventional exhibition encourages visitors to participate, touch, and even take-home works of art by 42 international and intergenerational artists, many of whom created new and site-specific works for the exhibition.

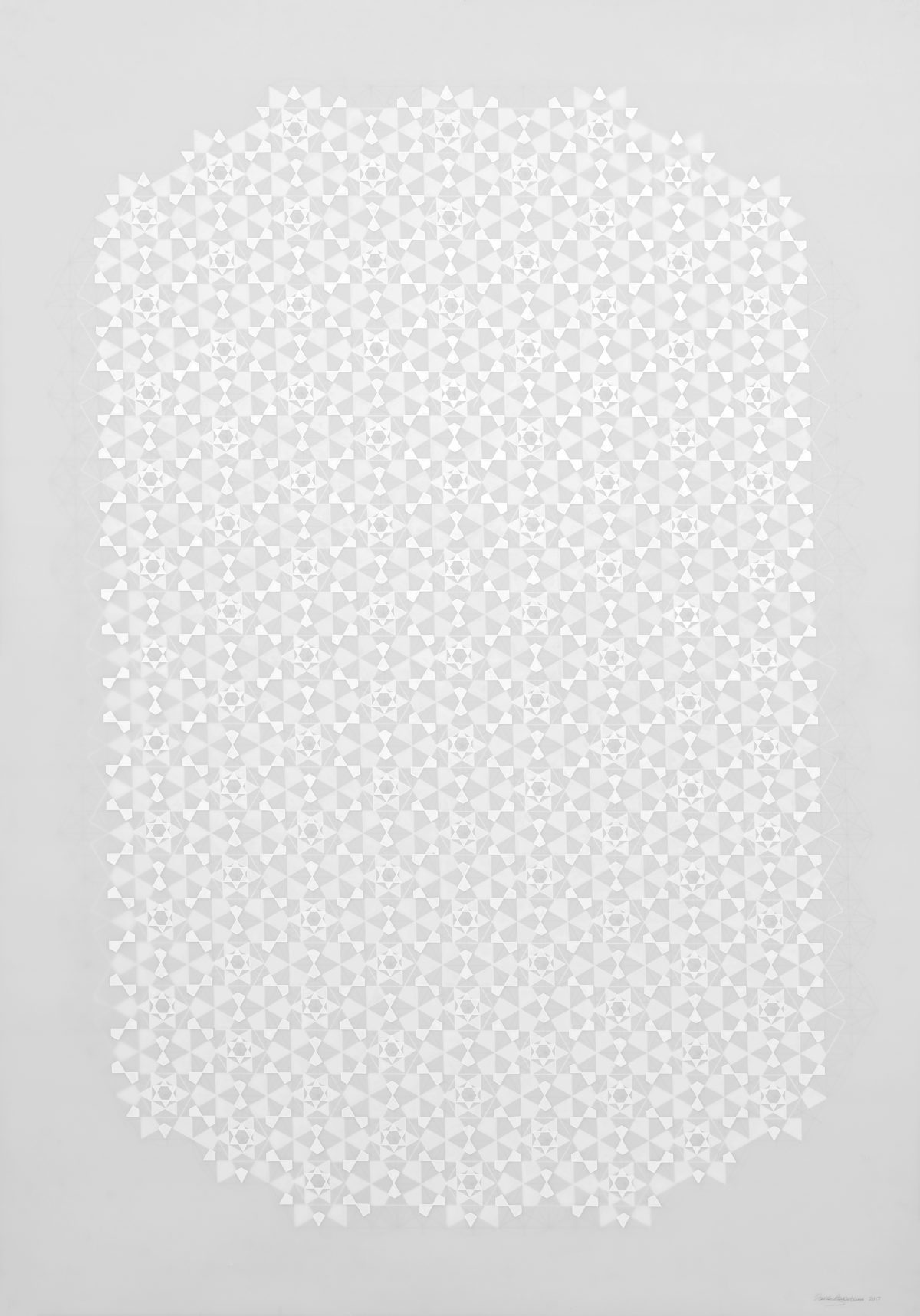

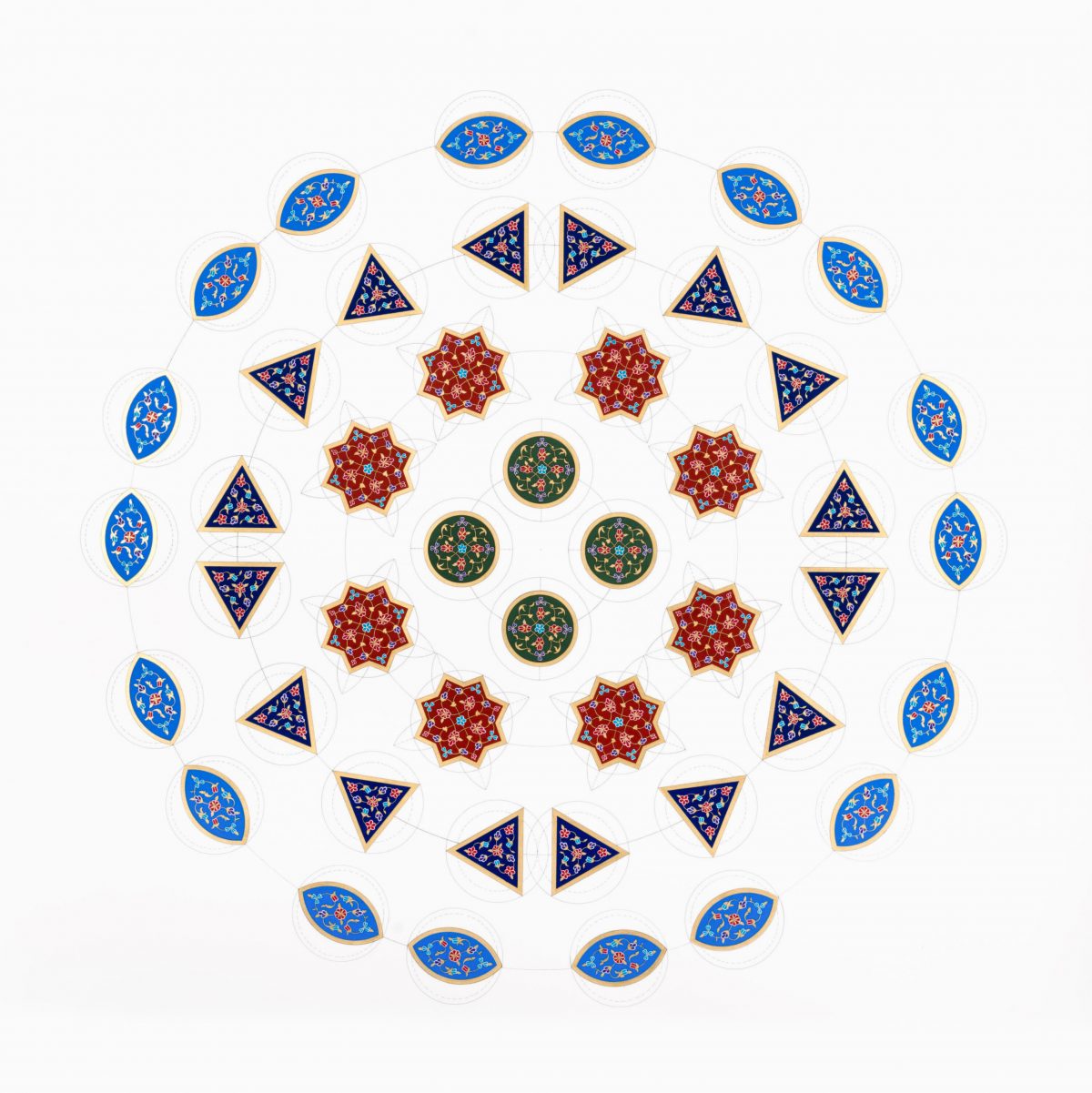

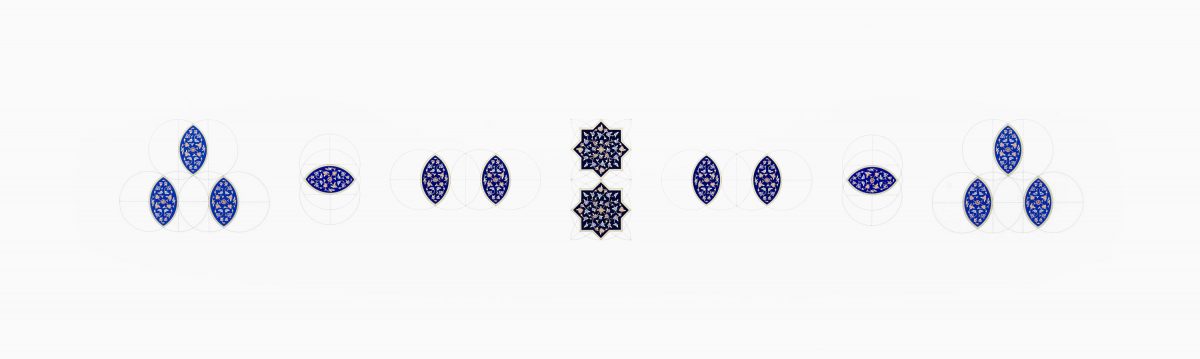

Awartani’s commissioned art work, It is He who Created You from a Single Soul, is a playful approach to the Israeli occupation of Palestine, encouraging viewers to question the ideas of meaning making through symbols, collective ownership and belonging.

The six-pointed star, more commonly known as the Star of David, which has been adopted as the symbol for the Zionist movement and in more recent history, in 1948 on the flag of the founding of the state of Israel, holds deeply negative connotations in the Arab world. However historically it has always been a shared sacred symbol that has been present throughout all the monotheistic religions and beyond but has been forgotten and turned into a symbol that is deeply taboo in various cultures. Ironically it can be found adorning numerous mosques and monuments throughout the Islamic world, but most importantly it can be found covering the complete exterior of the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem, which is the third holiest site within the Islamic faith. The artwork Awartani has created are replica paper tiles like the ones found on the Dome of the Rock, encouraging the audience to own a piece from a location that has been a focal point for religious wars for thousands of years, with one religion claiming it to be more significant to them then another, whereas the work exhibited within the context of the Jewish Museum aims to encourage the idea of a shared sacredness and coexistence that belongs to everyone yet to no one

Installation shot of It is He who Created You from a Single Soul at the Jewish Museum, New York, 2016. Printed card paper, 29.7 x 42 each. © Dana Awartani

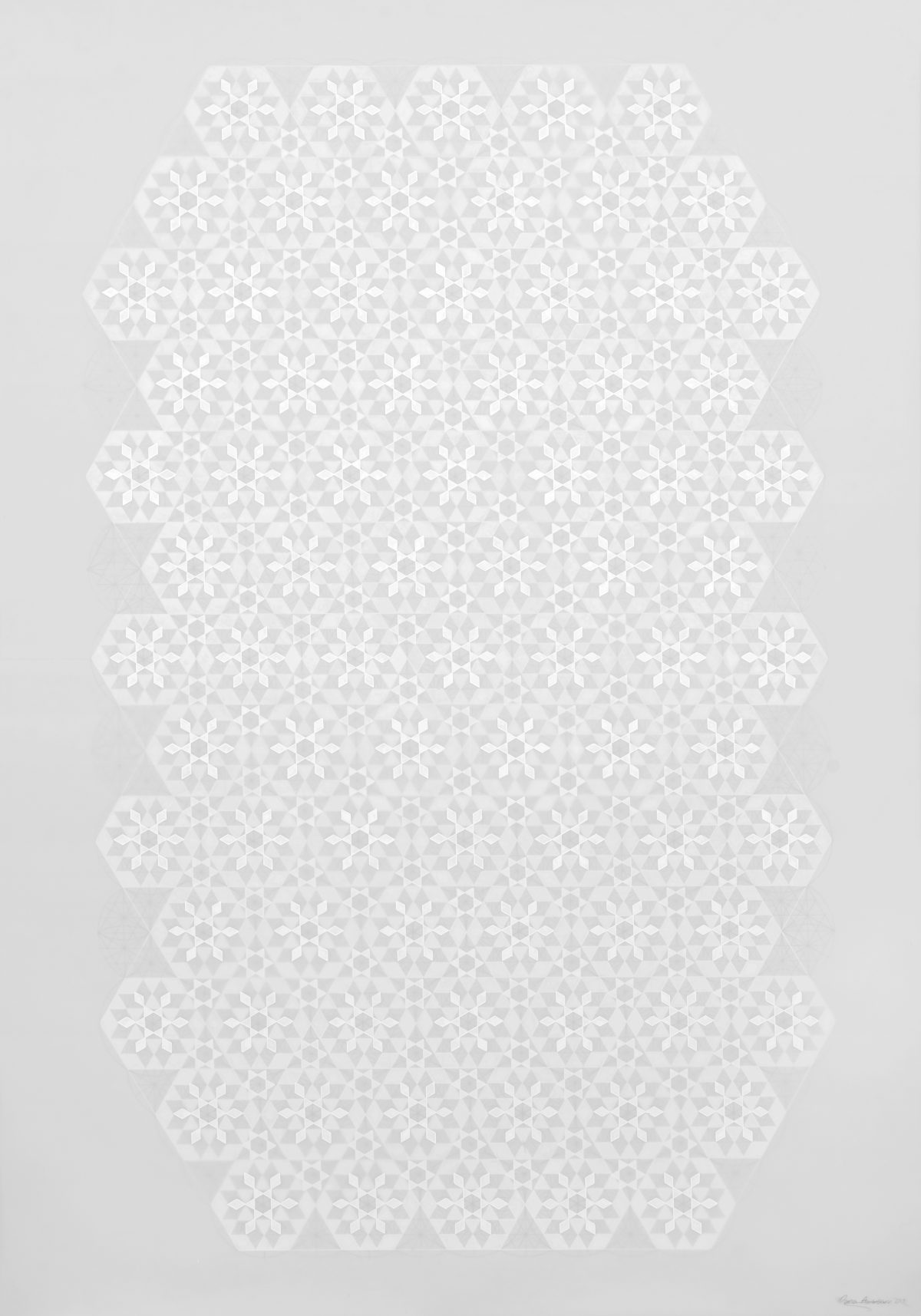

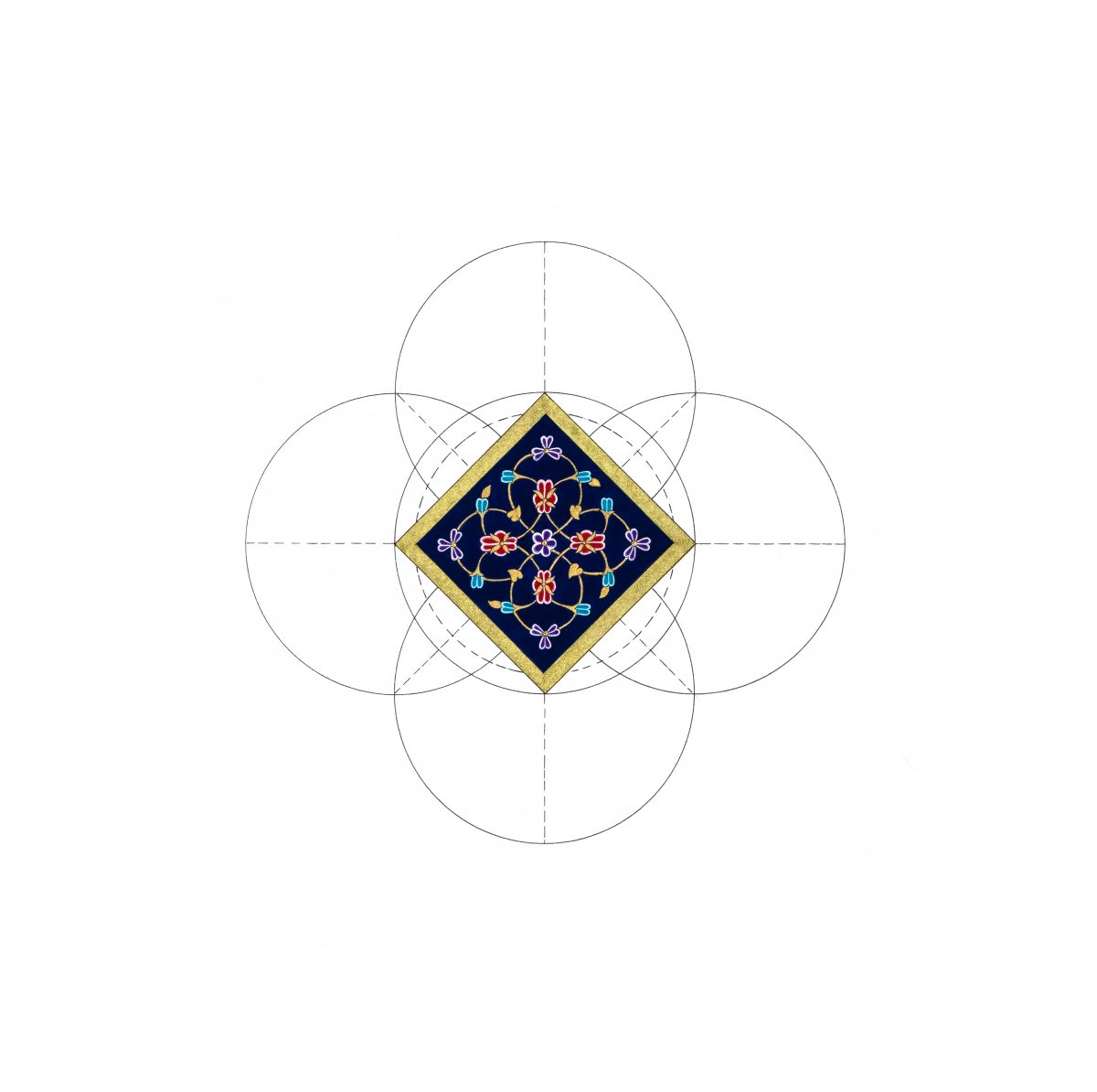

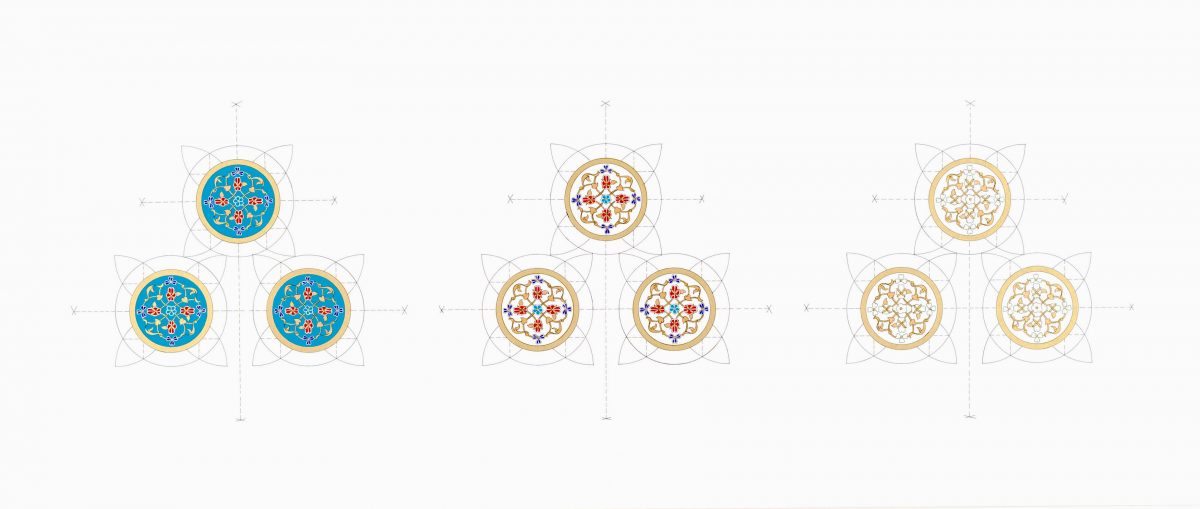

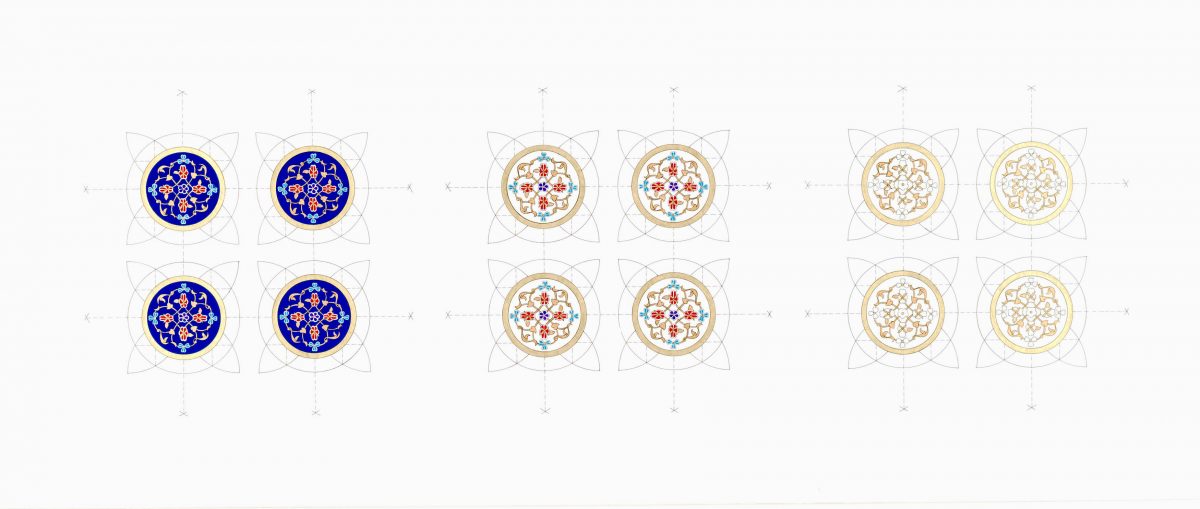

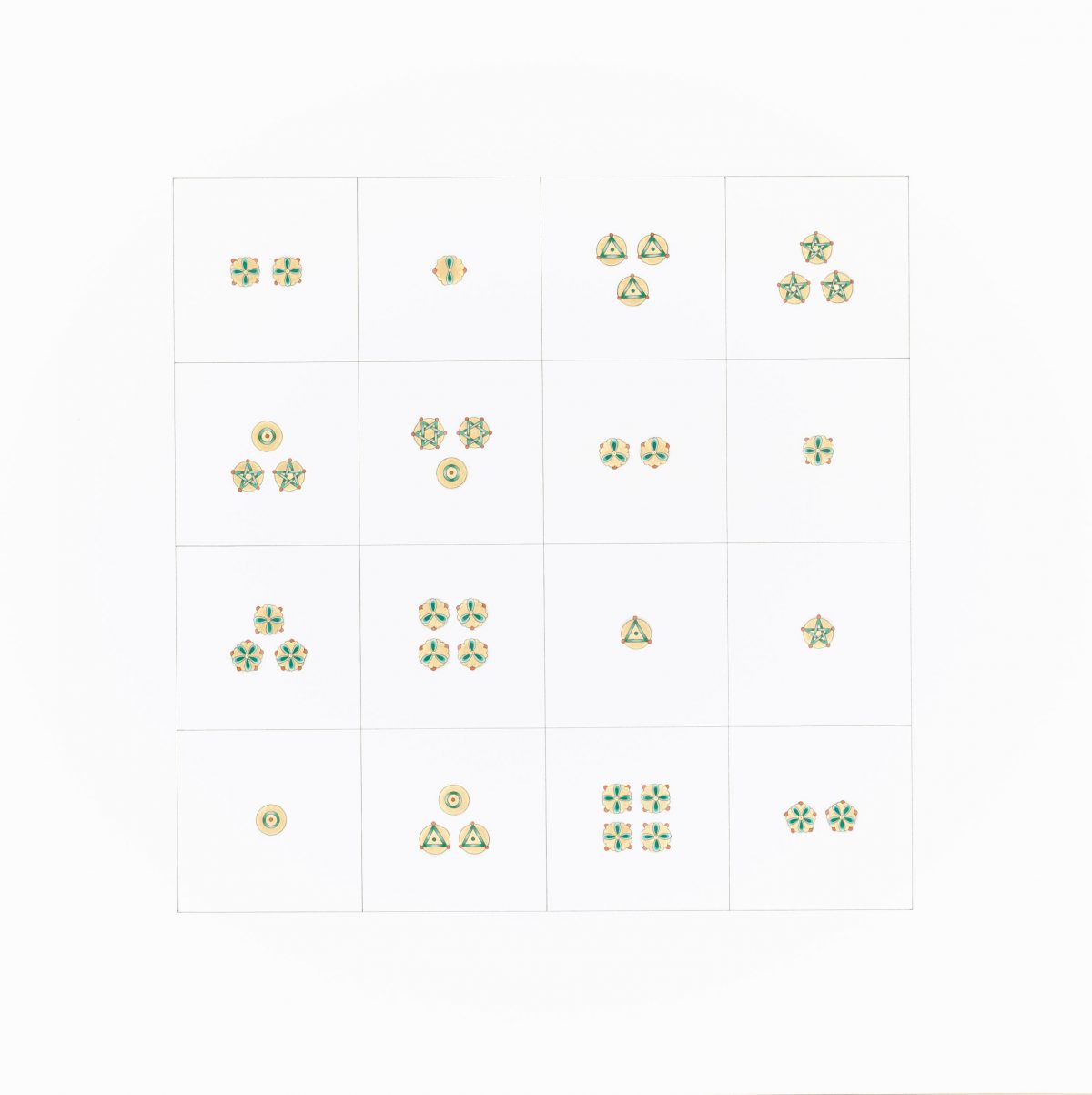

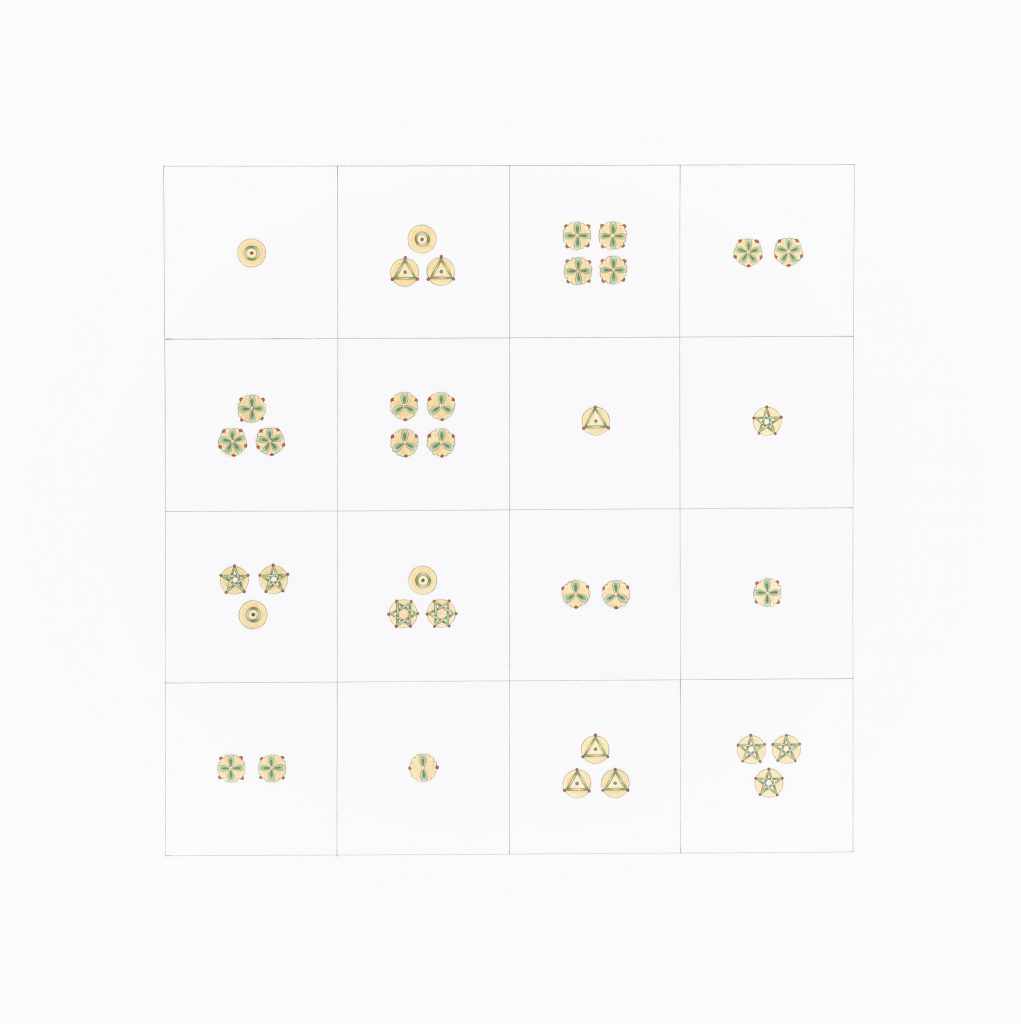

Design studies of It is He who Created You from a Single Soul

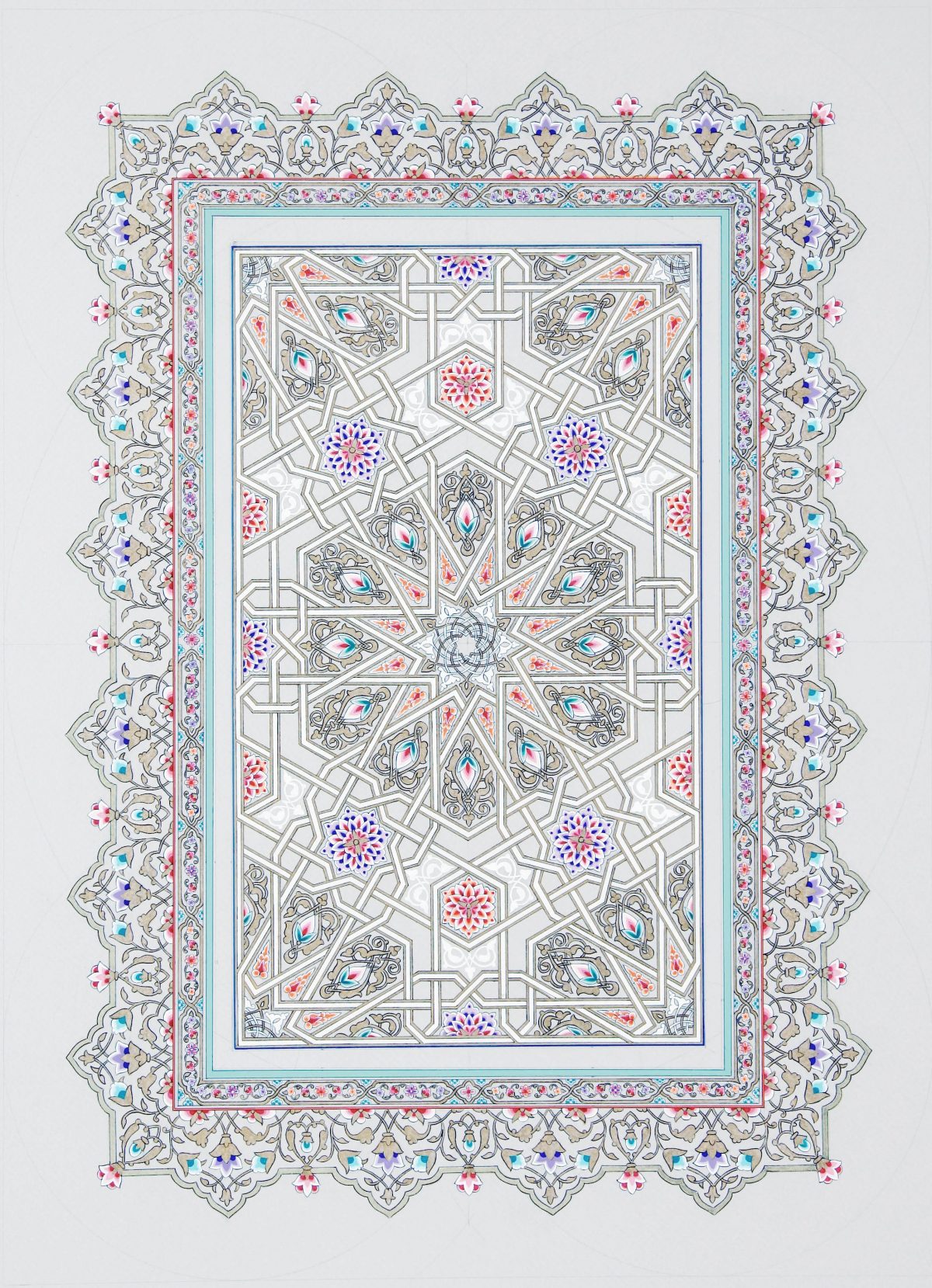

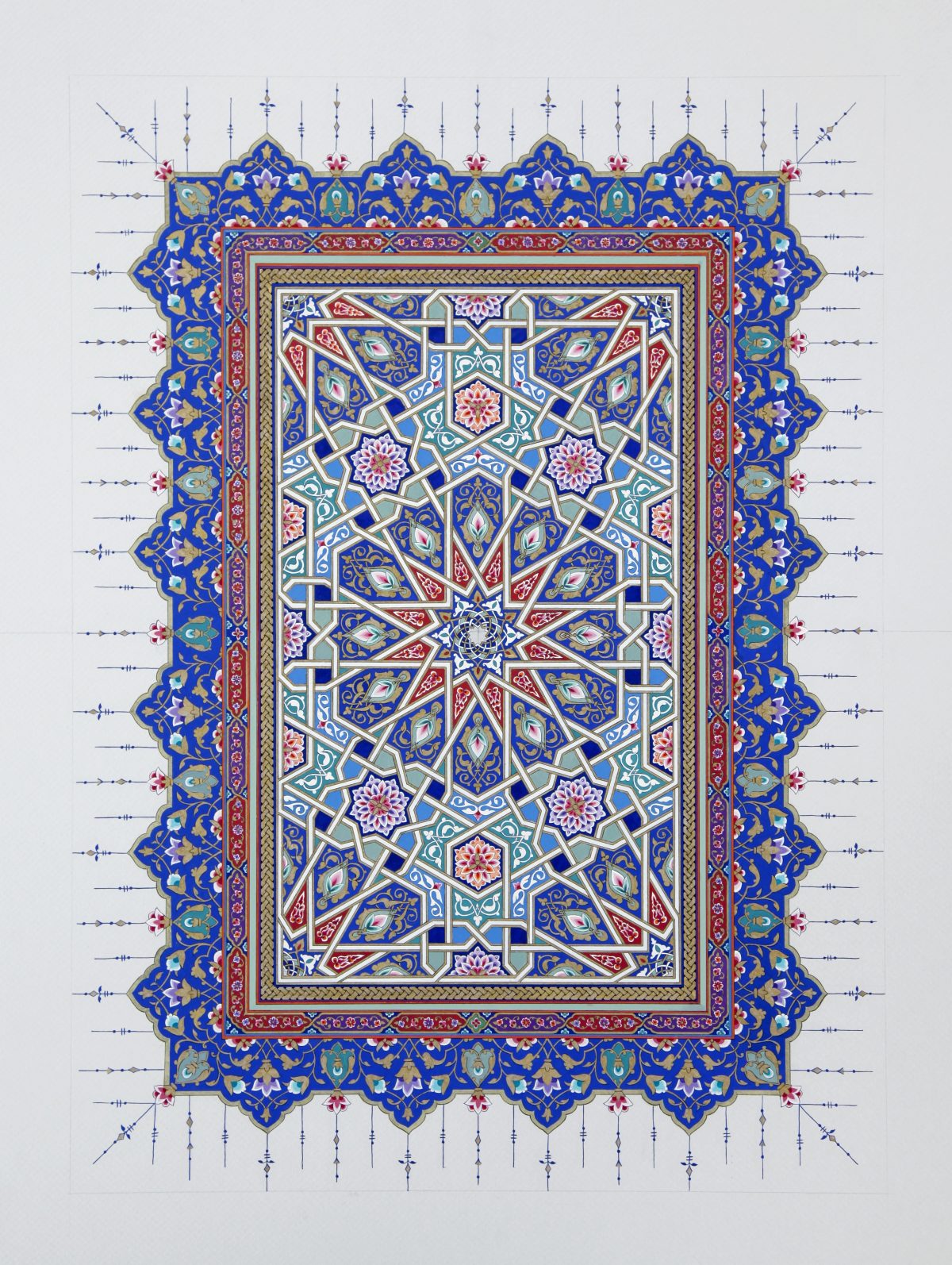

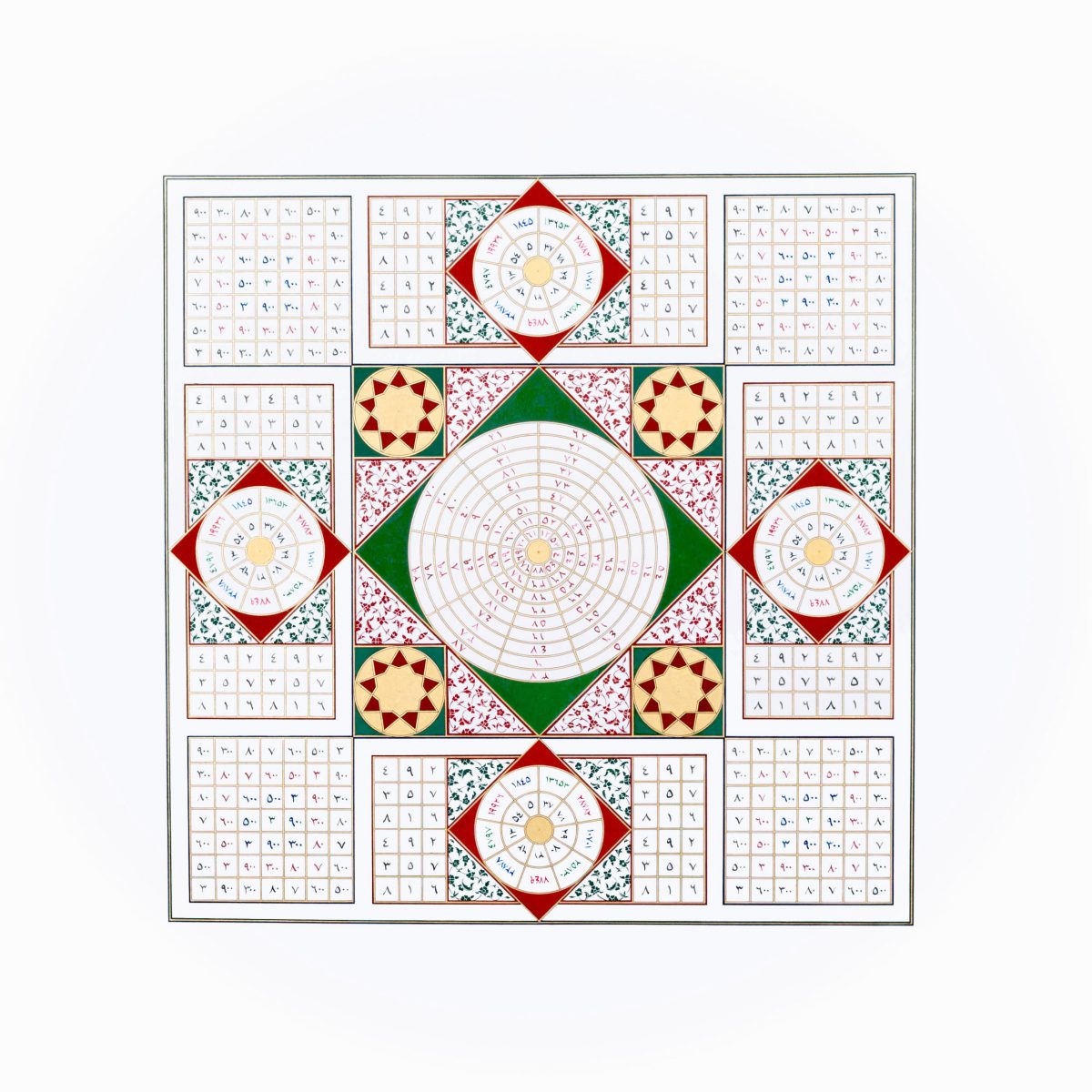

THE ISLAMIC CALIPHATES

2016

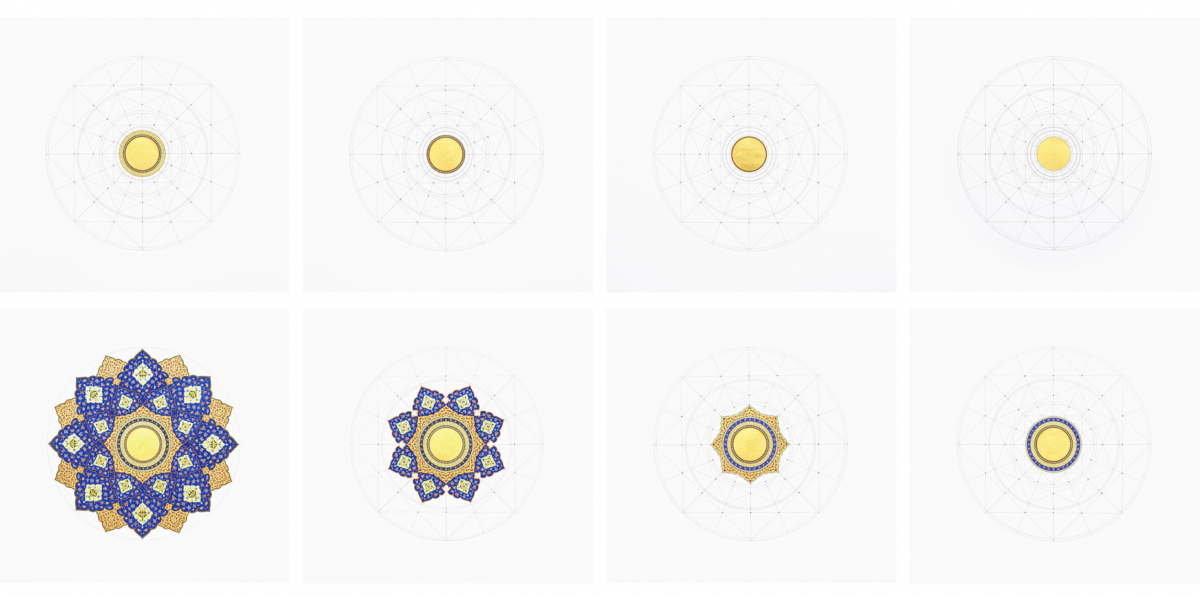

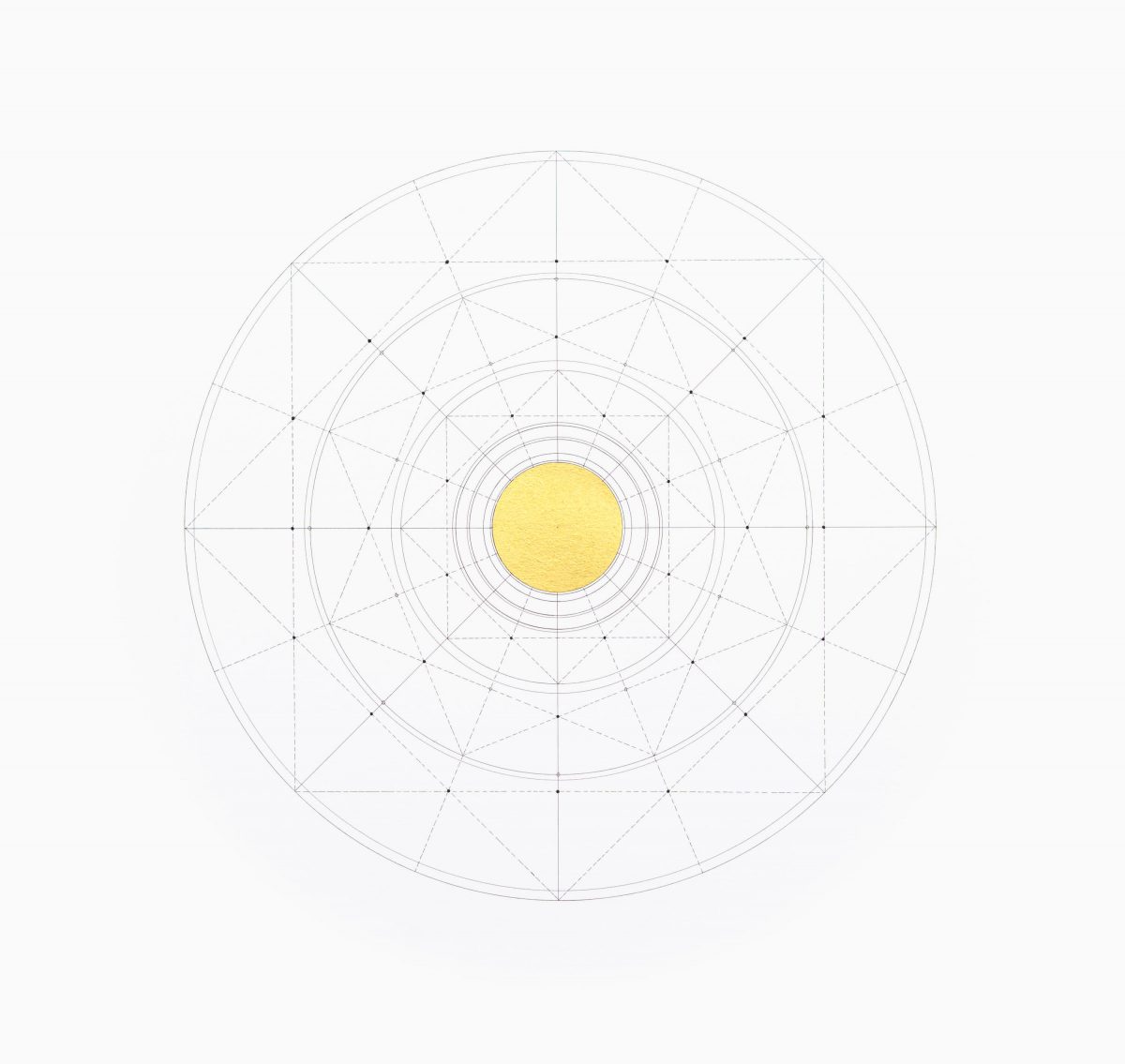

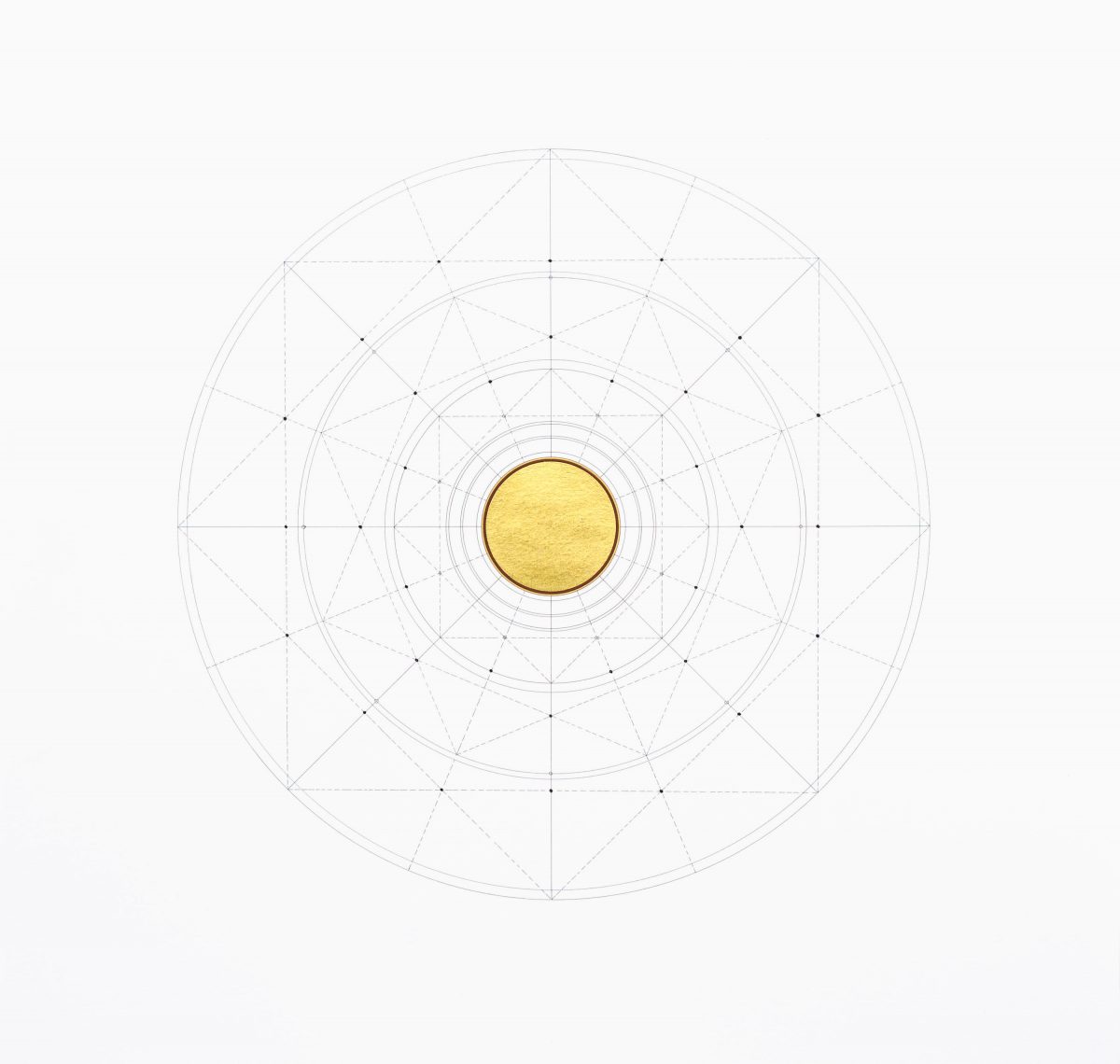

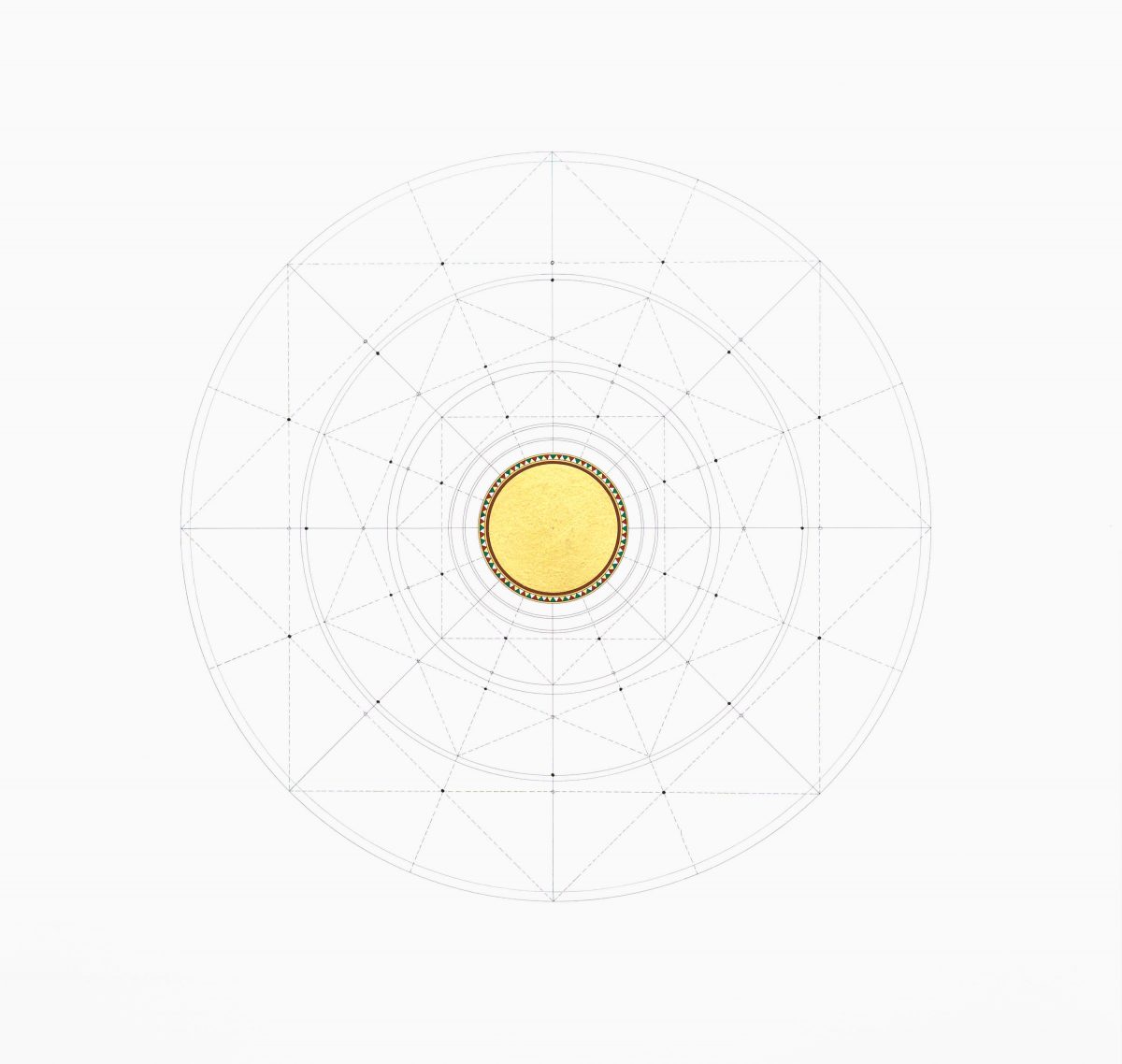

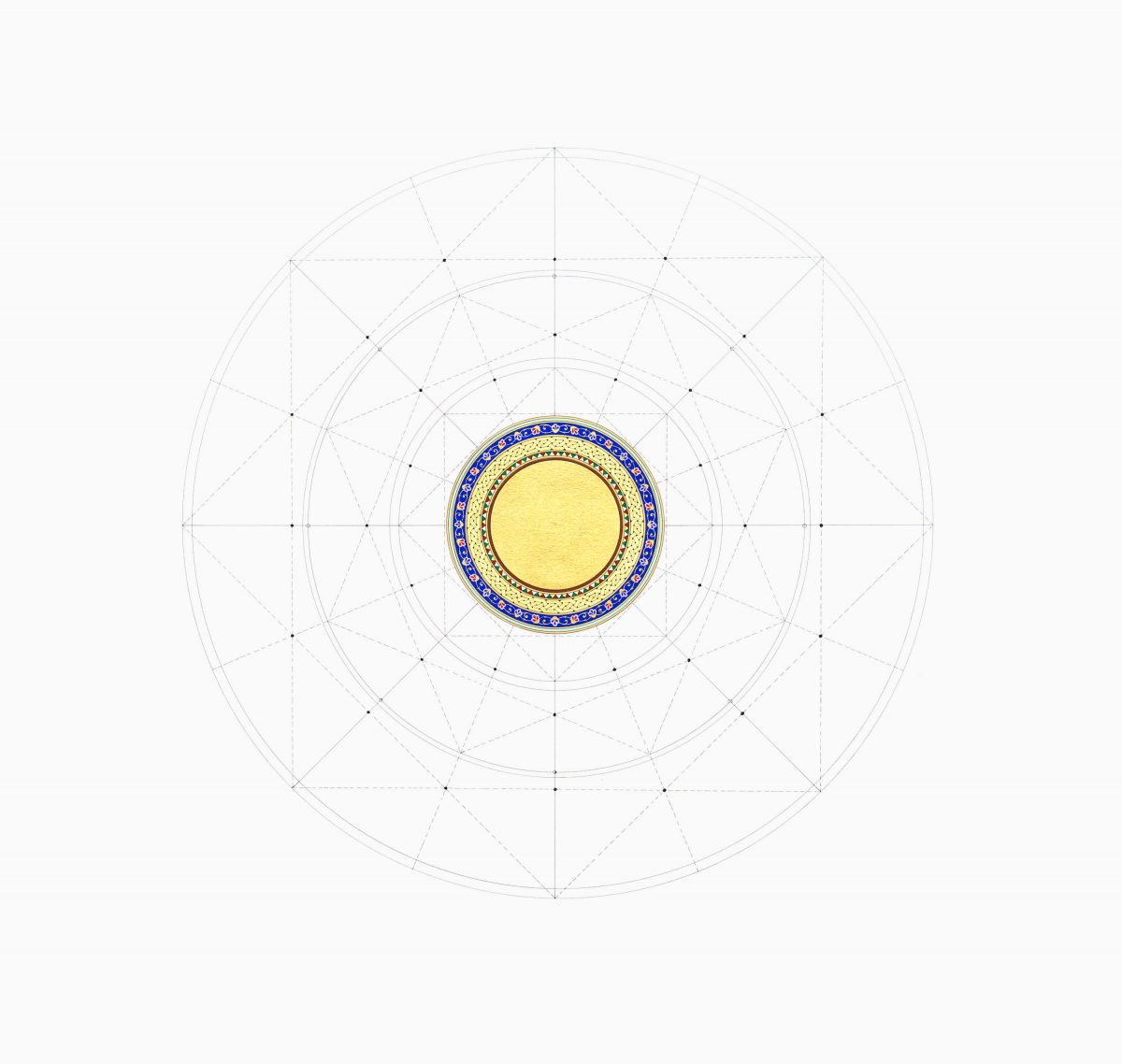

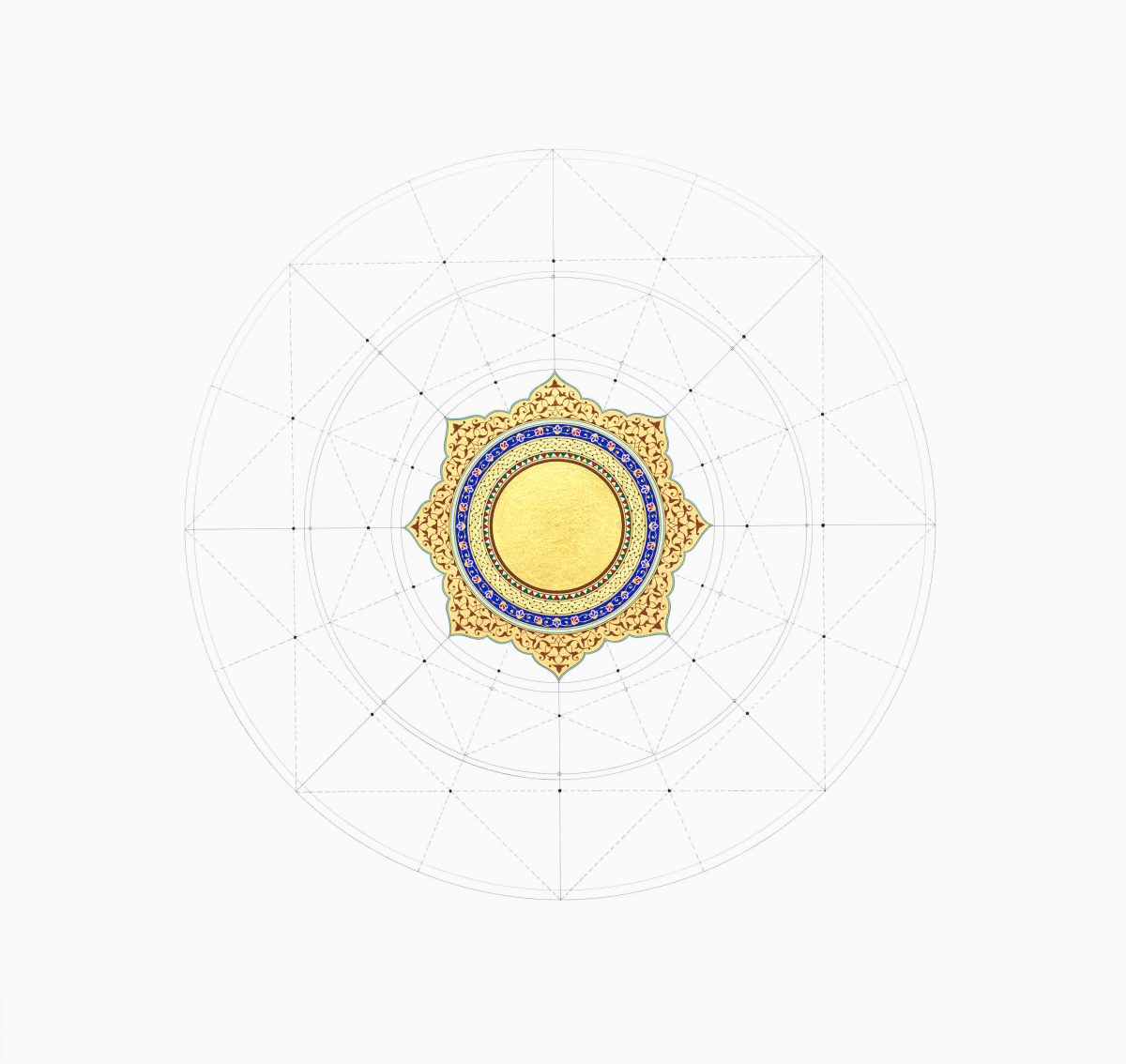

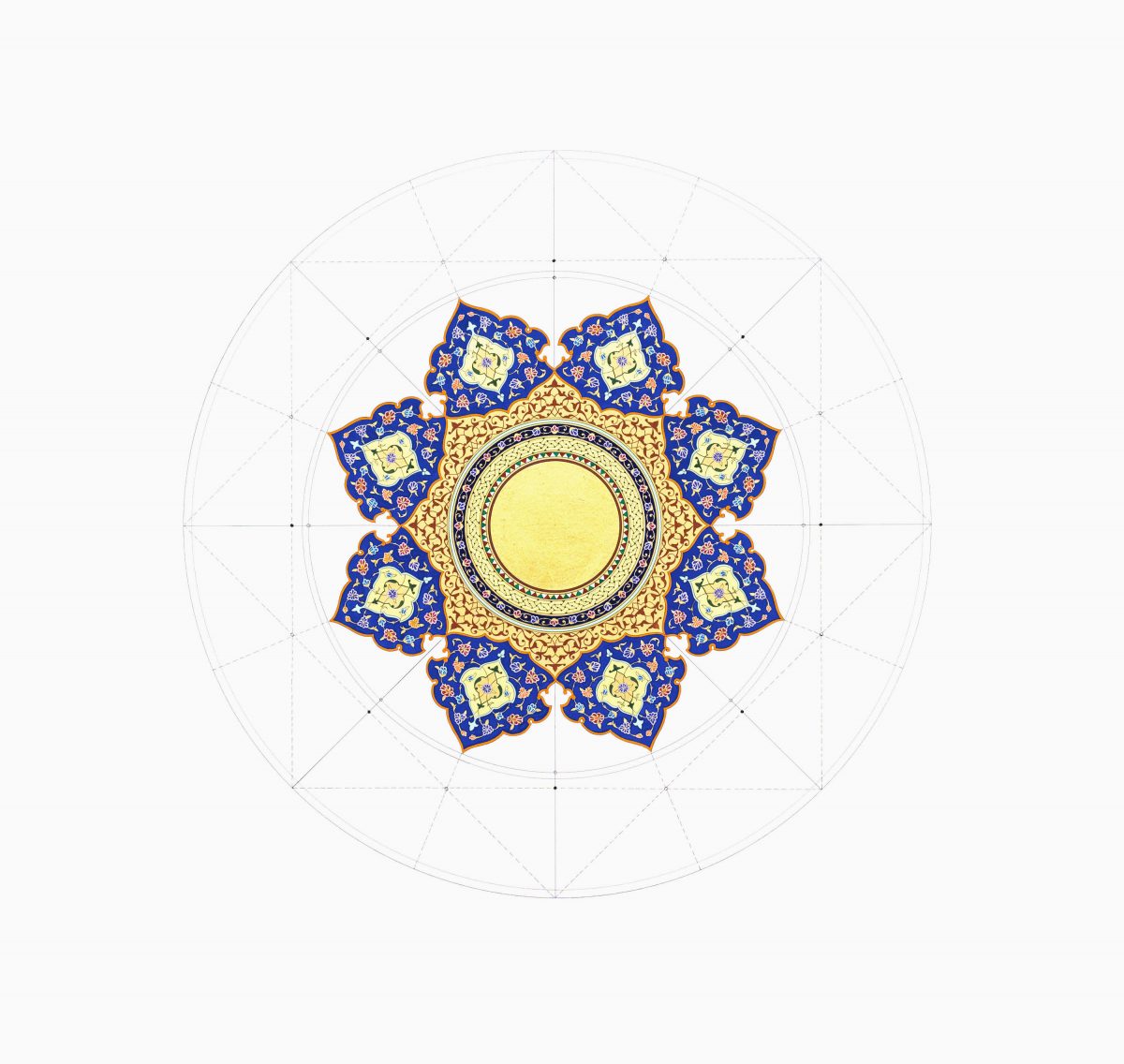

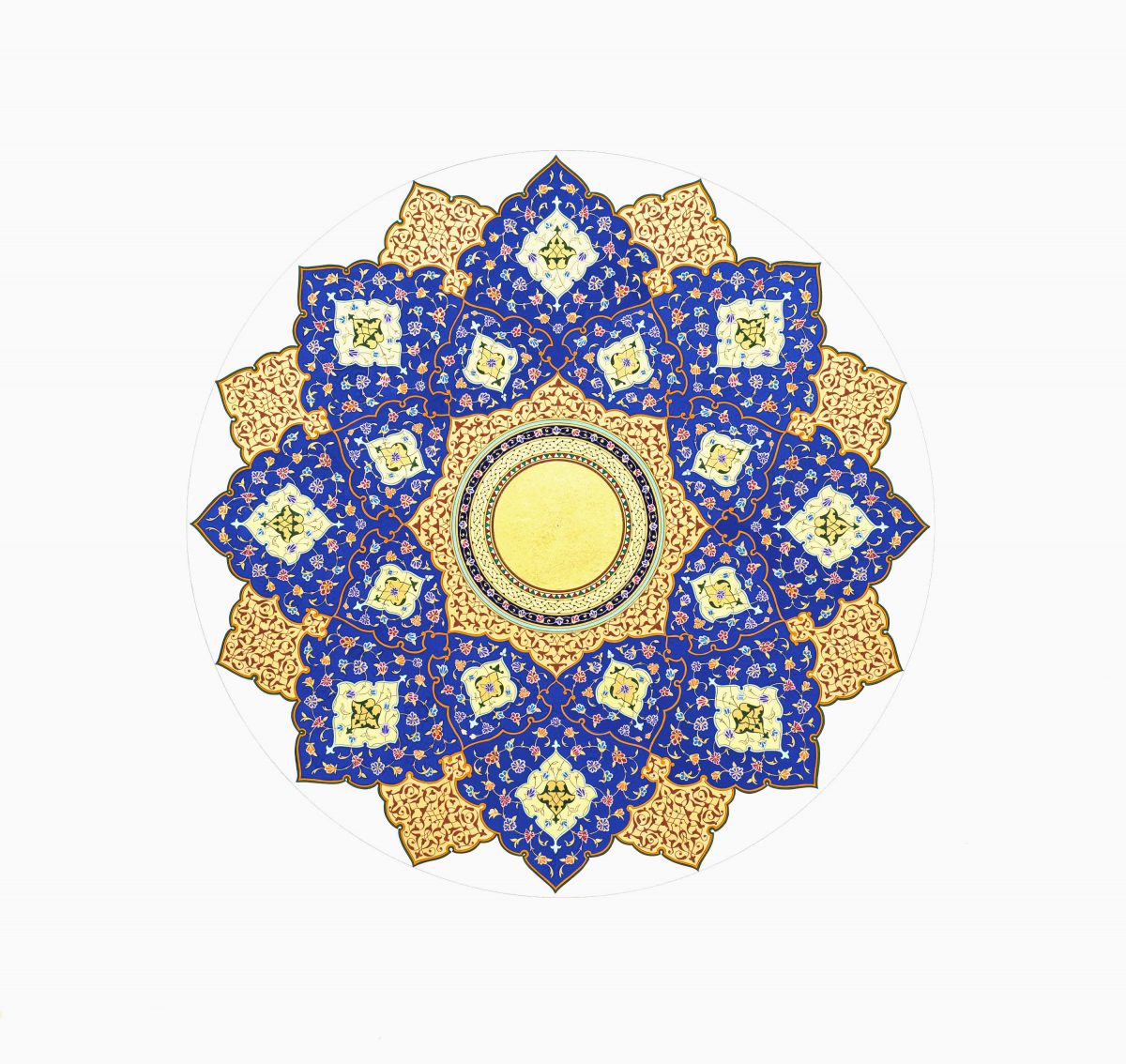

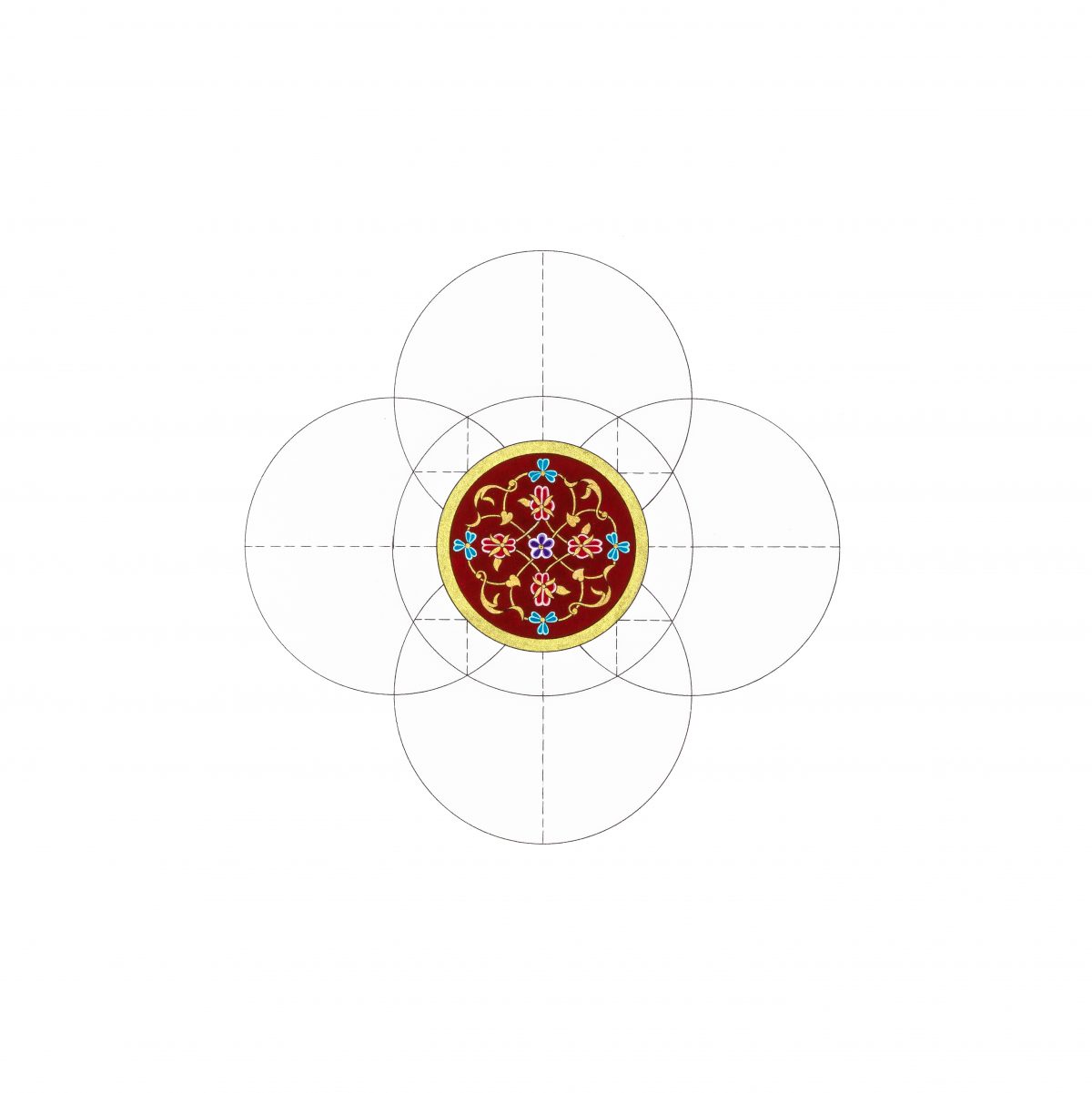

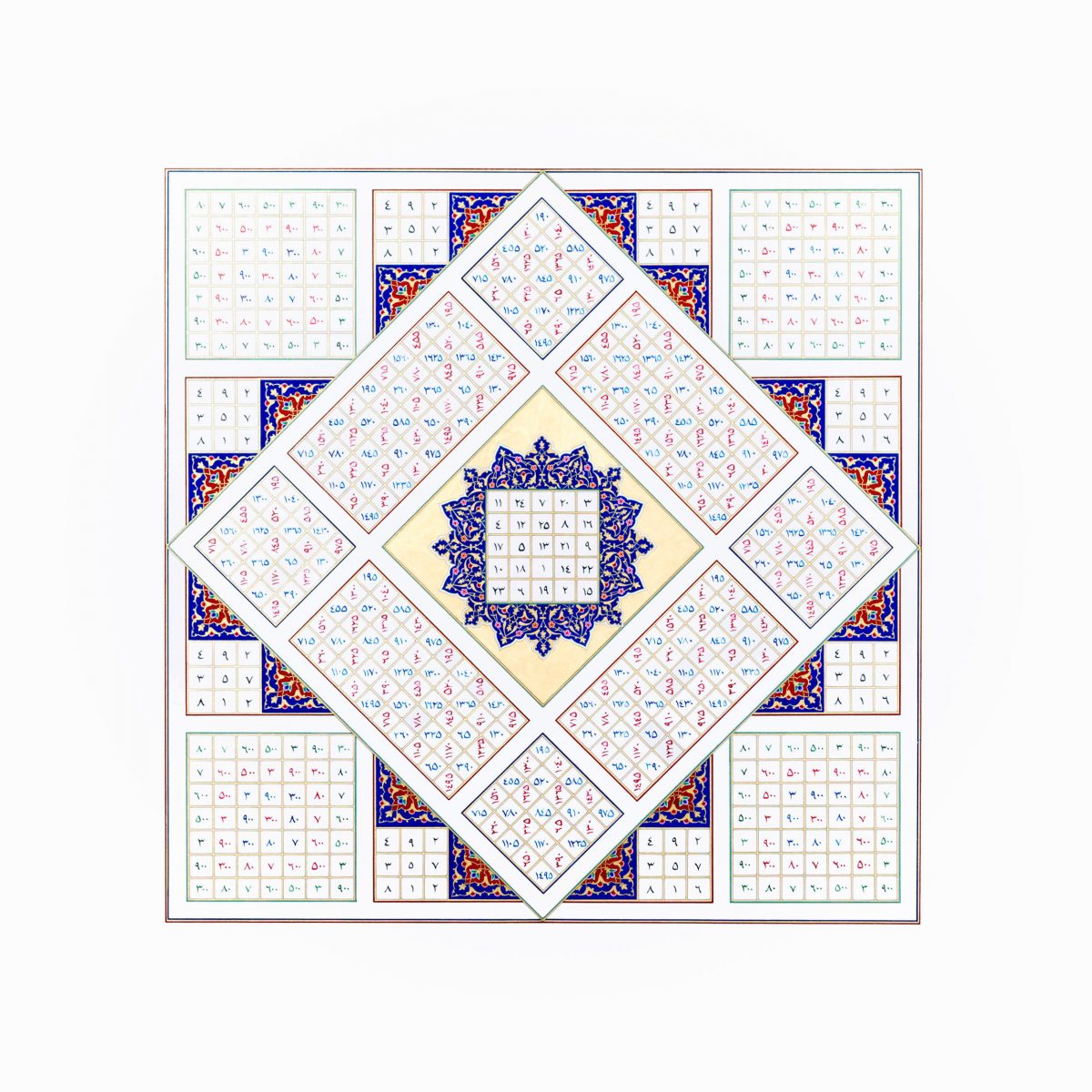

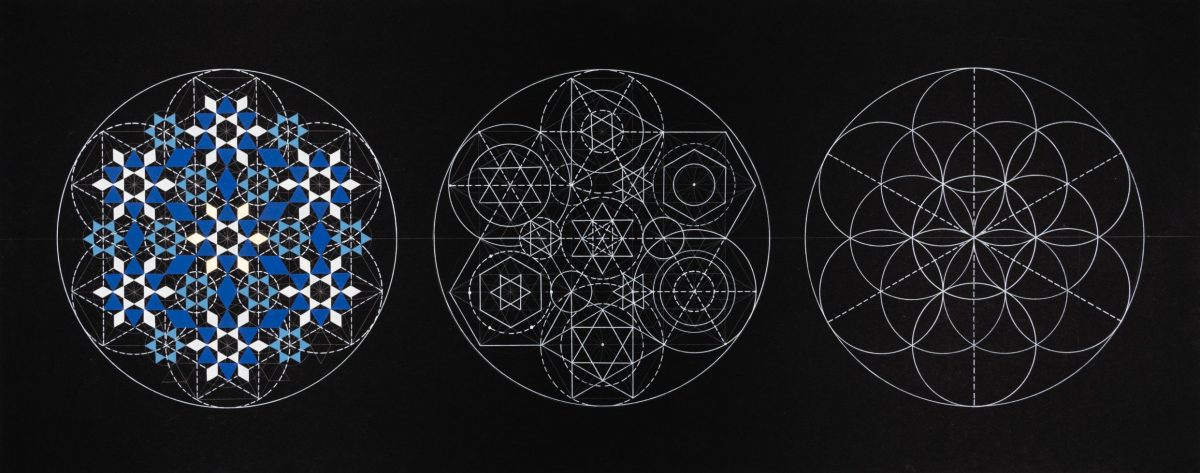

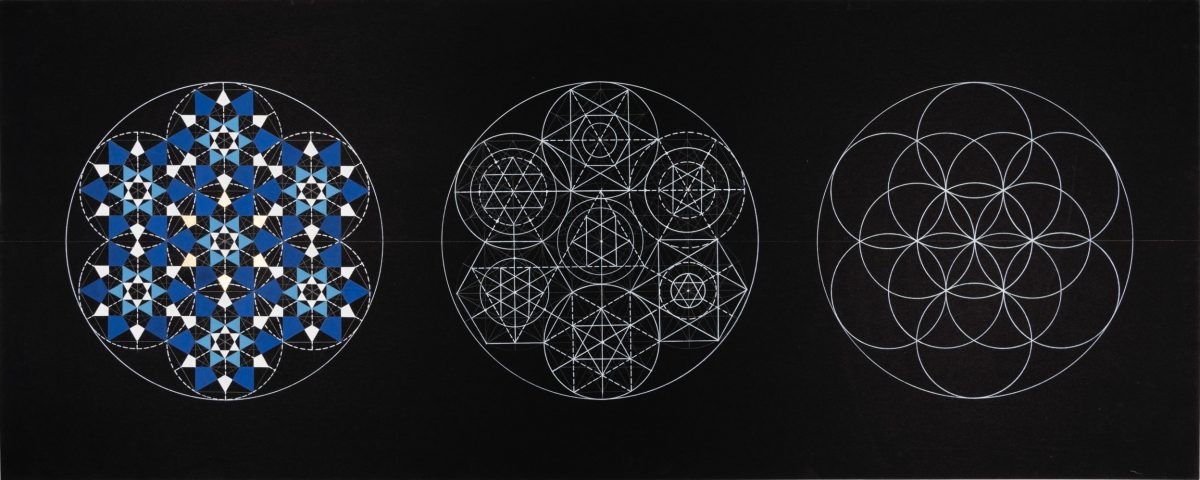

The work explores the history of the Islamic empires in relation to the development of the arts and crafts of the time, specifically focusing on the art of Quranic illumination. Stemming from the artists own training to obtain an ijaza (illumination master) this series combines Awartani’s interest in progressional, process revealing works with her traditional technique to express the development and evolution of Quranic manuscripts throughout history. The work unfolds over six panels and explores how each of the historical civilizations have contributed to this art form, building out from an illuminated core in layers. This piece also dually depicts the geographical expansion of the religion of Islam over time, starting from the gold circle which represents the birth of the religion in the Hejaz, all the way through to its peak which spans from the far East across to Europe which is portrayed in the final ‘shamsa’.

Each of the designs used throughout the different stages of the artwork, directly correlate with the style of illumination that was invented at the time. Portraying the evolution of this art form from being practically non-existent in the 7th century, mainly due to the fact that there was the fear of allowing anything to intrude upon the holy text of the Quran, and finally resulting in some of the highly decorative masterpieces you find in the later Islamic empires.

The presenting of these different styles beside one another is also a way to express the universality and highly diverse elements that not only make up the art of Illumination but furthermore is a reflection of the Islamic civilization as a whole, the idea of ‘Tawhid”, or unity within multiplicity which in essence is the core principal of Islam.

The Islamic Caliphates, 2016, Shell gold, gold leaf, ink and gouache on paper, 8 pieces – 60 x 60cm each. © Dana Awartani

ABJAD HAWAZ

2016

The Abjad Hawaz series is the result of Awartani’s developing of a visual system and code based on the scholarship and history of Ilm Al Huruf (the science of numbers). She builds upon the ancient numerical system, expansively divining an aesthetic language that revivifies the abjad and insists on its relevance. She is interested in the co-dependency inherent in geometry where the form is the result of a numerical expression – without which geometry would not exist. Awartani abstracts and imparts pure meaning using this method to create a harmonious and formal expression of complex notions that are difficult to succinctly synthesise.

Awartani’s visual language invites the viewer to participate in its coding and meaning-making, the direct translation of number into form becoming decipherable for viewers, even for those without a background in these traditions. In the system, each shape’s angles and repetitions equate to the numerical value or sum of the individual letter. So, as we engage with the form, the sense of the system emerges – we see that alef is not only shaped like the number one but is the number one. From here, a further kind of comprehension grows, with historic, scientific and mathematical symbolism potently coalescing as they are woven into the invested values of Awartani’s focussed expression. Understanding expands and we are able to appreciate alef as the original letter, the representative of the principle of unitary being. Accordingly, Awartani achieves a concurrent expression of this number, letter, and concept with a circle – the symbol of unity and creation. The other letters of the alphabet are said to have evolved from the letter alef into the variety and multiplicity of the alphabet, which for the hurufis, represents the cosmos. In the geometric tradition, the circle is the creator and originator of all geometry, where every design starts and finished within the circle.

Abjad Hawaz, 2016, Shell gold, gouache and ink on paper, 28 pieces – 24.5 x 24.5 each. © Dana Awartani

Alif from the Abjad Hawaz, Shell gold, gouache and ink on paper, 24.5 x 24.5. © Dana Awartani

Dal from the Abjad Hawaz, Shell gold, gouache and ink on paper, 24.5 x 24.5. © Dana Awartani

Noon from the Abjad Hawaz, Shell gold, gouache and ink on paper, 24.5 x 24.5. © Dana Awartani

Meem from the Abjad Hawaz, Shell gold, gouache and ink on paper, 24.5 x 24.5. © Dana Awartani

Dha from the Abjad Hawaz, Shell gold, gouache and ink on paper, 24.5 x 24.5. © Dana Awartani

Dhad from the Abjad Hawaz, Shell gold, gouache and ink on paper, 24.5 x 24.5. © Dana Awartani

Ghayn from the Abjad Hawaz, Shell gold, gouache and ink on paper, 24.5 x 24.5. © Dana Awartani

Kaf from the Abjad Hawaz II series, 2017, shell gold, gouache and ink on paper, 26 x 66 cm each. © Dana Awartani

Sheen from the Abjad Hawaz II series, 2017, shell gold, gouache and ink on paper, 26 x 66 cm each. © Dana Awartani

Kha from the Abjad Hawaz II series, 2017, shell gold, gouache and ink on paper, 26 x 66 cm each. © Dana Awartani

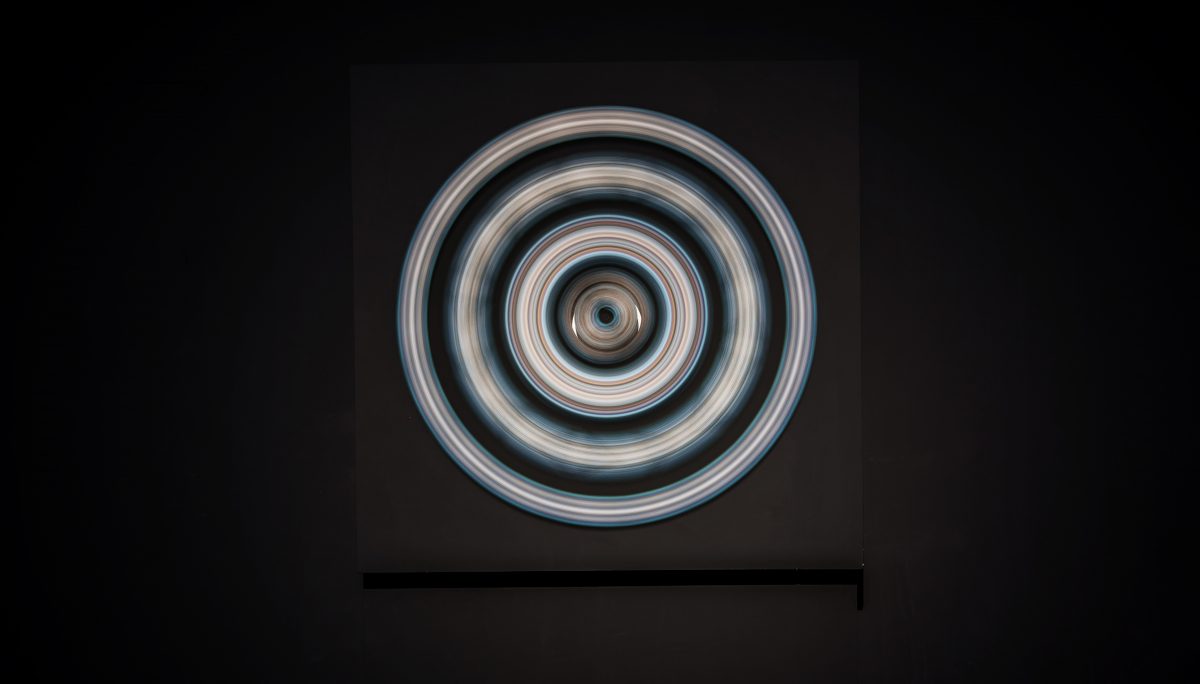

ALL HEAVENLY BODIES SWIM ALONG, EACH IN ITS ORBIT

2016

All Heavenly Bodies is a dynamic visual expression of intricate meaning-making inspired by ideas that emanate from the Quran’s linguistic patterns. This kinetic sculpture aims to reveal the structural complexity that invests power and significance in one of the only two palindromes found in the entirety of the Quran; which are a form of wordplay dating back to 79AD, where by letters or numbers are read identically forwards and backwards.

In Surah Yasin in the Quran, we read ‘all [heavenly bodies] swimming along, each in an orbit’ (‘kul fylfalak yasbahoon’) expressed in a palindromic pattern that both mimics and clarifies meaning. Focussing on the consonants, we see the pattern emerge as we read of the heavenly bodies in their orbit (‘kul fyfalak’):

ك ل ف ي ف ل ك

In this coded linguistic form, the letters kaaf, laam and fa (ك ل ف) seem to encircle the pivoting letter ya (ي). It is as if each letter, signifying the heavenly bodies, has been set in their own orbiting sphere. Further, the ya (ي) at the heart of these concentric circles invokes the next word, yasbahoon – ‘floating’ or ‘swimming’ – the verb which propels the letters on their course.

This analysis is pushed further through Awartani’s research and experimentation with code, applying her visual Abjad Hawaz system to extrapolate the complexity of the symbiotic meaning and form. This system is a means to alternatively articulate letters and numbers, purely abstracting the meanings they impart through geometry. She uses the method to create a harmonious and formal expression of a notion too complex to synthesise succinctly.

Appearing to expand from the center, their orbit is reminiscent of the planetary motion the palindrome itself implies. The whole meditative motion encourages the viewer to engage with meaning-making on a different intellectual plane. To heighten this state of focus, the piece is accompanied by the music of the Sufis, evocative of the whirling dervish ceremonies devised to invoke the same heightened intuitive engagement.

Installation shot of All (heavenly bodies) swim along, each in its orbit, at the Yinchuan Biennale, 2016. Egg tempera on wood and mechanical structure, 100 X 100 cm. © Dana Awartani

All (heavenly bodies) swim along, each in its orbit, 2016, Shell gold, gouache and ink on paper, 100 x 100 cm. © Dana Awartani

AND YOUR LORD YOU SHOULD GLORIFY

2016

The piece is a continuation of Awartani’s study exploring the subject of palindromes within the Quran, which are a form of wordplay where by words, phrases, numbers or any other sequence of characters that when read backwards or forwards are the same.

In this piece she has focused on a verse from Surah Al- Muddaththir (The Cloaked One), which reads as ‘rabbaka fakabbir’ (And Your Lord You Should Glorify, Quran 74:3). Here, reading the sentence backwards including vowels would not create a palindrome. However, taking out consonants only (which are here: r, b, k, f, k, b, r) can create a palindrome.

Continuing with here research and experimentation with developing codes, Awartani has taken the practice of palindromes a step further by converting each letter of the sentence into there numerical value using the Abjad Hawaz system and then into a symbol that embodies that number, in turn allowing the viewer to decipher this code.

And Your Lord You Should Glorify, 2016, Shell gold, ink and gouache on paper, 50 x 190 cm. © Dana Awartani

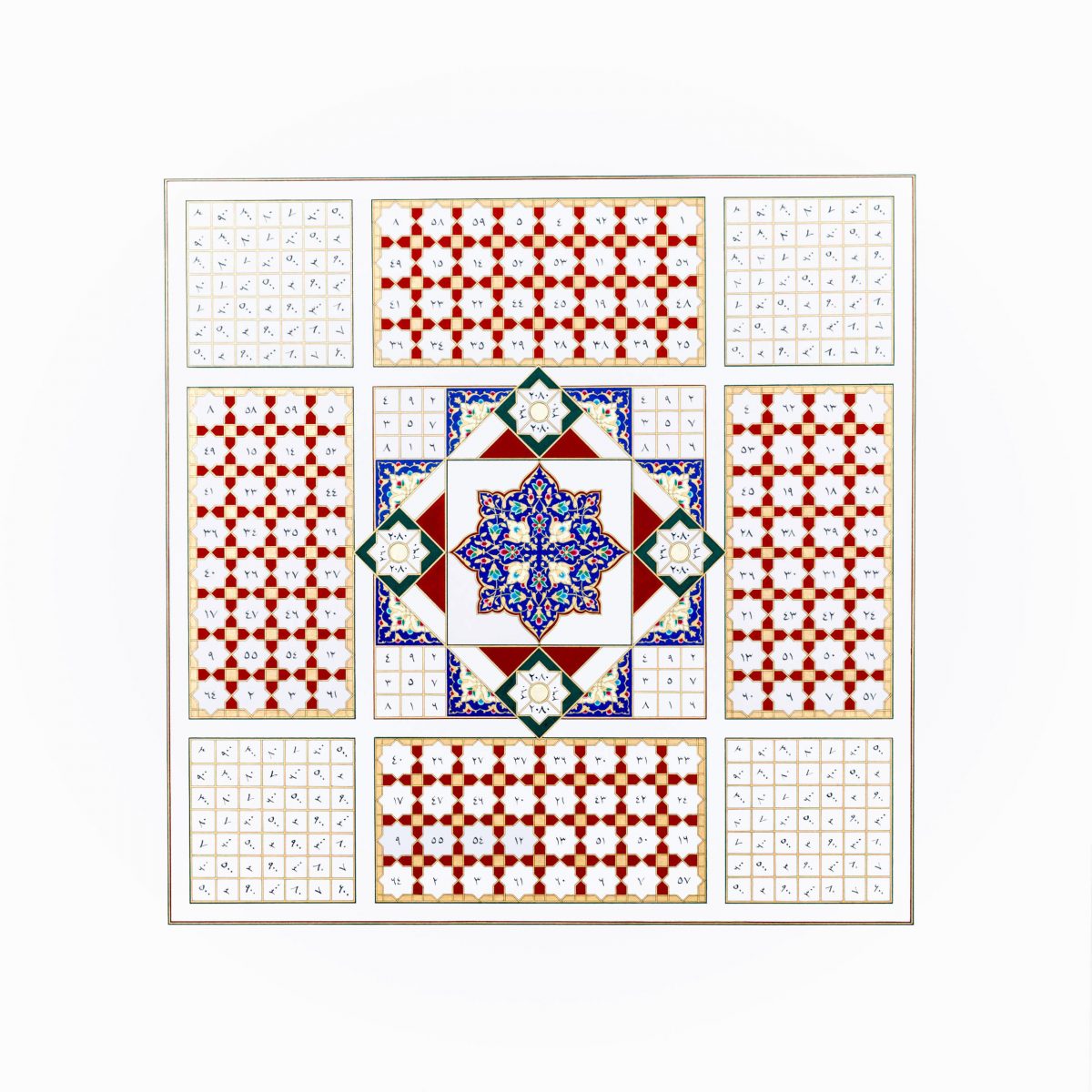

FIVE STAGES OF GRIEF

2015

In the Five Stages of Grief series, Awartani uses the threads of talismanic references drawn from the Ottoman Empire and rooted in Islam to make connections to lost elements of Saudi heritage. The artist first encountered talismanic shirts in the Topkapi Palace Museum in Istanbul – pieces which were once said to protect the Sultans as they wore these kaftans before going to war and there wives during childbirth. The artist has taken original textiles from the Thageef tribe in Saudi, coded patterns which once denoted where a tribe came from. During the founding years of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, all such colourful and distinctive costumes were banished, with the neutral and harmonised black abaya and white kaftan encouraged for men and women, as a way of unifying the tribes.

Stitched to the original garments are Awartani’s signature magic squares, where she has taken the five stages of grief and applied one stage to each garment. The artist has referenced to the ancient system used in divination where by the letters of the ‘abjad’ are divided into four parts and the seven letters in each part are assigned to one of the elements – air, fire, water and earth. Here she has created her own coded interpretation by attributing one of the elements to a specific stage of grief, with the last being a combination of all the elements, as these garments are intended to be seen as an aid to overcome the various emotions in the process of grieving. In this work, each symbol or letter of the language she has built is stitched into the cloth, the knots and ties intended as a reference to the sorrow implicit when layers of history are wiped out in the name of modernization. At the same time, the juxtaposition of old and new binds Awartani’s own complex reading of the world around her onto the ancient artifacts.

Installation shot of The Five Stages of Grief at the Museum of Contemporary Art Detroit, 2015, antique textile and embroidery on cotton, 85 x 144 cm each. © Dana Awartani

Anger from the Five Stages of Grief, 2015, Antique textile and embroidery on cotton, 85 x 144 cm. © Dana Awartani

Bargaining from the Five Stages of Grief, 2015, Antique textile and embroidery on cotton, 85 x 144 cm. © Dana Awartani

Depression from the Five Stages of Grief, 2015, Antique textile and embroidery on cotton, 85 x 144 cm. © Dana Awartani

Denial from the Five Stages of Grief, 2015, Antique textile and embroidery on cotton, 85 x 144 cm. © Dana Awartani

Acceptance from the Five Stages of Grief, 2015, Antique textile and embroidery on cotton, 85 x 144 cm. © Dana Awartani

Contributing Text by the Mansoojat Foundation

The costumes of the tribes of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia are as diverse in cut, style, and embroidery as the regions these tribes inhabit; accordingly each costume is a reflection of the different geographic and climate environment the tribe lives in. However distinct these costumes are, they all share one common feature in that they are an expression of the creativity of the women who designed and created them; the costumes are an amalgam of practicality, elaborate beading, and intricate embroidery. The harsher the environment and the warmer the climate is, as in the case of the desert of the Empty Quarter where the Bani Murrah, a branch of the Bani Yam tribe dwell, the more somber the costume. The dresses of these costumes generally have a wider cut with ample sleeves to accommodate the heat, with hardly any embroidery on them. The more fertile and arable the land, the more vibrant the fabrics used, and the more colourful the embroidery echoing the beautiful local vegetation as in the bright and cheerful costumes of the Southern Region of Asir, and the costumes of the Bani Saad and Bani Malik tribes in the mountainous region of the Hijaz.

Aside from a few environmental idiosyncrasies, the tribal women of Arabia, like women the world over, enjoy wearing their make-up, adorning themselves with jewelry, and perfuming themselves with local herbs and flowers. They are pragmatic and practical and believe in carefully managing their precious resources; when the fabric of their costumes becomes threadbare and worn out, they simply cut out the embroidered segments and attach them back on a newly sewn base dress, time and time again.

The Thaqeef tribe is one of the oldest and noblest tribes of Arabia established fourteen centuries ago, before the advent of Islam, in and around the town of Taif in the mountain range of the Hijaz. Taif was famous for its agriculture, its pastureland and shepherding, and its markets. It was in Taif where the wealthier merchant families of the neighboring holy city of Makkah spent their summers because of its cooler climate. It was the first town, outside of Makkah, the prophet Mohamed (pbuh) took his message of Islam to. In his first attempt, he met with the formidable tribe of Thaqeef who refused to accept his message and fought him in the battle of OKAZ. Eventually, Thaqeef accepted Islam and played an important role in the spreading of its message. The people of Taif and its surroundings farmed its fertile land, growing amongst the variety of fruits and vegetables, pomegranates and grapes that they used to dye their textiles. The Thaqeef tribes have two known styles of costumes, the Nimri thobe of the Hada area and the Mubaqar thobe of the Shafa area. The costumes are similar using alternating bands. The difference between the two styles is in the embroidery, the use of tie-dye, and the use of beading. In the Nimri thobe, the yoke and arm bands are embroidered with gold thread, the small white decorative motif above the hem is tie dyed, and often the dress has an accompanying belt made of metal beads and shells. Whereas the Mubaqar thobe is sewn together in alternating bands, the yoke and sleeve cuffs are embroidered with white and red cotton thread and the hem decoration is applique.

Several tribes of the Hejaz region such as the Thaqeef, Bani Malik and Bani Saad live in the valley of Wadi Mahram close to Taif. Despite living in such close proximity to each other, separated only by a few kilometers, and despite the similarities of their costumes, their clothes are easily and distinctly distinguished from each other by the details in their embroidery and beading. The rich costumes of these particular tribes are only a small illustration of the rich textile and costume heritage of the people of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia.

HEAVENLY BODIES

2015

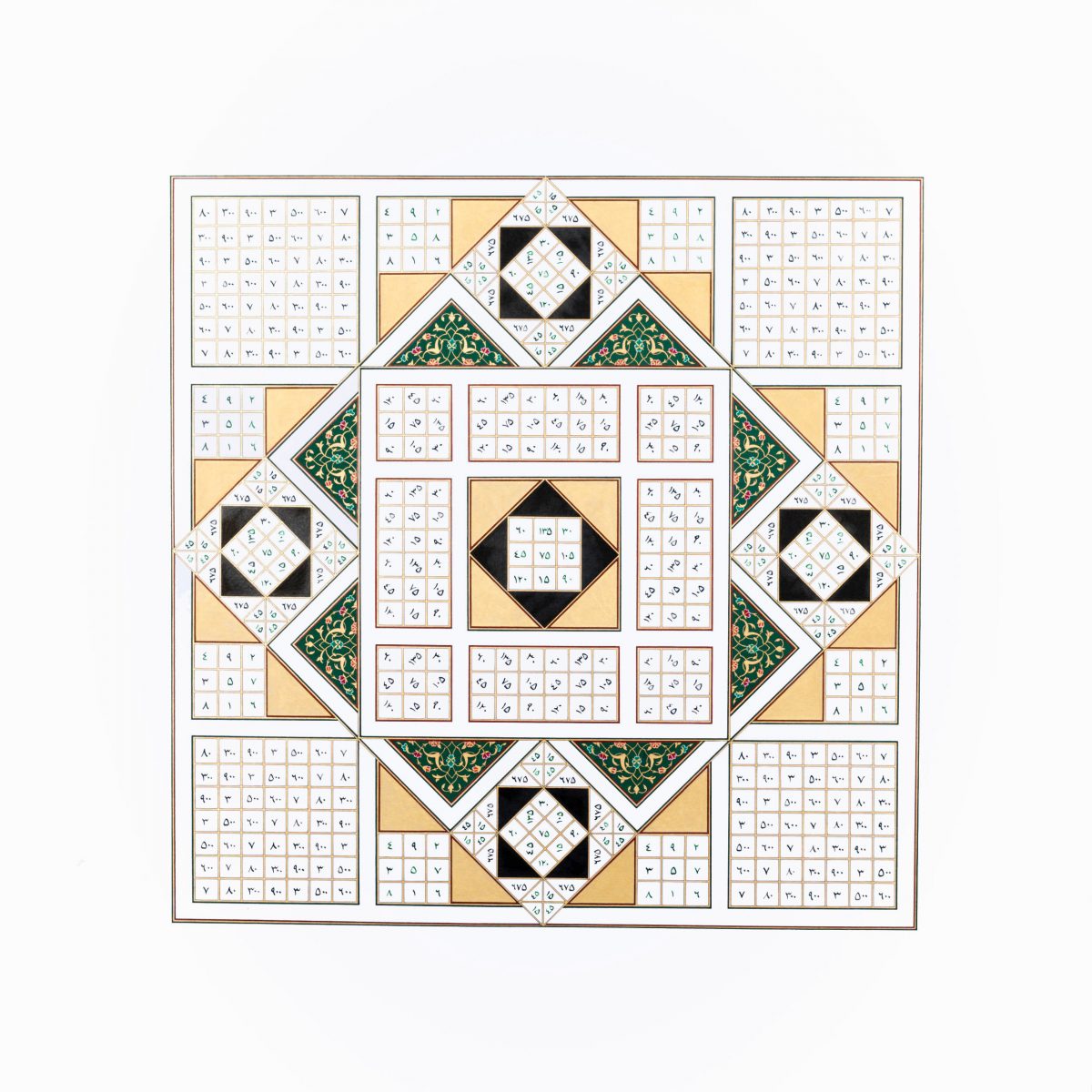

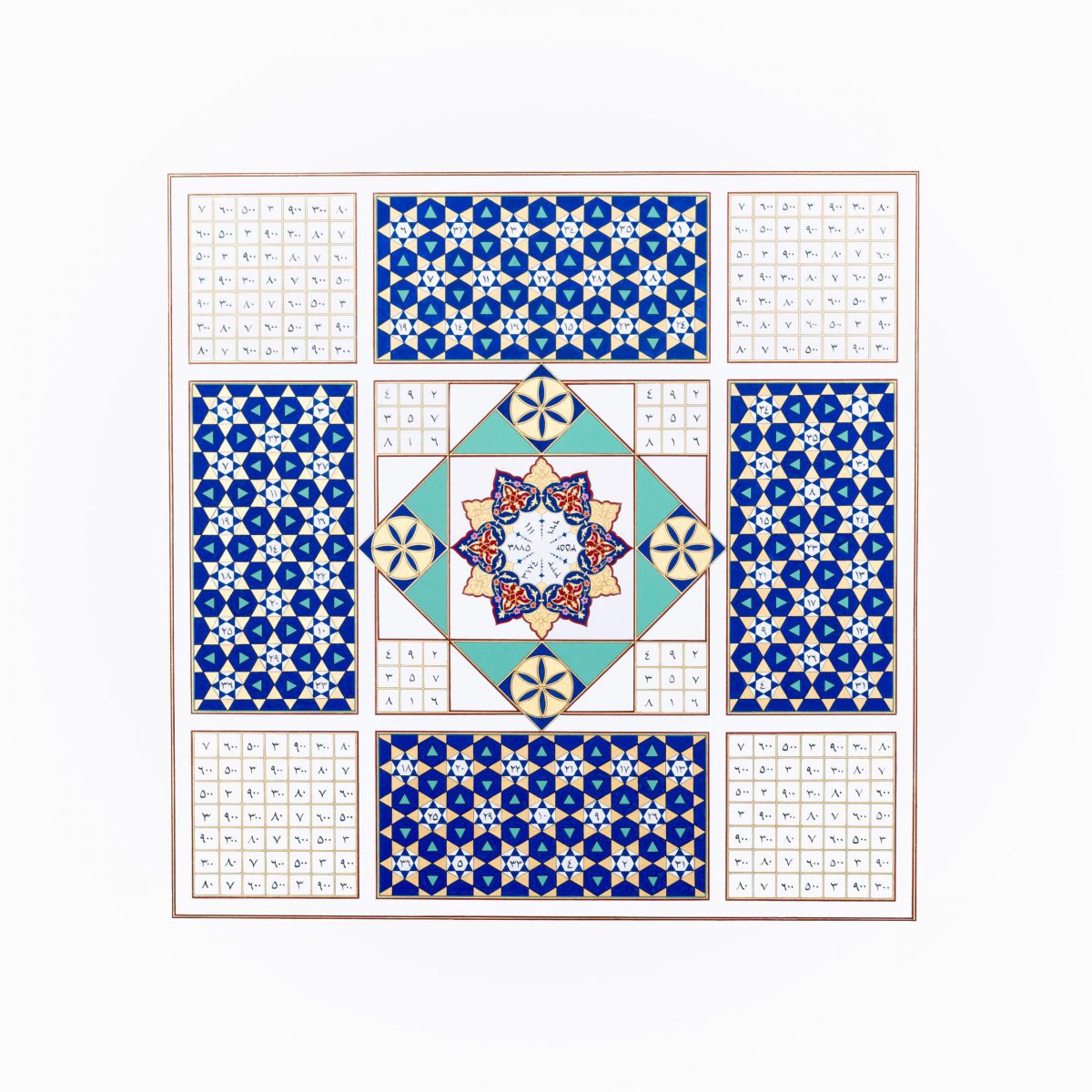

The Heavenly Bodies series combine Awartani’s research into both talismans and enchanted squares, in particular an investigation into how they were created, used and their spiritual significance. Each of the central squares (from 3 to 9 squared) are affiliated with one of the seven classical planets, a day in the week and an angel – they were also once regarded as a form of protection as well as a source of higher spiritual knowledge through numerology. These works, created using traditional methods and pigments, are structured based on the first square, which sits at the top right of the work and holds the code to deciphering which planet has been illustrated. Where once these coded paintings might have been used as designs for weavings on clothes, here they work as illuminations, with each of the seven works exploring form, pattern, numerology and mysticism, functioning almost as a manifestation of the artist’s explorations into the threads of divination in ancient Islam. By bringing these early practices into a contemporary and increasingly globalized context triggers the question surrounding the possible reversion to more instinctive rituals.

Saturn from the Heavenly Bodies series, 2015, shell gold, natural pigments and ink on paper, 59 x 59 cm. © Dana Awartani

Jupiter from the Heavenly Bodies series, 2015, shell gold, natural pigments and ink on paper, 59 x 59 cm. © Dana Awartani

Mars from the Heavenly Bodies series, 2015, shell gold, natural pigments and ink on paper, 59 x 59 cm. © Dana Awartani

Sun from the Heavenly Bodies series, 2015, shell gold, natural pigments and ink on paper, 59 x 59 cm. © Dana Awartani

Venus from the Heavenly Bodies series, 2015, shell gold, natural pigments and ink on paper, 59 x 59 cm. © Dana Awartani

Mercury from the Heavenly Bodies series, 2015, shell gold, natural pigments and ink on paper, 59 x 59 cm. © Dana Awartani

Moon from the Heavenly Bodies series, 2015, shell gold, natural pigments and ink on paper, 59 x 59 cm. © Dana Awartani

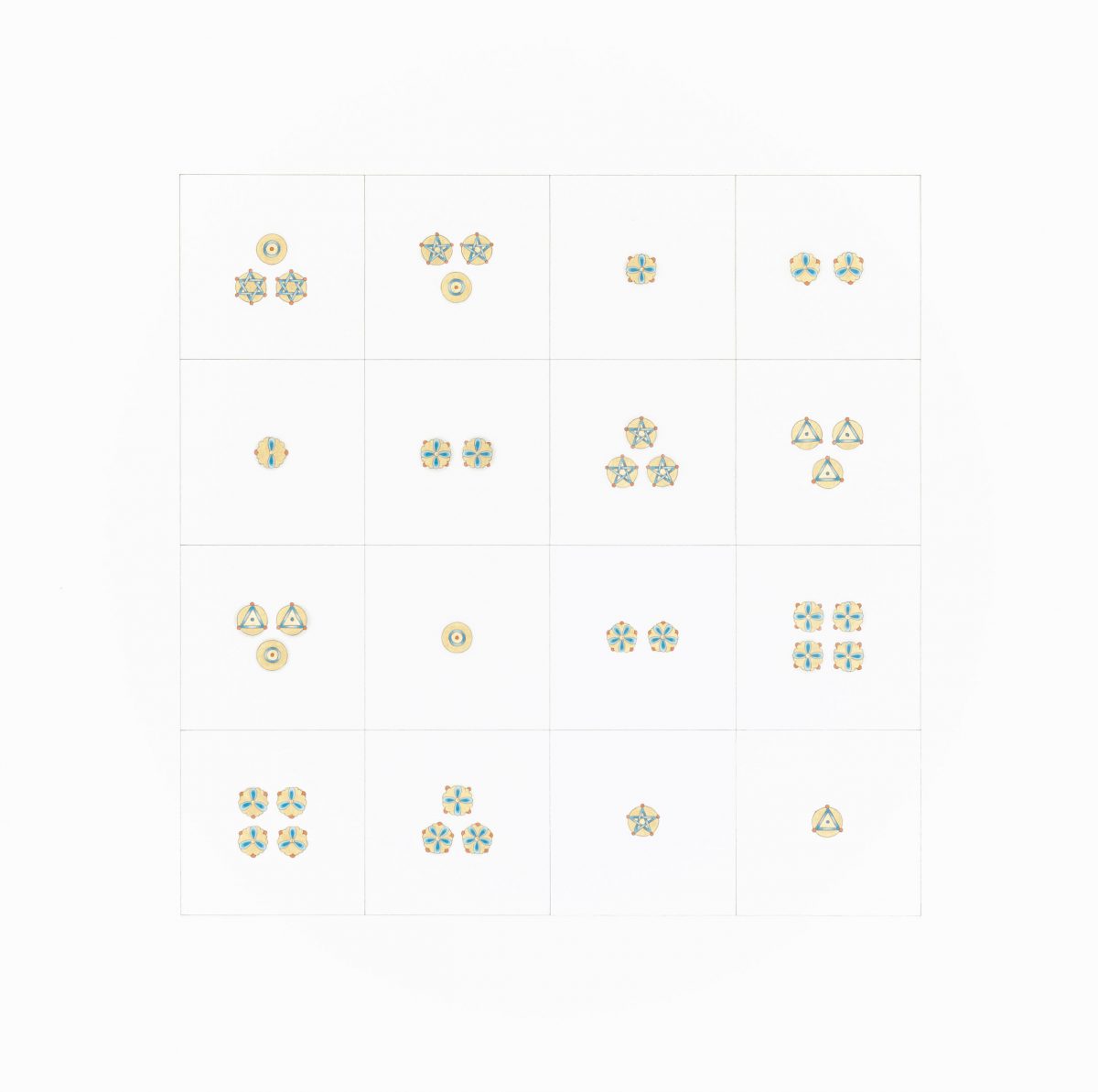

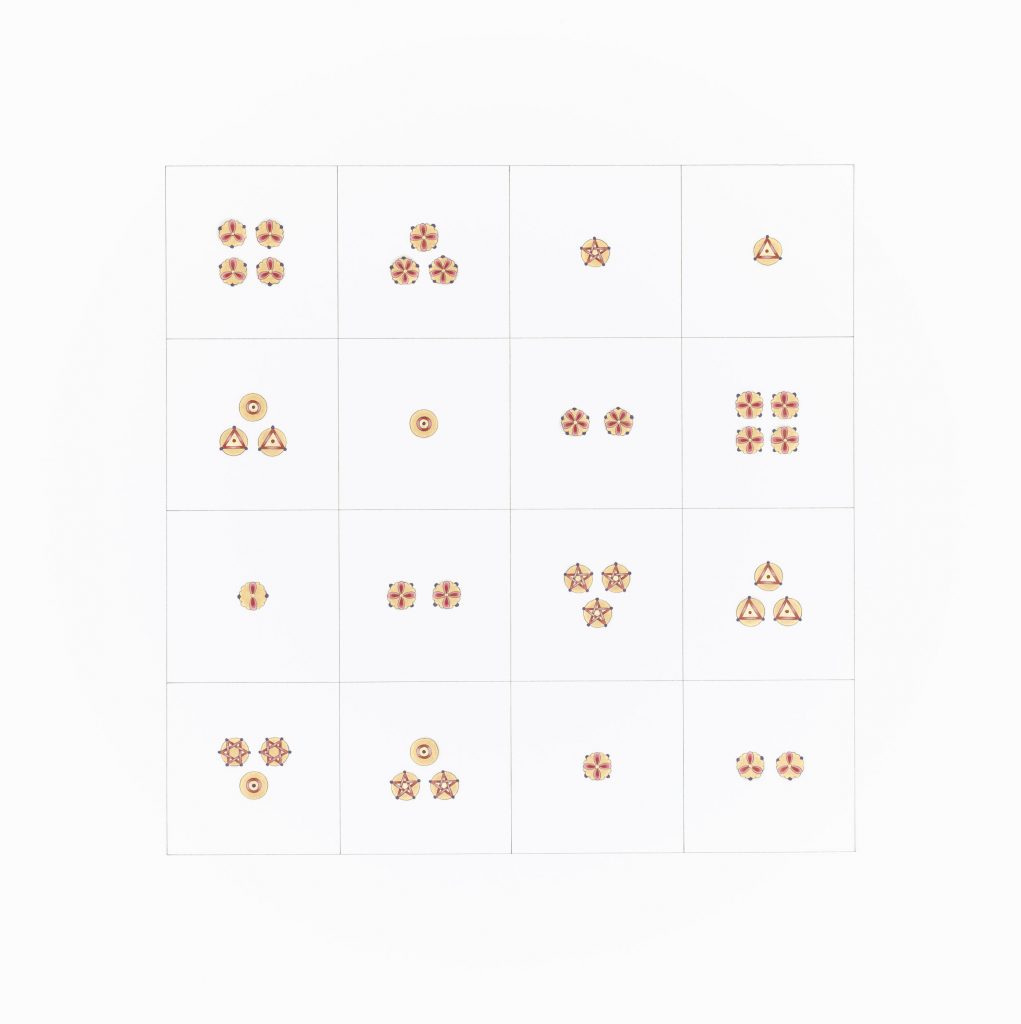

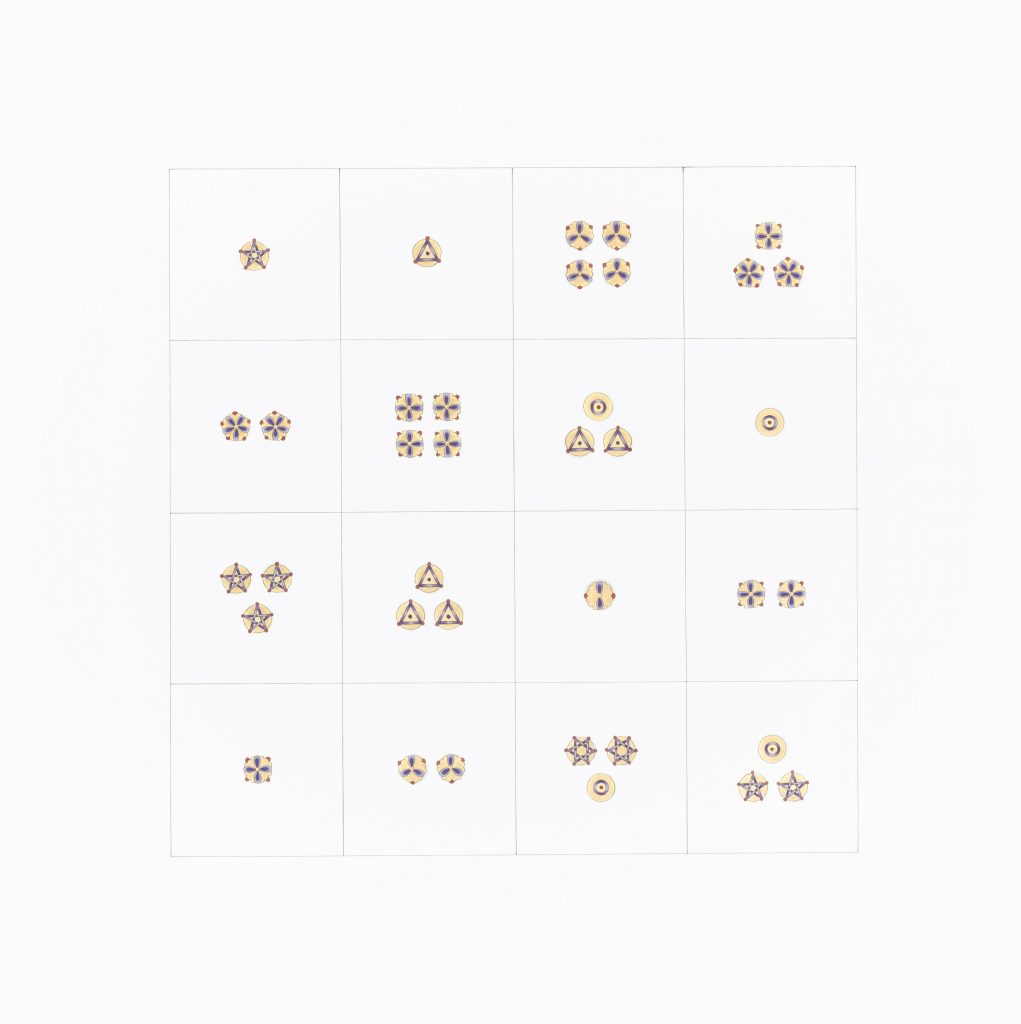

WHEN IT ALL ADDS UP

2015

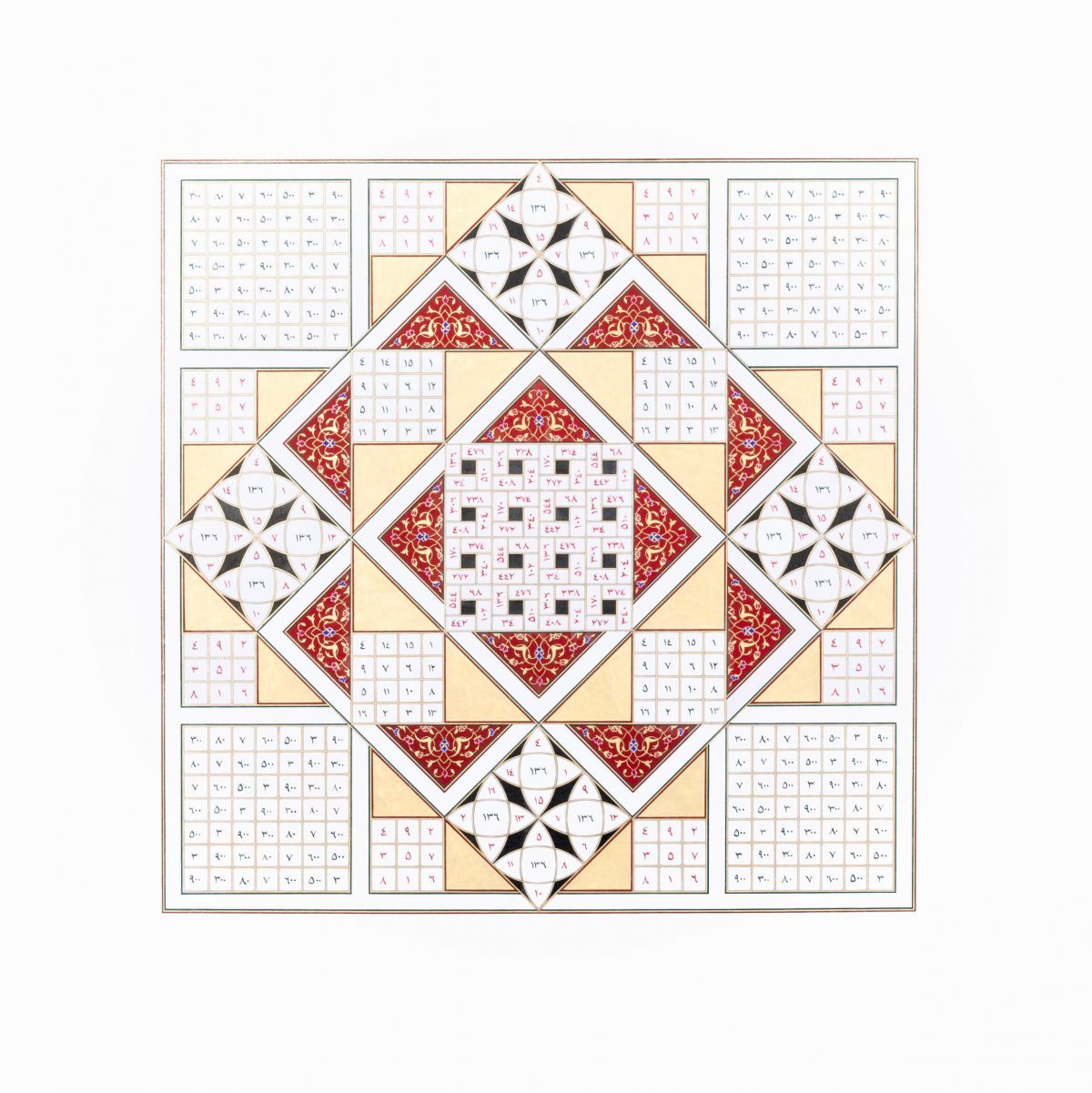

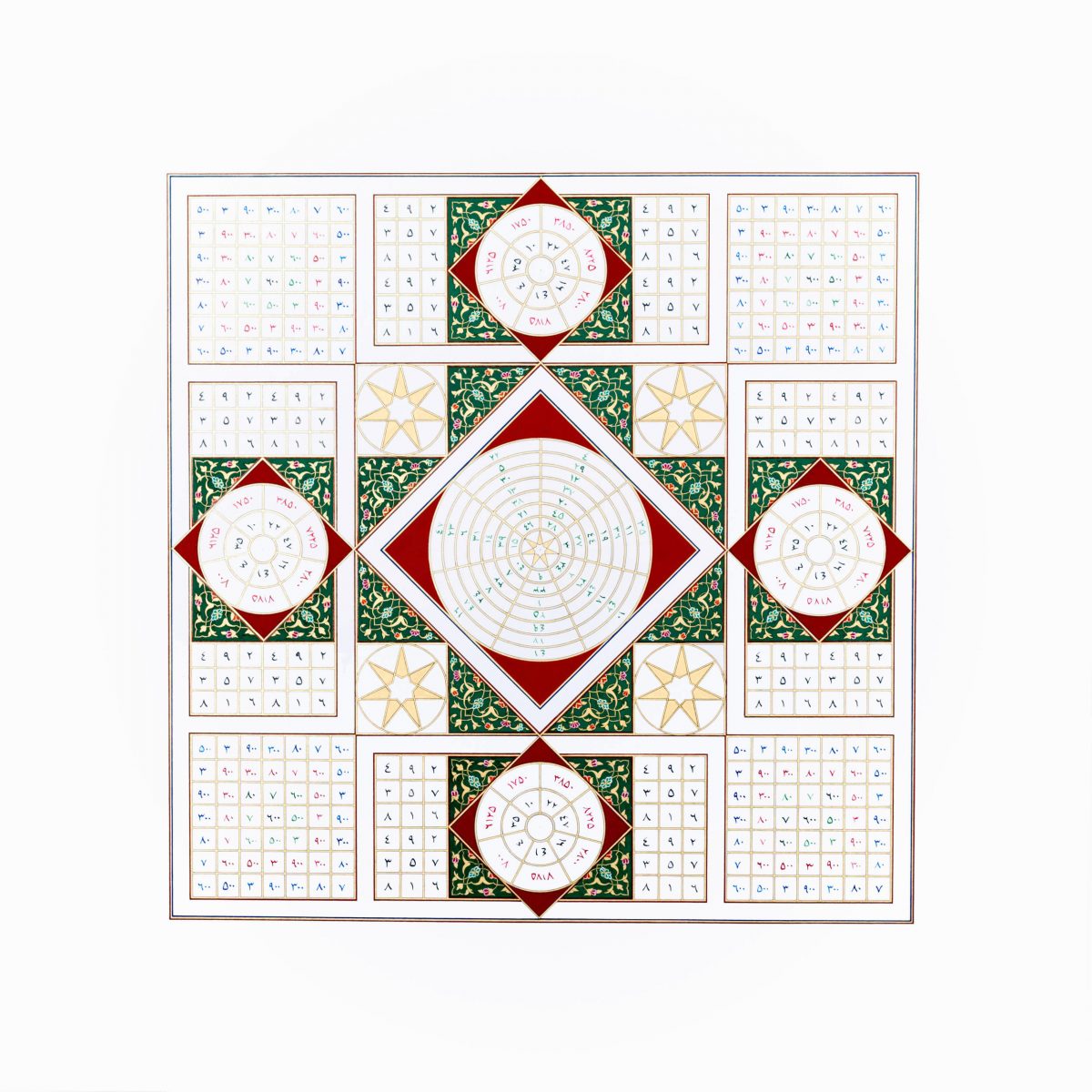

These series of paintings draw upon the mathematical system used in the recreational game of magic squares, to explore questions of femininity and masculinity. Magic squares are based on a ritual once thought to hold mystical properties, with references to the use of magic squares in astrological calculations, a practice that is said to have originated in the Middle East and to be rooted in Islamic traditions. On winning this game, the sum of each row, whether it be diagonally, horizontally or vertically, should always be the same. Awartani has recreated the 4 x 4 magic squares using a geometric code that she has developed in place of the numbers. In Islamic tradition odd numbers are attributed to qualities considered masculine such as rational thought, whereas even numbers are attributed the feminine, for denoting emotional approaches. Due to the fact that God is affiliated with the number 1, odd numbers are more commonly favored and used in Islamic rituals such as the daily number of prayers or the seven turns around the Ka’ba as part of the Hajj. Awartani has developed masculine and feminine symbols, from stars to floral motifs, where the sum of each petal or point in an illustration will directly correlate with the original numbers of the magic squares. The works touch on the question of women’s role within Islam, the combination of geometric and circular motifs, each essential to the resolution of the puzzle, finding their balance and equilibrium within the structure.

When It All Adds Up I, 2015, shell gold, natural pigments and ink on paper, 42 x 42 cm. © Dana Awartani

When It All Adds Up II, 2015, shell gold, natural pigments and ink on paper, 42 x 42 cm. © Dana Awartani

When It All Adds Up III, 2015, shell gold, natural pigments and ink on paper, 42 x 42 cm. © Dana Awartani

When It All Adds Up IV, 2015, shell gold, natural pigments and ink on paper, 42 x 42 cm. © Dana Awartani

When It All Adds Up V, 2015, shell gold, natural pigments and ink on paper, 42 x 42 cm. © Dana Awartani

SCROLL OF THE PROPHETS

2015

The Scroll of The Prophets explores the science of numerology, code making and abstraction of figurative representations. The artwork takes the names of all the 25 prophets mentioned in the Qu’ran and translates them back to their numerical value using the system of Abjad Hawaz; which is a decimal alphabetic numeral system/alphanumeric code, in which the 28 letters of the Arabic alphabet are assigned numerical values. It has been used in the Arabic-speaking world since before the eighth century when positional Arabic numerals were adopted and has been used for multiple purposes including mysticism and numerology.

Using this system, Awartani has converted each of the 25 names into their numerical value and then constructs a geometric pattern for each prophet based on their number, layering the circles, squares, stars, triangles and hexagonal forms, placing one character (or individual) next to the other in a chronological scroll.

Within the Islamic tradition figurative representations of any prophet is deeply frowned upon and akin to idol worship, however by adopting the art of geometry, which is a highly common and prized form of visual expression used in the Islamic tradition, Awartani attempts to transcend the limitations placed on representational forms and reimagine alternative methods of expression.

Scroll of The Prophets, 2015, gouache and ink on paper, 42 x 681 cm. © Dana Awartani

WITHIN A SPHERE

2015

Within a Sphere 4, 2015, Pen, shell gold and natural pigments on paper, 73 x 73 cm. © Dana Awartani

Within a Sphere 6, 2015, Pen, shell gold and natural pigments on paper, 73 x 73 cm. © Dana Awartani

Within a Sphere 8, 2015, Pen, shell gold and natural pigments on paper, 73 x 73 cm. © Dana Awartani

Within a Sphere 12, 2015, Pen, shell gold and natural pigments on paper, 73 x 73 cm. © Dana Awartani

Within a Sphere 20, 2015, Pen, shell gold and natural pigments on paper, 73 x 73 cm. © Dana Awartani

PLATONIC SOLIDS

2014

The Platonic Solids are a series of paintings based on Euclidean geometry which is the ancient study of shapes. In their 3 dimensional form they are the most frequently studied shapes in history and they have been around for thousands of years, geometers have studied their mathematical properties and been fascinated by their inherent beauty and symmetry. What makes them particularly important is that they are considered as the only five ‘perfect’ shapes in three-dimensional space that derive from a sphere. They appear the same from any vertex, their faces are made of the same regular shape, and their vertices represent the most symmetrical distribution of the numbers four, six, eight, twelve and twenty on a sphere.

Awartani has taken direct inspiration from these forms and has translated these three-dimensional shapes into two-dimensional paintings through their essential geometric principles. Each painting is based on the numerical value of the individual vertices of the platonic solids and the colours used are directly inspired by the four elements (earth, air, fire, water) and the heavens that Plato has attributed to each shape.

Tetrahedron from the Platonic Solids series, 2014, Pencil and natural pigments on paper, 81 x 81 cm. © Dana Awartani

Octahedron from the Platonic Solids series, 2014, Pencil and natural pigments on paper, 81 x 81 cm. © Dana Awartani

Hexahedron from the Platonic Solids series, 2014, Pencil and natural pigments on paper, 81 x 81 cm. © Dana Awartani

Icosahedron from the Platonic Solids series, 2014, Pencil and natural pigments on paper, 81 x 81 cm. © Dana Awartani

Dodecahedron from the Platonic Solids series, 2014, Pencil and natural pigments on paper, 81 x 81 cm. © Dana Awartani

SEAL OF THE PROPHETS

2014

Moses from the Seal of the Prophets series, 2014, Silkscreen, shell gold and gouache on paper, 118 x 118 cm. © Dana Awartani

Jesus from the Seal of the Prophets series, 2014, Silkscreen, shell gold and gouache on paper, 118 x 118 cm. © Dana Awartani

Mohammed from the Seal of the Prophets series, 2014, Silkscreen, shell gold and gouache on paper, 118 x 118 cm. © Dana Awartani

ORIENTALISM

2014

Dana Awartani’s artwork titled “Orientalism” is a room that is covered entirely with patterns that are inspired by both the traditional motifs found in the tribal costumes of Saudi Arabia and “Al Qatt Al Asiri” which is a historic artform of interior domestic wall decoration adopted by the women in the region of Asir.

In Awartani’s installation, she firstly draws the geometric patterns on the surface of the room using the traditional approach of a compass and ruler followed by covering it up with PVC tape. Through this piece she aims to comment on how global modern-day society is obsessed with the “new” and consequently much interest and knowledge of our culture and heritage has greatly diminished and is in danger of dying out.

Rather then using natural materials which is a common thread throughout her artistic practice, Awartani has chosen PVC tape as her medium to symbolize the industrialization of traditional modes of making and how artisanal knowledge is slowly disappearing. As a consequence, the installation is never permanent and cannot be reproduced, once the exhibit is finished Awartani removes the tape and throws it away making the artwork a temporary relic of the past.

Orientalism, 2014, PVC tapped room, L250 x W200 x H230 cm. © Dana Awartani

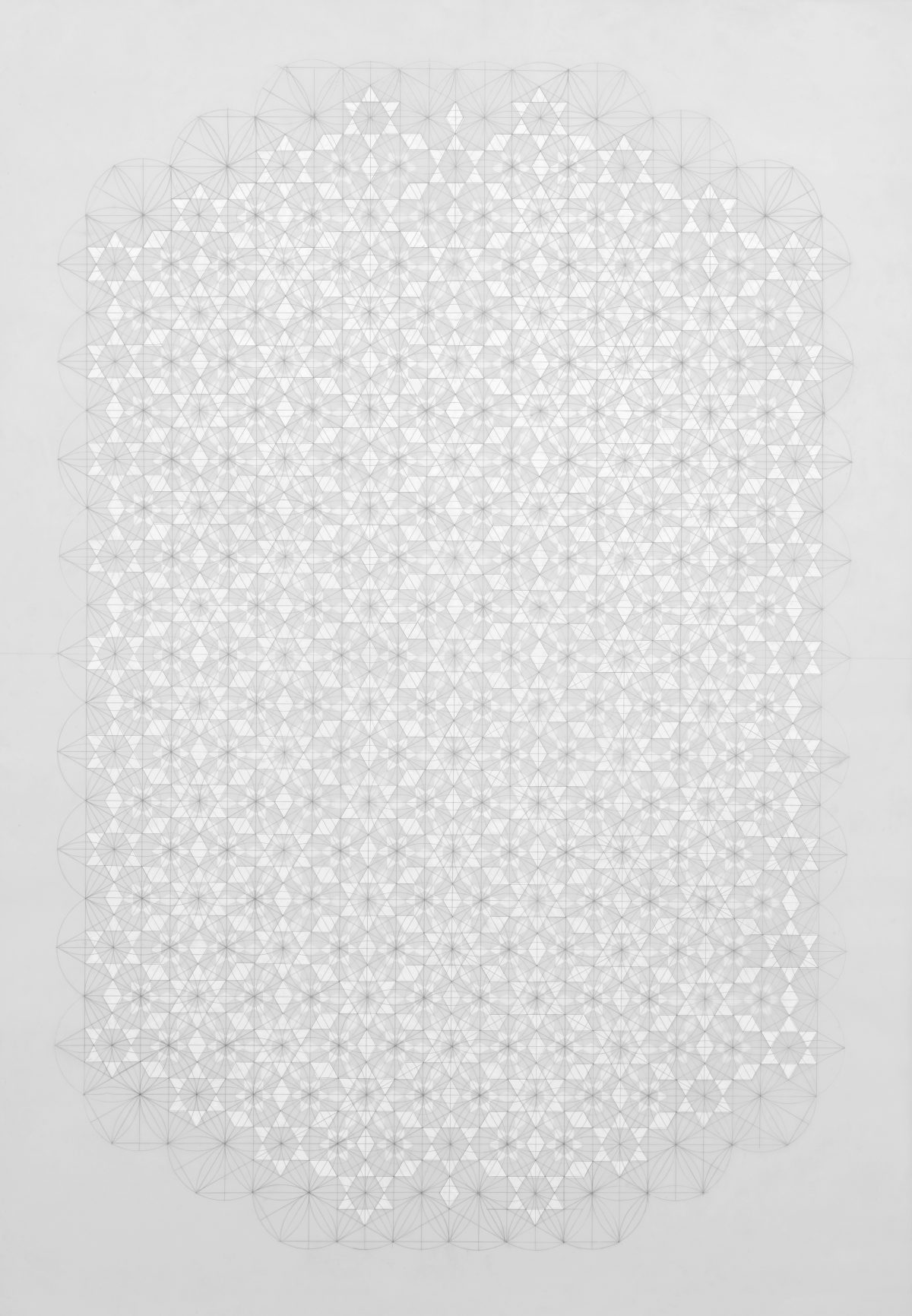

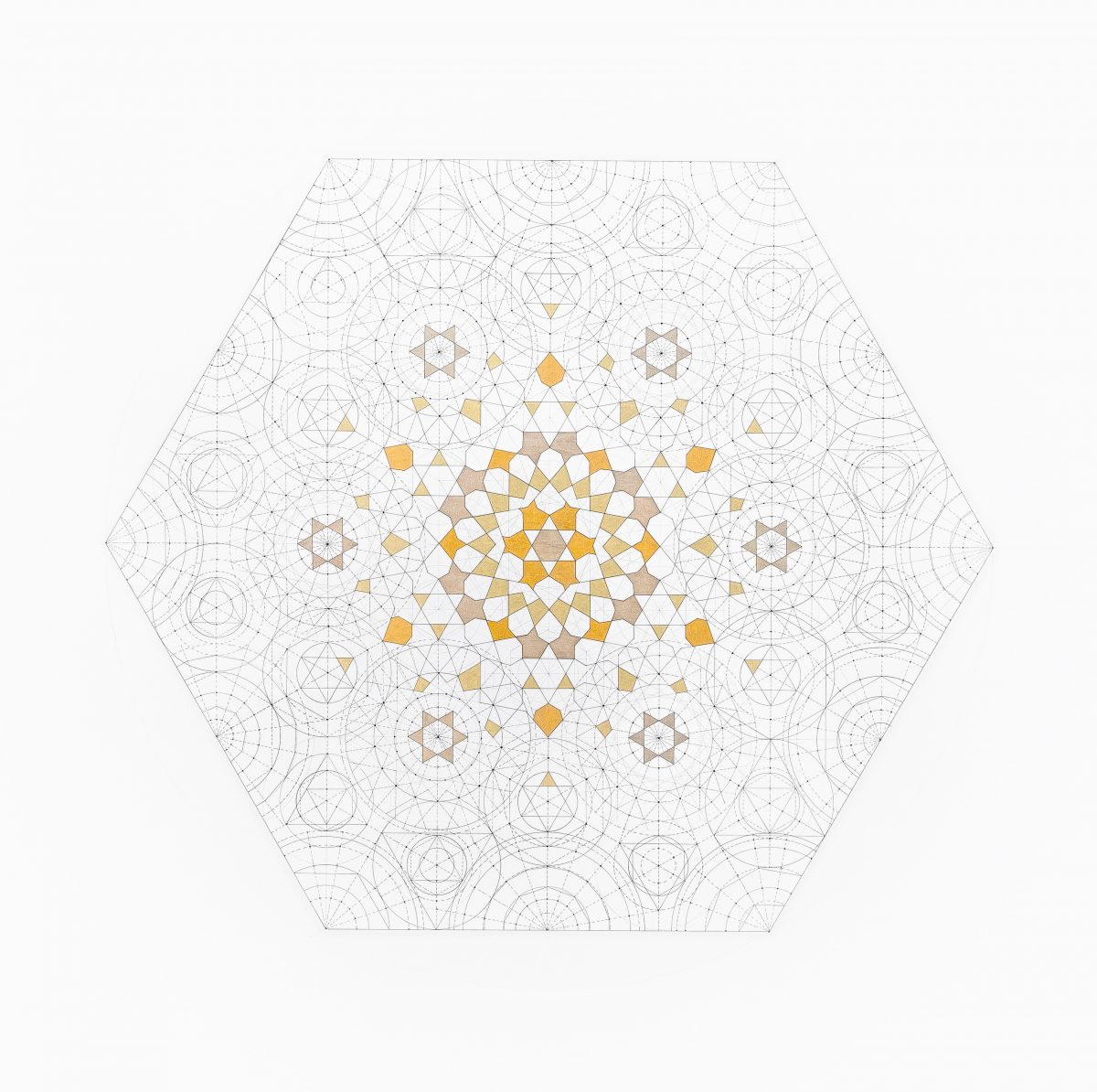

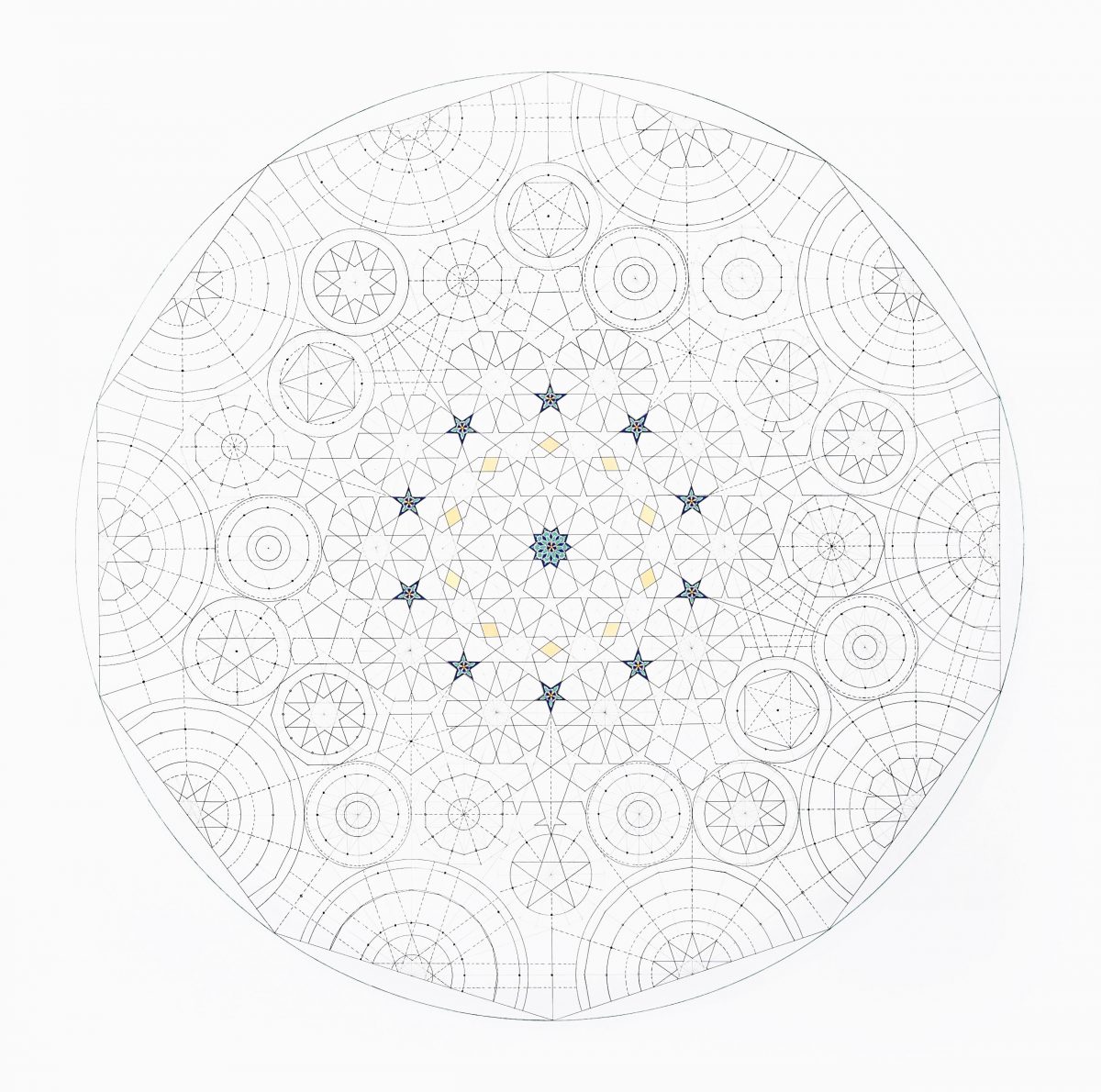

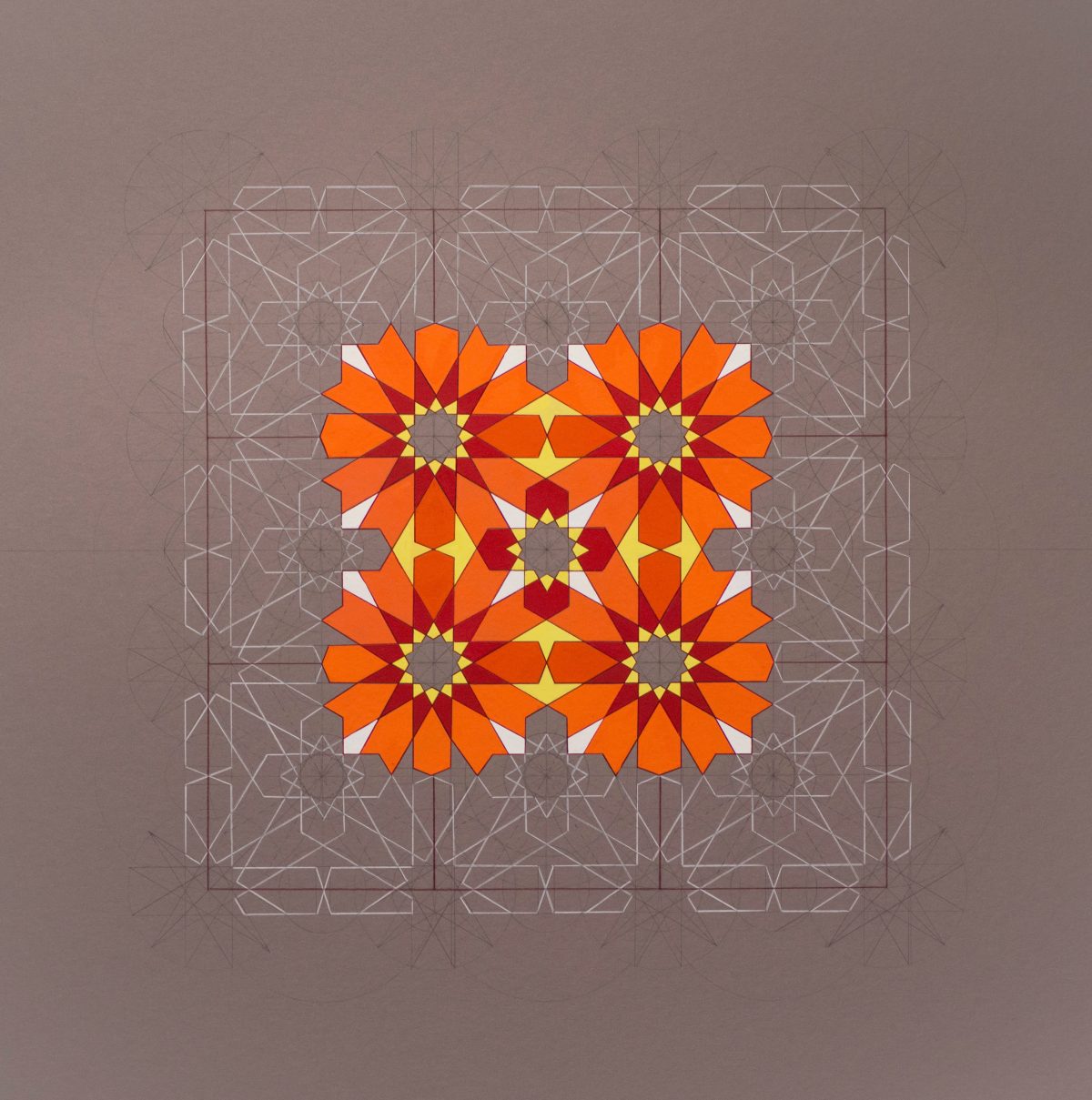

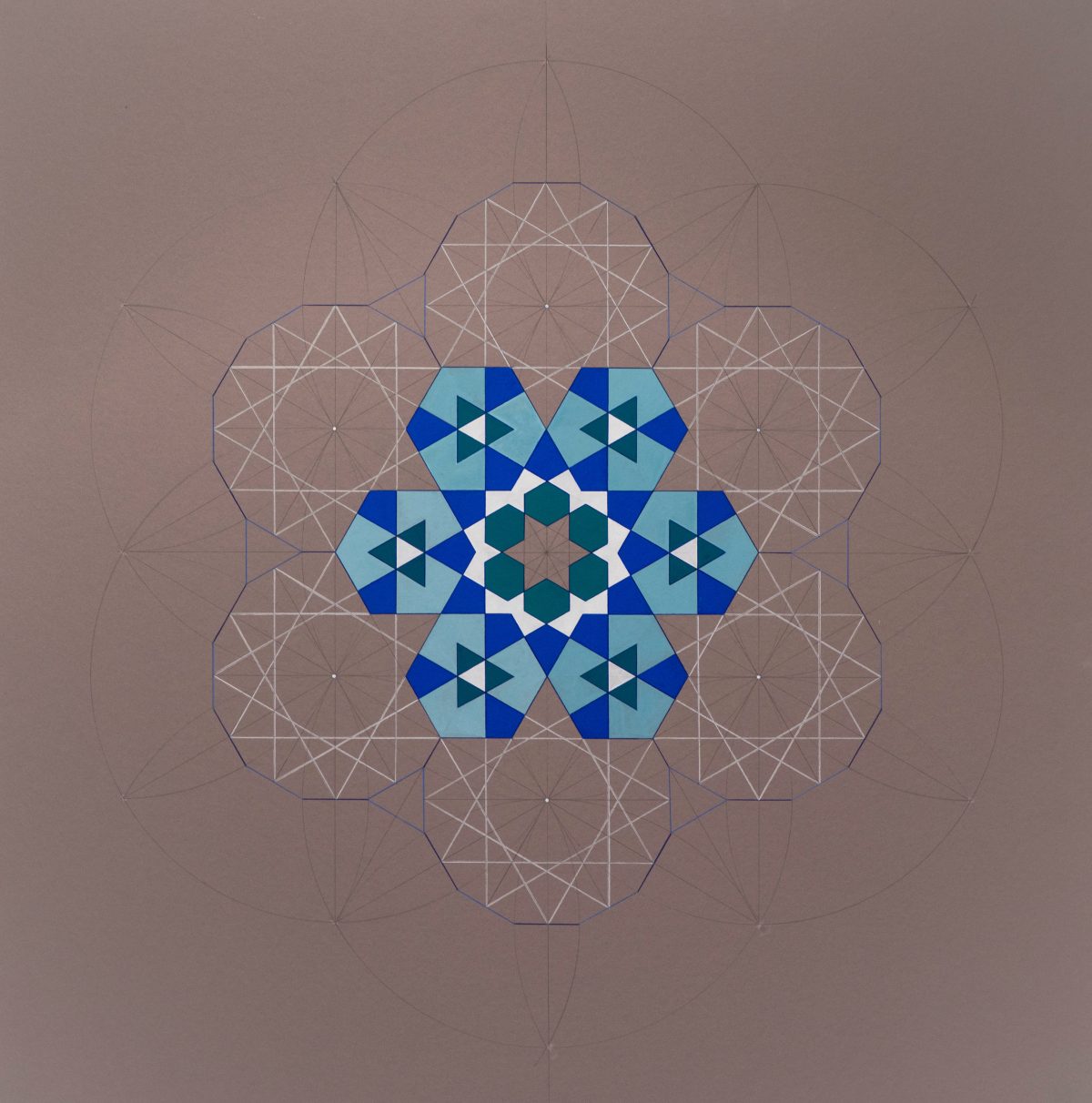

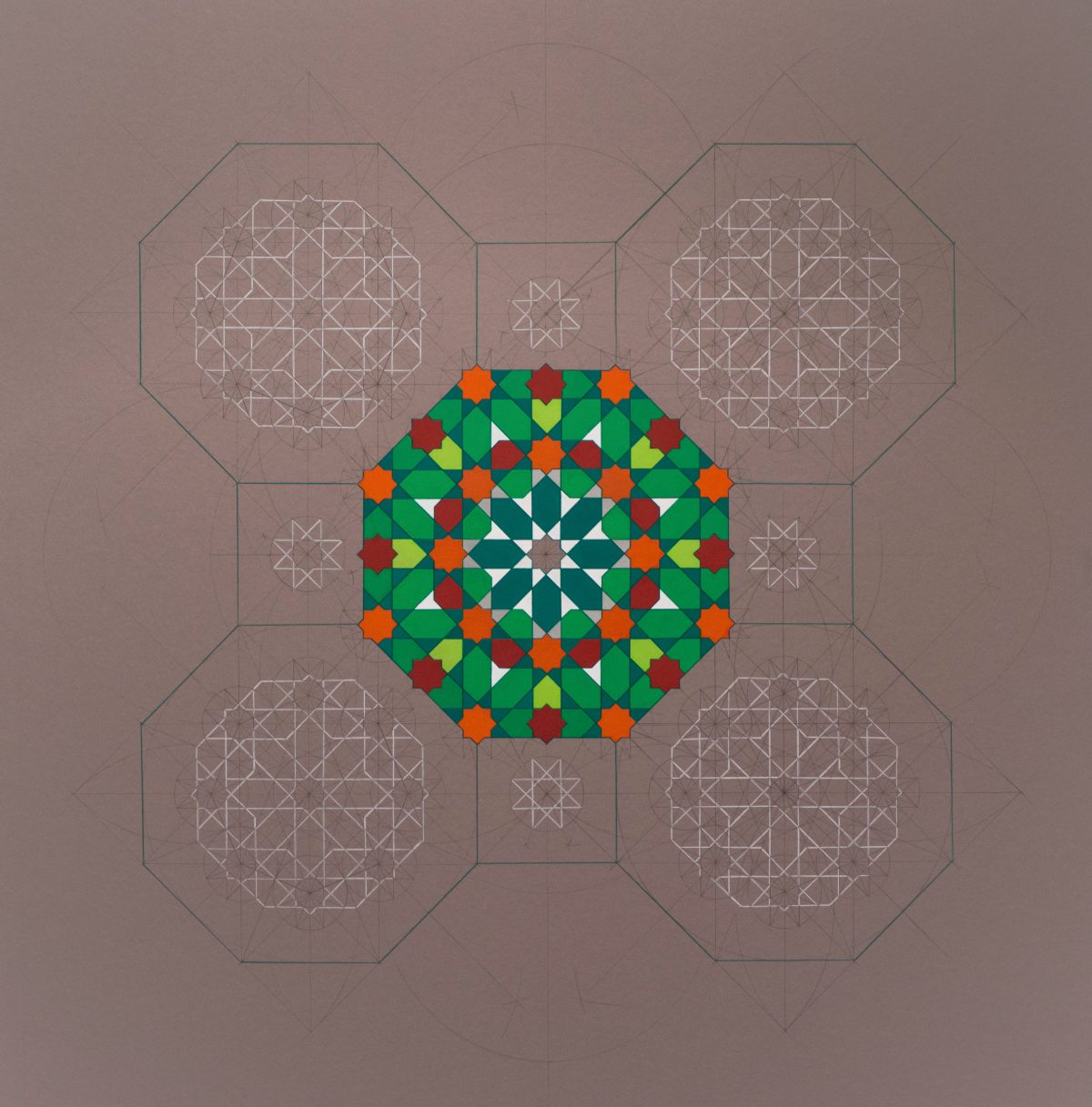

PROGRESSIONAL DRAWINGS

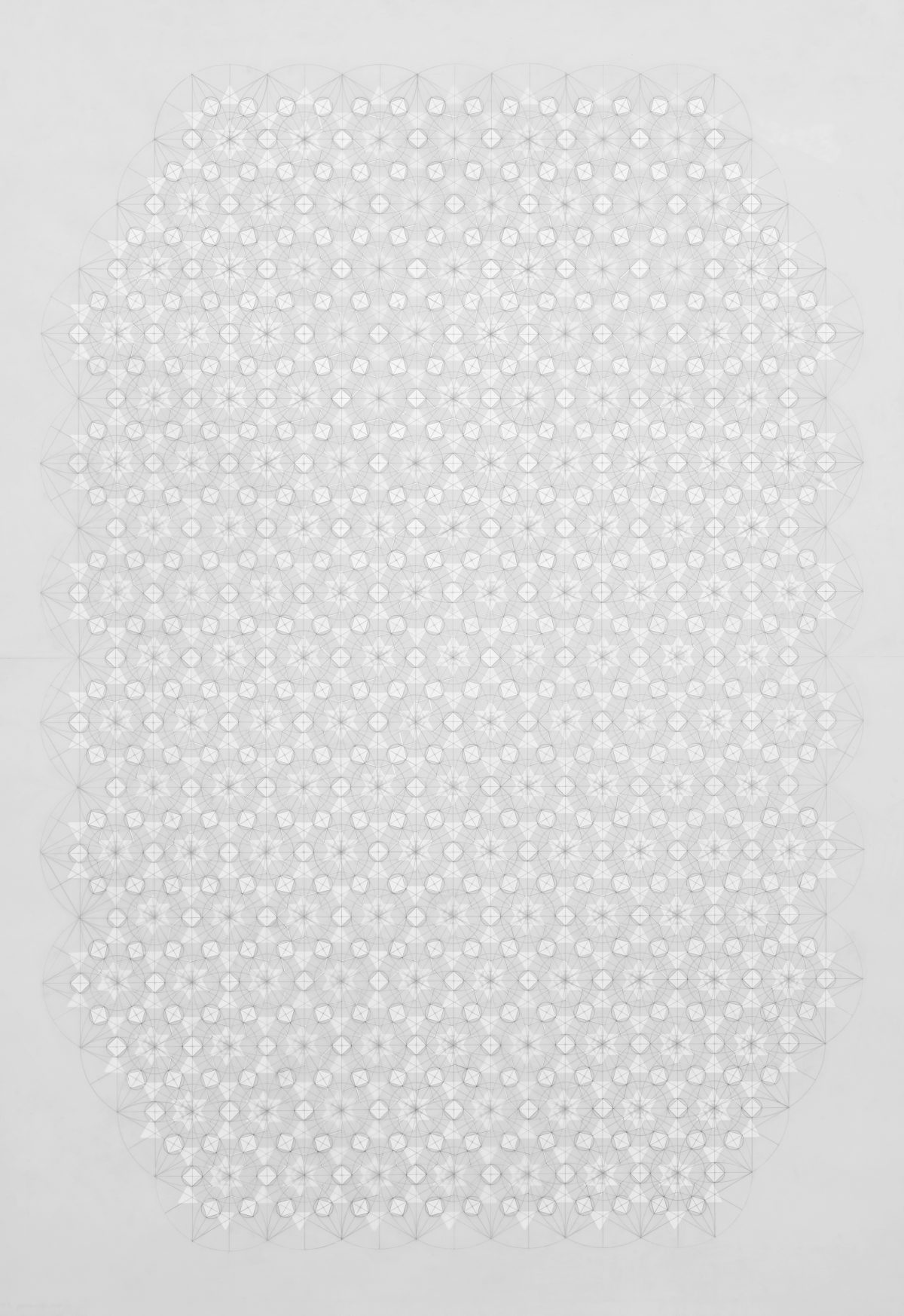

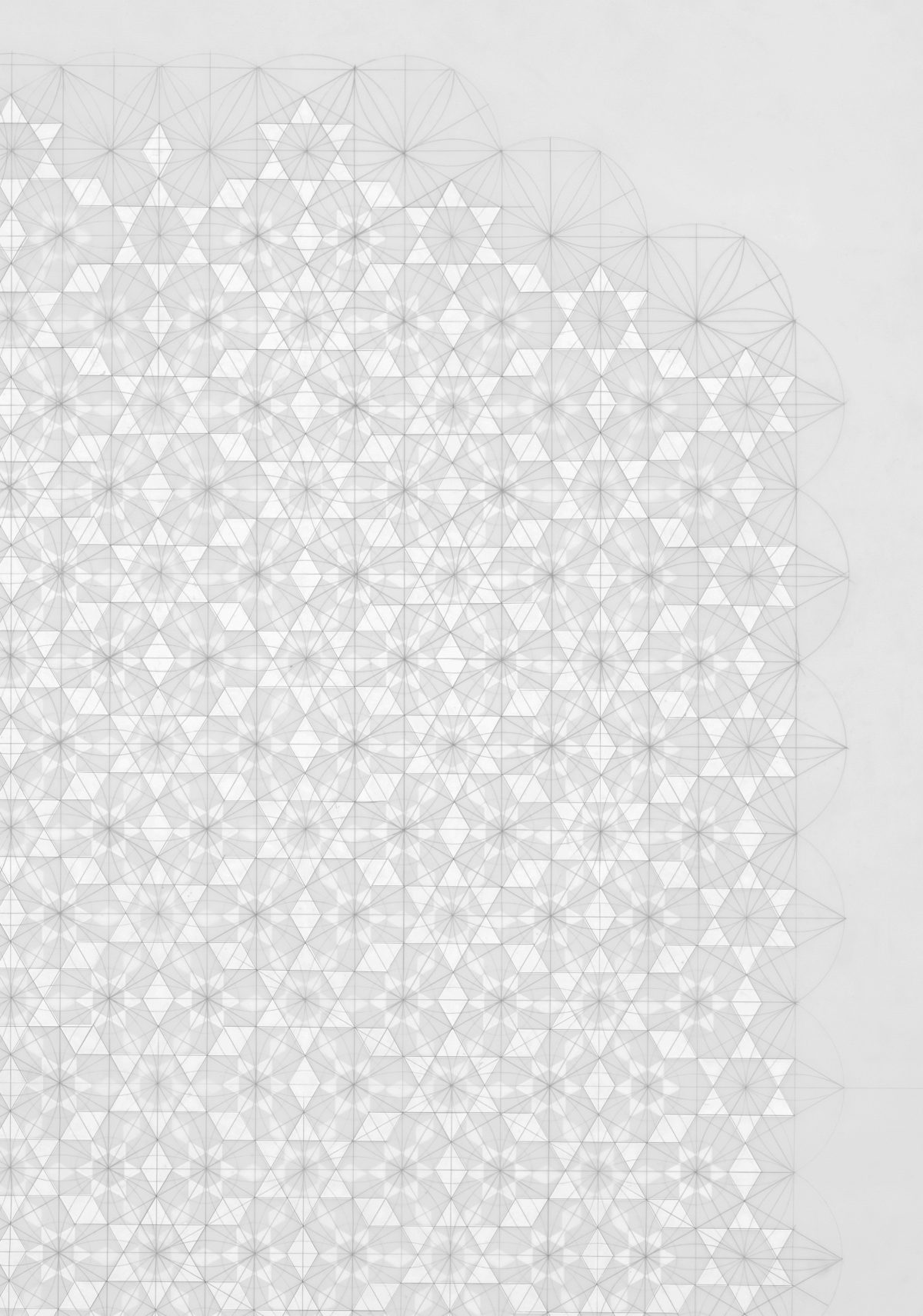

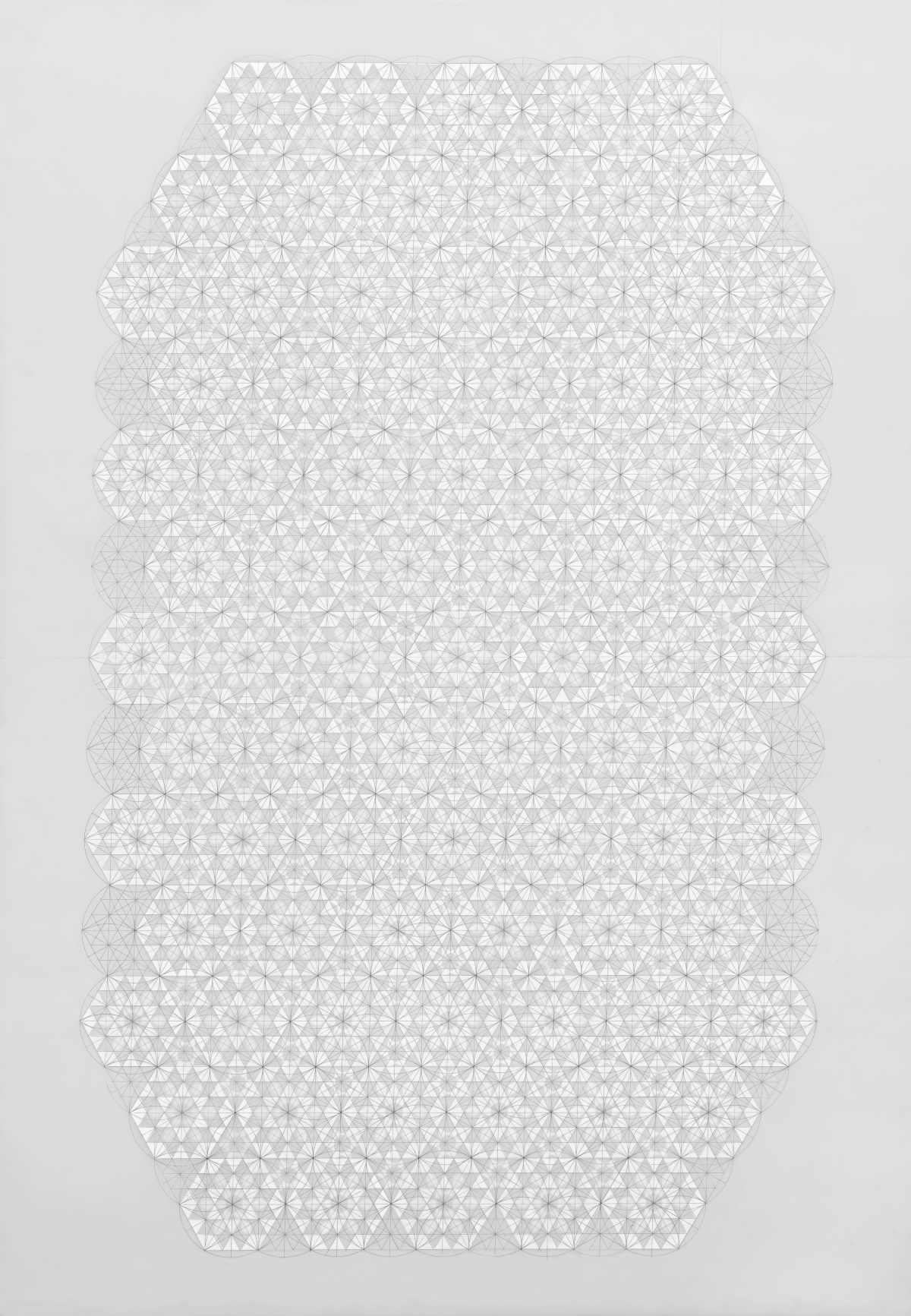

2013 – present

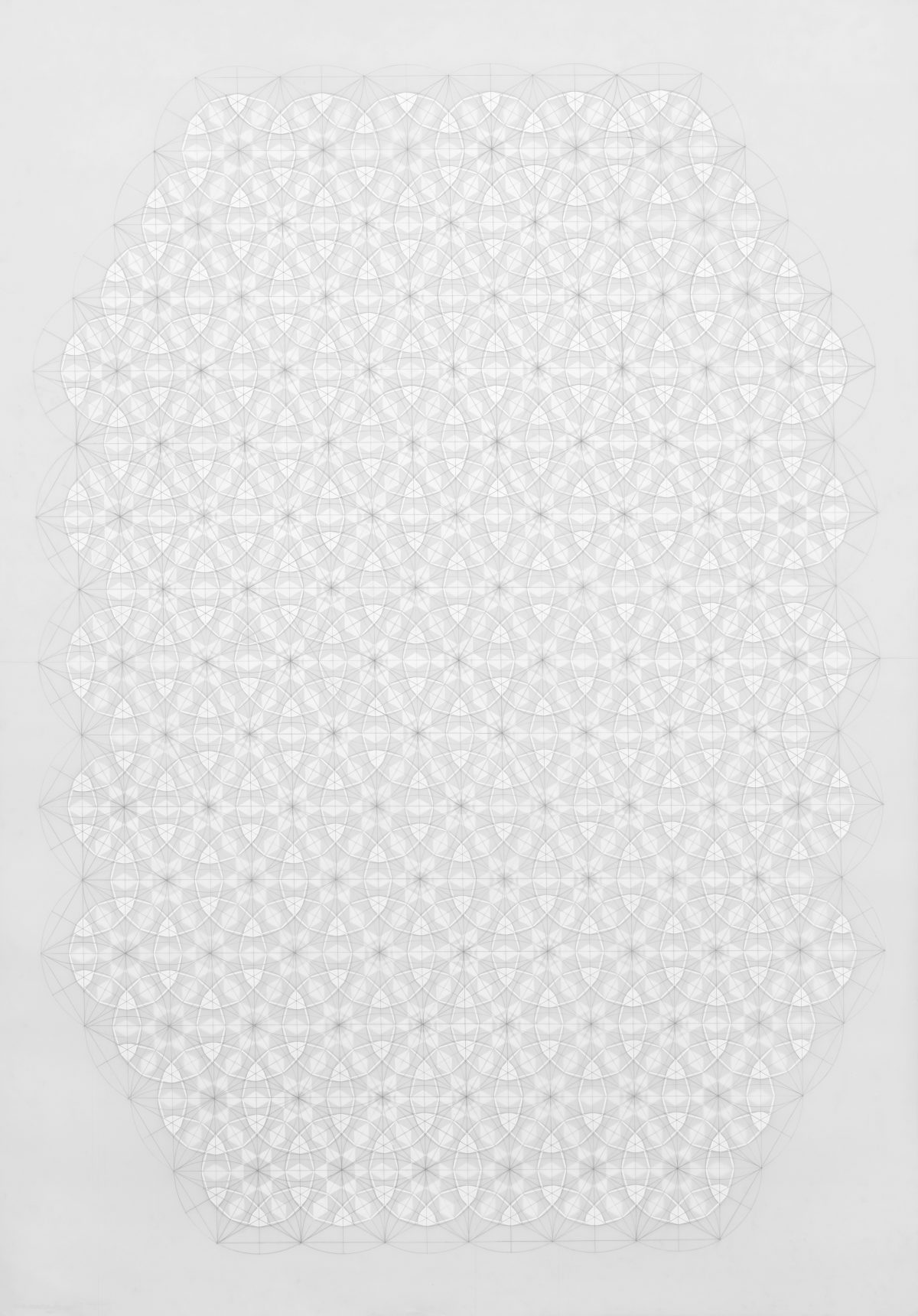

Awartani’s progressional drawings are inspired by the philosophy of Tawhid, which is the Islamic teaching of the Oneness of God. Her drawings begin with a circle, and by use of specific patterns and mathematical principles, develop into complex geometric design that conclude within the circle. Awartani does not perceive geometry as strictly mathematical practice, but also as a reflection of the laws of the universe, instrumental in attempting to understand its depth and meaning.

The circle is a common symbol of the source of all creation throughout various cultures and religions. Ranging from the ancient Egyptian religion where by Ra, the Sun God, is represented as a circle, too the Hindu philosophy where by it represents the spiritual insight of the third eye and in the Islamic tradition which adopts the circle as a symbol of unity and the monotheism of the One God. Parallelly the circle and its centre are the starting point for every geometric pattern and it is with this knowledge that Awartani creates her progressional drawings to emphasise the unity within multiplicity of all humankind, deriving from and returning to the same source. Aesthetically, the drawings vary in style and colour, and are inspired by the different elements: earth, water, fire, air and the cosmos.

HE WHO CREATED THE HEAVENS AND EARTH IN SIX DAYS

2013

Through this artwork, Awartani depicts the story of the six days of creation found within the Islamic teachings through the aid of traditional sacred geometry and illumination. The six panels dually depict the creation story as well as bring to life the highly rigors process behind the construction of an illuminated manuscript commonly found in Qurans and other religious texts.

These Illuminated manuscripts where typically made with the purpose to represent the heavens and the earth through the use of and aesthetic routed in symbolism and numerology. Since the use of the human form is not favoured in Islamic art, craftsmen throughout history have adopted and elevated the use of numbers, geometry,colour and floral motifs as a visual language to translate esoteric ideas. On a parallel level these art forms were used to create abstract representations of God’s creations on earth as a form of worship and spiritual devotion, as geometry can be found both on a microcosmic and macrocosmic level throughout all planes of creation, and when studied is a way to understand the hidden language of the universe.

The design of the artwork has been conceived based completely around six-fold geometry, ranging from the twelve-fold central rosette, to the six boarders encompassing it to the proportion of the whole painting which is based on the route three triangle, all being part of the six-fold ‘family’ found within sacred geometry. The colours Awartani has adopted play an equally important role, as within the Islamic tradition, blue and green are considered to be sacred and reflect water and vegetation both highly rare in desert countries where the religion was founded.

He Who Created The Heavens and Earth In Six Days, 2013, Natural pigments, shell gold and pen on paper, 6 pieces – 62 x 47 cm each. © Dana Awartani