Category: Uncategorized

In Conversation with Dana Awartani: I went away and forgot you

Dana Awartani in conversation with Luisa Duarte for the 21st Contemporary Art Biennial Sesc_Videobrasil.

LD: It would be important to know what “Islamic Ilumination” is all about and how it acts in the video.

DA: This work doesn’t have any islamic illumination which are usually the floral paintings that accompany calligraphy you find on manuscripts. The pattern on the floor is geometry and is inspired by Traditonal ceramic floors you find across the islamic world. Sacred geometry plays an important role in my practice and I use it a lot, its a combination of mathematics, science, spirituality and nature. And the reason for using geometry as the design of the floor in the video is too echo the traditional islamic architecture that was historically used in the region.

LD: It is clear in your work the concern to think the cultural identity of the Middle East and how much we have been missing of it nowadays. Yet, there is a work that involves the construction time of this big sandy carpet, which we haven’t watched and the short time of its deconstruction, operated by you. How do these layers or coatings act in your work?

DA: Well, the reason why I didn’t show the process of how the floor was made was because I didn’t feel it to be important, the sand is part of the artwork and not the artwork itself. It’s simply a medium or tool I used to express a sense of sorrow to the viewers. Also we live in such a capitalistic society that is obsessed with ownership and accumulating objects and wealths, so in a sense letting go of that is the real challenge, destroying something beautiful rather then trying to preserve it goes against everything we are taught. This philosophy is also routed in a lot of spiritual practices, Buddhists destroy mandalas after making them and Hindu ascetics abandon all there earthly belongings to live a simple life in order to attain the divine, so I was inspired by that as well.

LD: Is there a particular concern with the role of the women in this culture?

DA: This piece doesn’t aim to talk about gender roles or anything feminist. I just happened to be wearing an abaya because the work was commissioned by the Saudi art council and was to be shown in Saudi so I felt I should be wearing it. Also the reason why I picked to destroy the sand using a broom is because I wanted to destroy the work in a tender and non aggressive manner, so that the audience could focus more on the act of destruction rather than how I am destroying it.

LD: Tell me more about the title – ““I Went Away and Forgot You. A While Ago I Remembered. I Remembered I’d Forgotten You. I Was Dreaming””- please.

DA: The title was taken from one of Mahmoud Darwish’s poems. I really love his poetry which is usually about Palestine and he writes on the themes of loss, sorrow, dispossession and exile, he is considered one of the most important poets and is referred to as the national poet for Palestine. I selected this specific poem as the title because of the sense of nostalgia it provokes, I am using it as a metaphor to imply that Saudi heritage is so long forgotten and abandoned that hardly anyone remembers it even existed.

In Conversation with Dana Awartani: Come, let me heal your wounds

Dana Awartani in conversation with Myrna Eyad about her newly commissioned work for the Al Burda Endowment granted by the UAE Ministry of Culture and Knowledge Development.

ME: All of your work is made using natural materials.

DA: In recent years, a theme that popped up a lot was the idea of sustainability and living an ethical lifestyle – we live in a harmful way to the environment and we dispose of things very quickly, so I like the idea of repairing objects and this is also why I use natural pigments, even in my paintings. I then wanted to take it a step further by tapping into the meaning of natural dyes. In the Indian and Arab cultures, we used to use herbs and spices as remedies (still practiced in South Asia), but now rely more on Western traditions. I found a Hand Loom Weavers Development Society in Kerala and loved the ethos of how they function – they predominantly hire women from poor communities, they don’t use machines, the leftover dye is used as biofuel, spices and herbs are sourced by local people from the local forest and everything is sustainable.

ME: What attracted you to this process?

DA: The ethics and historical accuracy. The textile industry is responsible for a lot of global pollution. In my dyes, instead, over 50 medicinal plants were used and I like the idea of healing through nature and through textiles. Today, we only apply preservation to carpets, and not to other fabrics or textiles. In India, for example, expensive textiles like Kashmiri shawls take a year to make. If it gets damaged, it would not be thrown it out, but rather, repaired and safeguarded because there is a culture of preservation of textiles. The more I spent time in India, and saw how they cared for fabrics, the more I saw how they defied the lingering legacy of the British occupation, which sadly sacrificed the local hand loom industry in favour of industrialisation. I found it a form of resistance and I love that powerful political aspect to it.

ME: Is it ironic that you have applied plants that have healing powers to a concept that is about destruction?

DA: I believe that answers can be found in nature and that nature is the best teacher, but I also value the ancient knowledge encapsulated by these textiles and healing cloths. For example, maybe they can help someone grieve and studies have shown that they do help people with physical ailments. Some of the plants in my piece include turmeric, holy basil, aloe vera, henna, jasmine, pomegranate and lotus, all of which have cultural references.

ME: What are some common denominators between this piece and previous ones?

DA: The meditative aspect is really true for all of my work. My practice is inspired by traditional art, which is incredibly laborious; you have to do it over and over again. The illumination that I do, for example, takes months. Though I like to change medium a lot, the meditative aspect is always rooted in every piece I do.

ME: How did your interest in textiles develop?

DA: It began during my participation in the Kochi Muziris Biennale, it was there where I first had the opportunity to collaborate with embroiders from Ahmedabad and have continued ever since. More specifically my interest in ‘ratta’ or more commonly know as darning in English which i am using in this piece, came about when one of my previous artworks had a tear in it and as I did not know how to repair it, I had to remake it. Now that I have learnt more about preservation and darning, it opened a whole new chapter in my work with textiles.

ME: Your previous work focused on spirituality and history. Recently, there has been a shift to cultural destruction. How did that happen?

DA: I have been interested in it for the last few years. While I do not consider this work some sort of grandiose solution to heal the Middle East, it is, however, about how I, as an artist, see our collective history being destroyed. I am not just a Saudi, or a Palestinian or a Syrian; I am Arab. I cannot identify with any one nationality, and I think this multicultural aspect to me is my strength because I care about the whole of the Middle East and not just one country. My work addresses themes across the Arab world and focuses on cross-cultural dialogue. India is included because our histories have intersected, especially through trade.

ME: You want to show the pain.

DA: Exactly. There is a lot of pain. I want to induce a feeling of sympathy, in that I want people to feel pain, but not in a hostile way – in a poetic manner. I think it is more effective to take the audience by the hand and lead them. Confronting people aggressively is repellent and can only create limitations. I have to find more subtle ways of communicating ideas.

ME: How did you decide on the aesthetics and colours?

DA: Seven countries are represented here – Syria, Iraq, Yemen, Libya, Tunisia, Egypt and Saudi Arabia. The countries with the most cultural destruction (Iraq, Syria and Libya) were divided into two panels each and there are 10 panels of different sizes in total. I used several colours for practical purposes and depth; they are also all found in nature (red, yellow, orange and green). I want people to come close and walk in amongst the textiles so they can smell them and see the detailed embroidery.

ME: How does this correspond geographically?

DA: The intention is not to identify the countries by looking at the textiles. I did a lot of research into the destruction of monuments, looking at sites before and after. I distributed it by country, looked at the cities, pinpointed where each monument was (or had been) and put a dot where each was destroyed. I created multiple printouts and had architectural sheets made to abstract the locations. So, while I can point the countries out to myself, I specifically did not want this to look like a map. I feel that that is so overdone. This meant no borders or countries, it had to be abstract. The dots rendered here are in different sizes purely because of the design I wanted, not to denote the gravity of destruction: a destroyed monument is a destroyed monument. The physical scale doesn’t matter.

ME: Sadly, this is an ongoing piece in the sense that cultural destruction will continue to happen.

DA: Yes, the destruction by many different terrorist groups begins with the Arab Spring and carries all the way through to August 2019 in this piece. I am hoping there won’t be more. I hope it is now about rebuilding.

ME: The way to eradicate a civilisation is to destroy its culture.

DA: Absolutely. Not only do so many in the West not know about our rich, pluralistic society, many in the Arab world are unaware too. I don’t want to be nostalgic and think of the past, but this is one the darkest times in our history as Arabs. We need to re-educate, preserve and shift attitudes about what is important in our cultures. Our people feel their culture is inferior in comparison to the West.

ME: How do you get people to take pride in their roots?

DA: First and foremost: education. When I was at school in Saudi Arabia, there was nothing in the curriculum about Arab history, which means there is almost no way for younger people to engage with our countries’ past. Another very important aspect is stability: the West prospers because of stability. We don’t have that here because we are focused on survival. Also, one can learn so much from working with craftsmen. Look at calligraphers and illuminators – historically, they were taken in by the royal courts and had patrons support there work. One wonders what will happen to the now-refugee master craftsmen of Syria and Iraq. I feel like today, it’s on us, the younger generation to be involved and I see more taking an active interest in our culture. Hopefully, this will have a ripple effect.

ME: How is this work a departure from your previous pieces?

DA: There are a lot of firsts in this work – it marks the first time I use colours in my textile s, the first time I actually embroider myself, and the first time I have not used geometry or floral motifs. It is quite liberating. As a young artist, I am at a stage where I can play with different things and not be limited to any one medium and aesthetic. Conceptually, the work is tied to Islam in that it looks at cultural destruction in the Middle East committed by Islamic fundamentalists, and some of these ruined sites include mosques, shrines, churches as well as pre-Islamic sites.

Geometry

Contributing text by Professor Paul Marchant about the artist’s ‘Platonic Solid Duals series’ written for the 6th Marrakech Biennale.

The meaning of the word ‘Geometry’ is not limited to the dictionary definition of ‘earth measure’. Traditionally it refers to the central law that accords to the essential rhythm of the universe; it is the source of harmony, balance, beauty, proportion and is the reflection of the true aspect of all phenomena manifested in nature.

The study of geometry is based on springs from ancient civilizations including those of China, India, Africa and Greece. Their practices, in the context of the highest and innermost aspirations of civilization combine the three aspects: wisdom, courage and compassion expressed as physical skill, social understanding, cultural endeavour and spiritual awareness.

A very important handing on of knowledge enabling the contemporary practice of traditional geometry is the transmission of Pythagorean philosophy and teaching of ancient Greece based on sacred number. This tradition is further interpreted in Quadrivium of Plato’s Academy, which taught: arithmetic (number), geometry (number in space), harmony or music (number in time) and astronomy (number in space and time); these are universal languages that underlie all the world’s great traditions.

The scholar Seyyed Nasr describes the relation of the Greek and Islamic traditions as follows: ‘…There is within Islamic spirituality a special link with qualitative mathematics in the Pythagorean sense, a link which results from the emphasis upon unity and the intellect (al-‘aql) on the one hand and the primordial nature of Islamic spirituality on the other. It is not that Islam borrowed from the spiritual significance of mathematics from Pythagoras, Plato or Nicomachus. These ancient sages provided providentially a sacred science which Islam could easily assimilate into its world view. The truth is that there was already in the Islamic world view before its encounter with Greek science what one might call an ‘Abrahamic Pythagoreanism…’ Seyyed H. Nasr, Islamic Art & Spirituality

Geometry is made up of timeless archetypes: point, line, plane, regular polygon, regular polyhedra etc. These are essential elements that form the basis of the study of traditional geometry and encompass: the language of pattern, composition, structure and architectural proportion. The rigorous task of the student of geometry is to deepen their knowledge of the subject; to develop their ability to analyse its grammar and structure. Using the analogy of learning a language, the student must be able to: identify letterforms, understand the meaning of words, construct sentences, write paragraphs and compose a dissertation. They are responsible for the translation of what might be termed the Creative Principle into art design, architecture etc.

At the heart of geometry lies the circle, symbol of unity and the infinite ‘whole’ and mother of all shapes and forms. If the Creative Principle can be symbolised by a point then the relation of various beings to it as Pure Being, is like innumerable points on the circumference drawn about a centre of a circle; their relation to the centre is like that of the various radii from the circumference to its centre. The cosmos can be visualised as the circle, each part of it lies on the circumference which is a ‘reflection of the centre’ with each part connected directly to the centre by a radius, which symbolises its relationship to the Creative Principle.

Thomas Merton gives a fresh insight to the relevance of traditional creativity: “…Tradition is not passive submission to the obsessions of former generations, but a living assent to a current of uninterrupted vitality. What was once real, in other times and places, becomes real in us today. And its reality is not an official parade of externals. It is a living spirit marked by freedom and by certain originality. Fidelity to tradition does not mean the renunciation of all initiative, but a new initiative that is faithful to a certain spirit of freedom and of vision which demands to be incarnated in a new and unique situation…” Thomas Merton, Contemplation in a World of Action

The artist on view has achieved a fine series of very accomplished works in the field of geometric arts inspired by the greatest exemplars of Islamic art. However they are not copies but fresh interpretations informed by hard won discipline and effort to achieve a great depth of understanding of traditional geometry, requiring synthesis of: knowledge, technical skill and enthusiasm to develop awareness of its spiritual dimension.

Paul Marchant

The Silence Between Us: Poetry and Light in the Work of Dana Awartani

Curatorial essay written by Laura Metzler for the Artist’s solo show at Maraya Art Centre.

The Silence Between Us is the first institution- al solo exhibition in the Middle East of Pales- tinian-Saudi Arabian artist Dana Awartani, and aims to delve deeper into her practice and her interest in connecting these traditions with the contemporary moment. Known for her focus on the revival of traditional craftwork and the thorough foundation and focus she has developed through her training in traditional Islamic arts. The artist invites the viewer to trace her path between darkness and illumination, among screens and poems, and to explore the dimensions and layers of meaning she had rendered across series; from the conceptual to the structural, from the traditional and spiritual to the social and the scientific.

On the most formal level layering is a strategy that is activated across all of the works. Layers function in different ways: physically, sensually, conceptually, historically, and spiritually, working with light and as such also with shadow and space to continually shift between the stability of craft and the tentativeness of their forms. Awartani’s renderings have the feeling of the familiar and the tradition of their methods, but also a delicate sensibility of something that could easily slip away. The artist honed this tension through training across different schools of thought; the conceptual sculpture program at Central St. Martins, and the craft study at The Prince’s School of Tradi- tional Arts as well as with her study in Istanbul with a master towards earning her Ijaza honor, a signifier of the mastery of illumination.

Layers are built up or suspended, they morph, distort or screen. Yet they also allow the art- ist to reveal and develop different threads that move throughout her practice. They allow a dialogue between genders, between the soul and the divine, between generations, and among nations. Layering marks the changing of time and the movement of ritual, evoking silences in history and societal memory asking us why those silences remain undisturbed and whether those silences are tense or companionable, or both.

The exhibition itself becomes part of the con- versation, starting and ending at the same point and becoming its own cycle. As the viewer experiences the work they move from darkness into full daylight before slipping back into shadow once more.

In this trajectory, the opening and closing piece is Awartani’s installation Listen to My Words (2018) which draws inspiration from the Jaali screens found in architecture across the Islamic World. They regularly were used in palaces and homes to both create privacy for the inner spaces and to allow air to move through the building by essentially creating a series of small wind tunnels. They are an important meeting point for the public, masculine space, the zahir and the feminine internal space, the batin and were mechanisms also that allowed women to see what was happening in the spaces around them but to be shielded from the male gaze.

The installation consists of seven screens, each with three, stretched, hand-embroidered silk panels that overlap and, when lit, come alive and combine to create an intricate, com- plete pattern inspired by the jaali screen. Each has a unique final composition, utilizing six-fold geometry that was inspired by the jali’s in Mughal architecture in India where the artist collaborated with craftsmen to make the panels.

Women’s voices move throughout the space, reading poems by female poets of the Arab world across time, from the Jahaliyya period through the 15th century, and across the largest geographic boundaries of the Islamic empires. Awartani ties these voices to the idea of the screens and their obscuring function, leaving the women faceless and anonymous as their words ring out.

Female poets have until very recently been regularly left out of the story of Arabic literary history and literary history at large, being the subjects of only a few anthologies and studies. As such much of the information and stories about the women themselves and the circumstances of their writing having long since been forgotten, ultimately ending up shielded not only from the literal male gaze but also the gaze of history, including that of generations of women who have followed. These poets have in essence melted into the screen and become reduced to its flattened interpretation. Contemporary Saudi Arabian women lend their voices to the piece, turning the installation into an impossible salon across time and space as the poems read out, and all are heard. The verses have a wide ranging scope but are largely empowering, focused on the agency of the women. It challenges the re- duction of the history of women to these archi- tectural features, and the sole reading of their roles through the ideas of visibility.

The following two, newly commissioned pieces carry on this conversation. In To See and Not Be Seen (2018) Awartani uses the same six-fold geometric pattern of triangles and hexagons, but rather than confronting the visitor directly as an architectural feature she inverts the pattern and renders the negative spaces in hand-blown and cut prisms of glass. They hang from the ceiling, what otherwise would be the interior space stretches down and capturing the light in an otherwise dim space. Rather than maintaining the perfection of the pattern, the work is lit at an angle, distorting the presence of the imagined screen and denying its form to take hold while still always holding the potentiality for its formation in the perfection of the calculation.

In Diwans of the Unknown (2018) the format changes from a single panel to shrink into three folding silk accordions that evoke folding books. Each is embroidered with progressing patterns and overlap, referencing Listen to My Words but without the finality of the framing. Across the length of the work the poems ref- erence in the earlier fade in and out across the surface, creating shifting, subtle imprints in shadows across the wall behind it. The work is an elaboration/exploration/extrapolation of the idea of the Jaali and what other systems are implicit in the historical silences but also provides an intervention on a personal scale, allowing the poems to literally illuminate the pattern and to draw the viewer beyond.

As the viewer continues the daylight increas- es, coming from a set of windows at the far side of the gallery, casting a gradient across the space and a contrast to the room that holds Listen to My Words.

Rather than continuing the conversation with the screens the work shifts to formal mathe- matical considerations in the artist’s Platonic Solid series, including five sculptures and their corresponding drawings. They reflect her strong traditional training in geometry and tra- ditional craft, the drawings being carried out in a methodical and meticulous manner with her own hand, and the sculptures through close collaboration with artisans.

The artist has rendered and reconsidered geometric forms that have been a source of philosophical speculation since the days of Plato himself. The forms are convex polyhedrons in which all sides and all angles are exactly equal, and are the only possible forms with this trait. Working with craftsmen in India, she has built the pieces physically with an outer form in glass, holding within their core their reflective partner shape, on copper wires, creating a moment of suspension across the five pieces. The sculptures also take into account the physicality of the materials and the traditions of geometric renderings, the centrepiece being made of handcrafted wood working, with the glass utilising tin welding techniques. Wood has a philosophical connection through geometric history, being attributed as the only material that needs each of the elements that are associated with each of the forms to survive; fire, water, air, and earth. The glass reveals this core but a tension and a freezing is undergone in this revelatory process through the internal contours of the copper, literally suspending the wood structure as they stretch between anchors. It creates an architecture of these layers and a form in and of itself, frag- mented through the hooks that they wrap into in contrast to the perfectly formed edges of the dialoguing structures. The patterns warp and stretch slightly as they all collapse in the shadows that creep across the plinth.

Facing the platonic solids, Awartani’s Untitled drawing consists of six panels, that grow panel to panel, starting with a simple circle in gold situated within a delicately drawn geometric skeleton. It is part of her Caliphates series that stems from her training with illumination masters in Istanbul, analyzing and documenting the development of illumination styles over time. She builds the structure out one layer, and one panel at a time, adding to each set styles, symempires. The core is gold leaf, which is the ul- timate foundation of the art and it shines as the natural light from the gallery window cross- es its path as the design becomes more and more intricate with each iteration.

The final piece, Love is my Law, Love is my Faith is activated by the daylight, facing the pair of windows that illuminate the space. This work was originally debuted at the Kochi-Muziri’s biennial in 2016 and is comprised of eight hanging embroidered panels in off-white, open in the center, slowly burrowing to a perfect square of gold on the last, solid piece through concentric cuts along each piece. The light funnels through and makes the gold shimmer, literally illuminating the internal realm of the work.

This work was inspired by Ibn ‘Arabi’s love poems the Tâj al-Rasâ’il wa-Minhâj al-Wasâ’il, which are acknowledged as some of the most important love poems in the Arabic language. He was inspired while circling the Ka’ba and drinking the Zamzam water by the overwhelming presence of God, and the deep love that carried with it. He left the great mosque and immediately set to work, drafting eight individual poems. Each one is an effort to capture the many dimensions and manifestations of this love.

The layers of the piece come to stand for each of these written works, and each layer is hand embroidered with a different form related to sacred geometry. The embroidery mimics the circumambulation of the Ka’ba itself, continuously circling the core, referencing the community that gathers there and the connection that is forged between and through one another, and that between ones soul and a higher power.

The dialogue between the internal and external echoes throughout the exhibition. The layering and the fabric block the light, literally con- trasting the outer edges to the open center. The viewer circles the piece the embroidery almost melts away and the movement of the light dominates the experience as the panels are progressively surrounded in deepening shadows and the exposed form appears that much brighter. It is a meeting of the external light of the sun, and the internal light of the divine before returning again to the darkness of the installation room and then exiting.

Each piece is a conversation between the geometric traditions of the Islamic world and the contemporary world that we all navigate together. Almost miraculously, Awartani gives life to dialogues that span centuries while evoking unity. In finding her own voice, she allows the viewer to listen, and to be immersed. The title for the exhibition comes from a poem by Mahmood Darwish entitled It was night and she was lonely. It tells of two people dining alone, separated by “two empty tables” yet joined in that connective space and compan- ionship that allows strangers to feel familiar, and for the familiar to feel strange. “Nothing disturbs the silence between us,” Darwish writes. “Nothing of me disturbs her and noth- ing of her disturbs me, we’re in harmony with forgetfulness…” Awartani asks us to consider this harmony and what and whom we’re willing to let slip away for the sake of it.

Polishing The Mirror: The Artistic Journey of Dana Awartani

Contributing essay written by Professor Paul Marchant for the Artist’s solo show The Silence Between Us at Maraya Art Centre.

Dana Awartani’s outlook as an artist can be said to bring together the rigor and analysis of the intellect. She draws from ancient streams of classical philosophy and Islamic geometry through to the present, bridging international, traditional and contemporary perspectives of art, culture and spirituality. This cultivation of the heart-hand-mind, based on inner conviction, is an outwardly directed practice intended not to be removed from life, but to engage more deeply with it.

Awartani’s work is broad-ranging, multidimensional, and layered with symbolic meaning, building towards order and beauty in a world which often appears chaotic. This essay endeavours to outline some of the histories and techniques she employs in pursuit of this order and to provide insight into the systems which she continuously weaves together as she builds pieces.

The importance of Dana’s approach to her practice, regardless of the medium, is the relationship between highly refined systematic analysis, technical methodology, contemplation and deep empathy with her subjects. It enables her to discover the interrelatedness of all parts to accomplish whole compositions, whilst appreciating all the thresholds of their process of development. To achieve the discipline of both illumination and dimensional geometry that form the basis of her work, she studied with masters in Turkey and the UK, working towards obtaining the Ijaza in Istanbul (the highest award needed to practice and teach Islamic illumination) and at her Masters in traditional arts the Prince’s School of Traditional Arts with strong emphasis on geometry. This journey has provided her with not only an understanding of high level technical skills, but also of social organisation, cultural histories, philosophy, and spirituality. Her avowed aim is to revitalise traditional Islamic art forms through continual ritual acts of revival, renewal and performances of contemporaneity.

She carries this out as a true adept of authentic spontaneous expression, facilitating a way to view the world from a fresh perspective. The quality of spontaneity, in this case, is not about the unfettered expression of desires, but instead is a kind of trained spontaneous instinct that flows out of painstaking daily effort and repetition of learned, complex, disciplined skills. This spontaneous intuition makes further dimensions visible as she seeks to activate these traditional artistic processes and research as contemporary expressions.

The processes of geometric analysis and pattern construction are themselves a ritual using the two-legged compass and straight ruler. The word compass has the root compassus in Latin, which means ‘to step’ and is closely related to the word compassion. In a sense, the ritual act of making geometry is taking action towards contemplation of the compassionate reflection of Unity. The central message of the Holy Qur’an is the concept of Unity, al-Tawhid, and the awareness that there is no God but God. The aya (also meaning signs, symbols or similitudes) often refer to aspects of the natural world. Great importance is placed on their interpretation, as they are thought to be evidence of the power of God’s creation. They also remind man of his vital role as custodian of nature and vice-regent (khalifa) of God on earth. Again, according to the Holy Qur’an, the creation is connected to the properties of measure, symmetry and proportion: ‘Him Who created thee. Fashioned thee in due proportion, and gave thee a, just bias’, Qur’an 82.7.

In the process of obtaining the higher attributes of both the art of illumination and geometric composition, greater emphasis is placed on the understanding of proportional rectangles, shapes and figures related to the circle (the shape regarded by all traditions as the symbol of wholeness and perfection). When practising the continual renewal of traditional geometry, it is possible to experience a sense of one-ness through drawing geometric figures and harmonious patterns. As well as experiencing the interrelatedness of all phenomena in nature, one can begin to discern pattern and order in relation to cosmic rhythms that connect man to the universe.

Through daily effort and determined discipline, the deepening of one’s vision enables a pathway to experience a flow of creativity, that in turn, activates the spontaneity discussed earlier that makes a broader range of dimensions visible and the exploration of designs in the contemporary moment that reflect the depth of spiritual truths.

In the Islamic context the genius of pattern-making, art and craft by highly skilled artists is understood as the reflection of Divine Unity based on the laws underlying the universe. To the Muslim artist the Holy Qur’an affirms the power and mystery of God’s Creation and its connection to the properties of measure, symmetry and proportion: ‘Lo! We have created everything by measure’, Qur’an, 54.49.

In the desert that surrounded the Prophet Muhammad and his followers, the early Muslims made use of their enduring spirit for overcoming adversity in the harshest of natural environments to succeed in developing a unique sensitivity to nature. The ancient traditional science of navigation across the desert (developed from the time of the Ancient Egyptians) arose from observations of planets and constellations moving across the night sky. It was inspired by the wonder and awe of the vast heavenly firmament. The people of the desert also had a profound appreciation for the sparse crystalline structures of the sandy wilderness and open spaces, counterpoised by the fertility and variety of bio-life forms within the intimacy of the watery oasis. In Islamic art the two poles of crystalline and flowing forms are visualised as geometry and biomorphic design. They allude to the timeless quality of archetypes which have the potential to be renewed both in the present and future. In the words of S.H. Nasr “There is nothing more timely than the timeless.”

In his forward to Geometric Concepts of Islamic Art by Issam El-Said and Ayse Parman, Titus Burckhardt again identifies the circle as the source of all shapes and figures that are combined to make geometric patterns & designs and the underlying schema of flowing motifs:

‘Now the geometric models used in traditional art have nothing to do with the rational, or even rationalistic, systematisation of art; they derive from a geometry which is a priori non-quantitative and which itself is creative because it is linked to data inhering in the mind. At the basis of this geometry is the circle which is an image of the infinite whole and which, when evenly divided, gives rise to regularly shaped polygons which can, in their turn, be developed into star-shaped polygons elaborated indefinitely in perfectly harmonious proportions…’

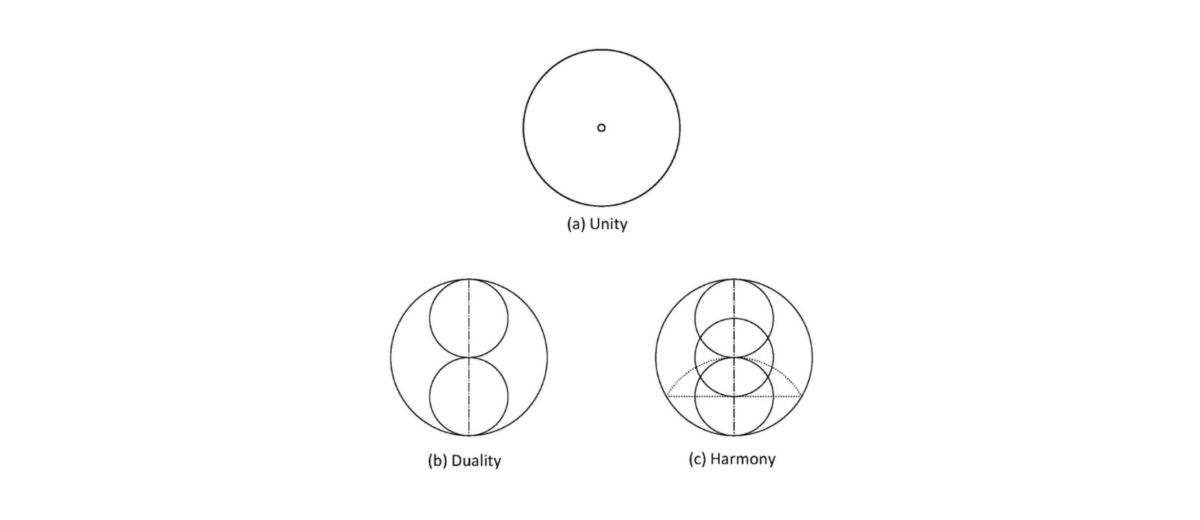

Dana Awartani’s geometric studies, the basis of all of her work, start and conclude with the circle, the primary symbolic shape. The circle can form the basis of any geometric shape and also with its repetition produce the pure linear symbolism of a plant motif in the formation of biomorphic designs. The Pythagorean sources corresponding to the genesis of Islamic pattern begins with the single circle – its centre, radius and circumference. A second circle of the same size can tangent the first, with both centres along a straight line. A third can be drawn with its centre on the point of contact between the first two. A fourth circle with a radius equal to the diameter of the other circles can be drawn with the same centre as the third circle to exactly meet the outer edges of the first two circles. This gives three diagrammatic possibilities: (a) the larger circle – Unity; (b) the larger circle containing two smaller circles touching – Duality; and (c) the larger circle containing all three smaller circles – Harmony (this drawing also depicts geometric construction details). What we have seen in this example of the Pythagorean paradigm based on the universal principles of pure Number and Form, is the emergence of Duality out of Unity, and the subsequent unification of duality, which in turn results in a dynamic, differentiated image of the One in three parts (see diagrams below)

This universal pattern underlies the Pythagorean view of the kosmos, literally ‘world order,’ a term that Pythagoras is credited with first applying to the universe. The word kosmos, in addition to its primary meaning (order), also means ornament and pertains to the universe being beautifully ordered. This can be said to have relation to art forms expressing the reflection of Unity in multiplicity or multiplicity in Unity.

These key fundamentals for the physical and philosophical base for all of Awartani’s practice but each series builds on, complicates, and enrichens the conversation and expression of these techniques, continuing centuries-old dialogues and blending them with the contemporary moment.

The Islamic Caliphates series demonstrate Awartani’s ability to undertake rigorous training to build the strength of her technical practice and through in depth exploration of the history of Islamic empires to give traditional Islamic illumination a platform in today’s world.

In this work, Awartani extends the range of her progressional drawings to achieve illuminations with a succession of elements demonstrating the contribution of each great civilization in the development of this art. It depicts the geographic and historical expansion of the religion; beginning at the centre with the birth of the religion in the Hejaz, signified by a gold circle, all the way to its apotheosis, spanning from the Far East to Europe, integrated in the completed ‘Shamsa’.

The progressional drawings in Awartani’s practice at large are foundational, show the progression and developmental growth of patterns as a key aspect in her approach to understanding the ‘synergy’ of pattern design. Synergy is defined as a ‘whole system’ unpredicted by any part or subset of parts. Her drawings originate with the circle and conclude in a circle as a compositional format, they work towards the completion of complex designs using her substantive knowledge of the vocabulary of symmetries and proportional systems. Although she can use the step by step approach of a series of drawings instructing the construction of a design, her drawings can also maintain a field of variations on a theme within different areas of the same composition. This indicates both the pathway towards understanding the complete system and also the insight to develop artistic expressions reflecting Divine Unity underlying the inexhaustible variety of the world of patterns.

In the Islamic Caliphates works, this process is complicated through research, incorporating six distinct styles that correlate with the expansive periods of the Islamic empires. Their presentation together become as a way to express essential universality translated through highly diverse elements that both make up the art of illumination and are a reflection of Islamic civilization as a whole. This again focuses on the concept of Unity, al-Tawhid, which can be interpreted as unity within multiplicity or multiplicity within unity, the core principle of Islam.

The Platonic Solid Duals Series: connects the technique of progressional drawings to the three-dimensional sculptures of the Platonic solids that were originally exhibited in the Marrakech Biennale in 2016.

Dana Awartani’s initial drawings investigate and explore the increasing complexity of designs within equilateral triangle and pentagonal formats inscribed within the circle. They also focus on the growth of pattern elements and their integration within the whole composition. The drawings develop in a sequential unfolding of pattern language, including five stages from circle to polygon, star, sub-grid and finally pattern. The drawings are rigorously analytical but also result in a kind of visual poetry with the variation of weight and quality of line. Some passages of the drawings remain at earlier stages of analysis; some are almost complete, demonstrating a thorough knowledge of symmetry, proportion, scale, harmony and counterpoint. The designs were made to cover the surfaces of the faces of the Platonic figures suspended within their larger ‘transparent’ duals, to complete each of the series of sculptures. The original three sculptures include: Dodecahedron within an Icosahedron, Octahedron within a Hexahedron (Cube) and Icosahedron within a Dodecahedron. These comprise four of the five Platonic solids, the Tetrahedron being omitted. In this exhibition, however all five of the forms are present for the first time.

Plato’s dialogue Timaeus, attributes the qualities of the elements in cosmogonic context as Tetrahedron (Fire), Octahedron (Air), Hexahedron also Cube (Earth), Icosahedron (Water) and Dodecagon (Heaven). Dana Awartani chose to use the material of wood for the internal solids, a substance that exemplifies the requirement of the first four elements to support life and that can also be symbolised as the ‘Tree of Life’.

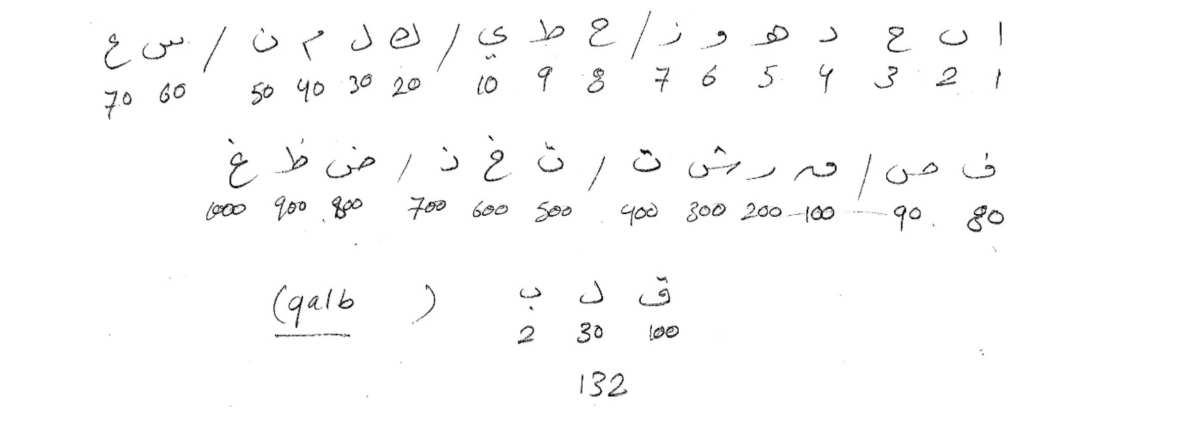

In the Abjad Hawaz series, exhibited along with the installation All (heavenly bodies) swim along, each in its orbit in the Yinchuan Biennale 2016; Dana Awartani returns to the theme that all things come from One and return to it, with significant interpretation of the tradition of Abjad. These are again exhibited together in this project at the Sharjah Art Museum, as part of the Sharjah Islamic Arts Festival’s larger exhibition.

Dana Awartani’s Abjad Hawaz series develops visual codes for the numbers connected to letters of the Arabic alphabet translated as illuminated geometric patterns and pattern groupings. They are at the same time inspired by the interest in the multi-layered symbolism of Sufi poetry, expressing the Sufi quest which reflects the return to Unity through the five states of being or ‘presences’ which are: the world of Divine Essence or ‘Ipseity’ (Hahut); the world of Divine Names and Qualities, or Universal Intellect, also identified as Pure Being (Lahut); the intelligible world, or world of angelic substances (Jabarut); the world of psychic and subtle manifestation(Malakut); and finally, the terrestrial domain, dominated by man (Nasut). Sometimes a sixth state of being is added – that of Universal Man (al-insan al-kamil).

The base of these works is Ilm-huruf, an ancient science that give the Arabic letters their numerical values to begin with. She builds upon the ancient numerical system, expansively divining an aesthetic language that revivifies the abjad and insists on its relevance. She is interested in the a co-dependency inherent in geometry where the form is the result of a numerical expression – without which geometry would not exist. Awartani abstracts and imparts pure meaning using this method to create a harmonious and formal expression of complex notions that are difficult to succinctly synthesise.

The Abjad Hawaz works are a pure study of this for each letter of the alphabet, six of which are present in this installation, and then All [heavenly bodies] swim along each in its orbit build on the same principles but complicate it, translating the drawing method into an installation. This piece is a study of one of the only palindromes in the Qur’an which gives the work its title and governs the formal execution.

Dana Awartani’s installation Love is my Law Love is my Faith, exhibited in the Kochi-Murzais Biennale in 2016, is inspired by eight love poems oby Sufi Muhyiddin Ibn ’Arabi, Considered by many to be the ‘greatest Master,’ he was a poet, philosopher and saint. He was inspired to write eight love poems after an inner experience while making tawaf (circumambulation around the Ka’aba seven times) and drinking the miraculous zamzam water during the Hajj pilgrimage to Mecca. The poems are described by the Ibn ’Arabi Society in the following way:

‘…the Tāj al-Rasā’il wa-Minhāj al-Wasā’il, The Crown of Epistles and the Path to Intercessions, in which Ibn ‘Arabi addresses eight love letters to the Ka’ba, contains all the variations that Arabic literature has to offer on the theme of love. This is an unusual love, for a being made of stone, but oh so sacred, situated in an intermediate world between the human and the divine. The following is only a first version, to make known a treatise, as rich as it is difficult, which must take its place beside the Tarjumān al-Ashwāq and the chapter on Love in the Futūhāt…’

The installation, Love is my Law Love is my Faith, is constructed as a succession of square borders receding in scale, the largest being at the front diminishing through to the smallest central square, seen within the depth of an overall suggestion of cubic space. The borders are each embroidered with intricate geometric roses and star patterns that give the effect of shimmering, sparkling light. The image form corresponds to the composition of a mandala (which is translated as ‘halo’ or ‘cluster of blessings’) – it is a contemplative image (also within the religious traditions of the sub-continent of India) which traditionally acts as a mirror allowing the viewer experience the reflection of ‘the spark of divine love’ within themselves, as an ‘in the moment’ experience of union with the rhythm of the universe. The viewer is not meant to immobilise himself at a point, enjoying the privilege of ‘present-ness’ and raise his eyes from this fixed point, he must raise himself toward each of the elements represented. Contemplation of the image becomes a mental itinerary, an inner accomplishment; the image performs the function of a mandala.

The installation is a multi-dimensional image that both resonates with unfathomably profound connection to the central spiritual truth of the Islamic faith, and also with the use of universal principles of geometric pattern. It draws together a common thread of dialogue between a range of cultures and spiritual traditions. The use of indigenous methods and materials linked to the past and present of Saudi tribal textiles, reflect on the conversation between the two, and results in finely embroidered borders that bring a profound significance to the particular cultural dimensions. The practical craft of the making process achieved at such a high level of refinement, is of itself an invocation towards the manifestation of an object for deep contemplation of divine Unity.

All credit must be given for the courage, conviction and contemporaneity of the performance of our artist Dana Awartani. Her beautiful and challenging works have established her as a highly capable international and intercultural practitioner. This is evinced by her geometric drawings, miniature painting, illumination, parquetry, ceramics, mosaics, stained glass, textiles, embroideries, sculptures and spatial installations. She communicates a strong determination to revive and renew traditional art relevant for today and is able to intercede between cultural and religious boundaries. Her aim appears to be the development of mutual respect and understanding, encouraging a better, more positive future for the world. She has dedicated herself to reaching the highest level of achievement in contemporary and traditional training during her formative education in the visual arts, in London and Istanbul. Dana produces work of rigour and discipline that is not only technically very accomplished, but through the daily ritual of sacred geometry and study of its philosophical and spiritual dimensions, is able to connect to the essential source and goes far beyond the ‘modern mentality’. It encourages us to regain our sense of true humanness and identity and that at the spiritual level, enables the recovery of both our symbolic sense and access to the Unity of Creation.

Works Consulted in approximate order of reference

Professor Michael Puett & Christine Gross-Loh, THE PATH, (Penguin 2016), ISBN: 978-0-241-97042-3. Titus Burckhardt, Sacred Art in East and West, (Perennial Books 1967), ISBN: 0-900588-11-X. Titus Burckhardt, ART OF ISLAM, Language and meaning, (WIFT 1973), and ISBN: 0-905035-00-3 M. Ali Lakhani, The Timeless Relevance of Traditional Wisdom, (World Wisdom 2010), ISBN: 978-1-935493-19-8. Issam El-Said, Geometric Concepts in Islamic Art, (WIFT 1976), ISBN: 0-905035-03-8 Kenneth Sylvian Guthrie, the Pythagorean Sourcebook and Library, (Phanes Press 1987), ISBN: 0-933999-50-X. Yusuf Ali (Trans), The Holy Qur’an, Islamic Propagation Centre International Albert Einstein – quote, H Eves, Mathematical Circles Adieu (Boston 1977). Plato, Philebus, Timaeus and Phaedrus, (Loeb Classical Library 1917-1990), ISBN: 0-674-99040-4. The Prince’s School of Traditional Arts, Arts & Crafts of the Islamic Lands, (Thames & Hudson 2013), ISBN: 978-0-500-51702-4. John Martineau, A Book of Coincidence, (Wooden Books 1995), ISBN 0-9525862-0-7. Nader Ardalan and Laleh Bakhtiar, the Sense of Unity, (University of Chicago Press 1973), ISBN0-226-02560-8. Professor Keith Critchlow, Islamic Patterns an Analytical and Cosmological Approach, (Thames and Hudson 1976), ISBN: 0-500-27071-6. Seyyed Hossein Nasr, Science & Civilization in Islam (Islamic Texts Society1987), ISBN: 0-946621-11-X. W.S. Andrews, Magic Squares & Cubes, (Dover 1960). Seyyed Hossein Nasr, An introduction the Cosmological Doctrines, (Thames & Hudson 1978), ISBN: 0-500-27216-6. Daisaku Ikeda & Majid Tehranian, GLOBAL CIVILZATION, A Buddhist – Islamic Dialogue, (British Academic Press 2003), ISBN: 0-946621-11-X. Maria Rosa Menocal, The Ornament of the World, (Back Bay Books 2002), ISBN: 978-0-316-56688-9. Titus Burckhardt, Mystical Astrology According to Ibn ’Arabi, (Beshara Press 1977), ISBN: 0-904975-09-6 René Guénon, The Great Triad, (Quinta Essentia 1991), ISBN: 1-870196-06-6 Titus Burckhardt, The Mirror of the Intellect,(Quinta Essentia 1987), ISBN: 0-946621-08-X René Guénon, Fundamental Symbols, The Universal Language of Sacred Science, (Quinta Essentia 1995), ISBN1: 1-870196-10-4.

Detroit Affinities: Dana Awartani

Curatorial essay written by Jens Hoffman for the Artist”s solo show at the Museum of Contemporary Art Detroit.

For Dana Awartani, a half-Palestinian, half-Saudi artist who lives and works in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, geometric patterns express both the rational and the spiritual parts of us. Using mathematical principles, numerically devised symbols, and traditional Islamic patterning, Awartani creates paintings, installation sculptures, performances, and textile works that are as rich with meaning as they are beautiful, elegant, and precise. Awartani situates her artistic practice at the juncture between tradition and the now. Though her forms, methodologies, and interests are largely rooted in the study and understanding of traditional Islamic forms, Awartani is also keenly interested in the translation, translocation, and transformation of these forms into our contemporary, global world.

Though the forms explored in Awartani’s artworks are derived from Islamic traditions, part of her interest in these geometries is that they are also universal. Borrowed from and reflected in nature, present in the religious iconographies of many global religions, and reliant upon the rules of mathematics, Awartani’s geometric patterns can be interpreted and appreciated through many different lenses. Striking a careful balance between the conceptual and the technical elements of art practice—Awartani pursued both conventional contemporary fine art as well as traditional arts as a student in London—, Awartani creates hypnotic visual stories that exist in that rich territory between abstraction and representation.

In Awartani’s visual world, the curve of a line or the number of points on a star convey specific meanings. Her paintings and installations echo traditional Islamic artworks, which use complex geometric patterns to symbolize the Divine. In the traditional artworks that she aims to revive for our contemporary era, each color, line, shape, and flourish is part of a story; in Awartani’s works, this symbolism remains and is expanded through her own innovations. While so much of her practice focuses on revitalizing the neglected methods of traditional Islamic art, Awartani is not content to replicate the ancient in the present. Her works consider issues relevant to our contemporary moment—like gender, religion, faith, and loss— speaking of the present through the visual language of the past.